St Kilda evacuation to be marked

- Published

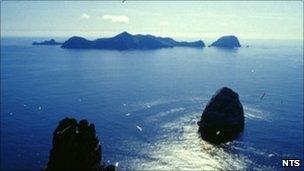

The archipelago was evacuated after life for islanders became too difficult

The 80th anniversary of the evacuation of St Kilda is to be marked by a series of events.

The last islanders left on 29 August 1930 because life on the remote archipelago had become too difficult.

Speakers at a conference held by the Western Isles-based Islands Book Trust will include John MacDonald, whose father Calum was among the evacuees.

An exhibition of paintings that feature St Kilda will also be held at Taigh Chearsabhagh Museum and Gallery.

The National Trust for Scotland (NTS), which manages the islands, is supporting the events.

Other speakers at the conference include David Boddington, who spent time on St Kilda while serving as an Army medical officer.

He will also launch his book St Kilda Diary - A Record of the Early Re-Occupation of St Kilda.

Genealogist Bill Lawson is another of the guests at the event which will be held on Benbecula from 11-14 August.

The display of paintings by Dutch artist Fred Schley will run at Taigh Chearsabhagh in Lochmaddy, North Uist, until 28 August.

People had lived on St Kilda, the westernmost islands of the Outer Hebrides, since prehistoric times.

In the 19th Century, tourists began to visit the archipelago and the St Kildans - known as the Hiortaich - became more dependent on the outside world.

In the 1850s, 42 of the islanders emigrated to Australia, half of them dying on the way.

Until that decade ended, their houses had been built from materials that were easily available on the largest island, Hirta, with stone walls and roofs of thatch or turf.

Contact with the mainland led to the building of 16 new houses on Hirta in the 1860s.

These new homes were cold, and it was necessary to import coal from the mainland as the supplies of peat on St Kilda were not sufficient to heat them.

Islanders' ankles

The development of tourism meant the world learned of the St Kilda Parliament, in which the men met each morning to discuss the day's tasks.

Visitors reported that the islanders' ankles were unusually thick and strong from climbing cliffs to hunt seabirds, which were the basis of their economy.

The contact with non-islanders has been blamed for increasing disease and high rates of infant mortality.

The winter of 1929 was particularly hard on the island and some of the remaining inhabitants died, many having already left.

The remaining 36 islanders wrote to the government asking to be taken off so they could lead new lives on the mainland. The island was abandoned the following year.

- Published12 July 2010