Scotland's role in moulding America's first black combat pilot

- Published

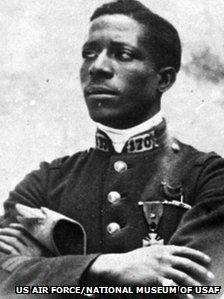

Eugene Bullard served as a soldier before becoming a pilot

Red Tails opens in cinemas on Wednesday. Inspired by real events, the film tells of an all-black US squadron overcoming prejudice at home to fight on the front line. But they were not the first African Americans to fly in combat. Eugene Bullard flew with the French in World War One - after first fleeing the US to Scotland.

As a boy Eugene Jacques Bullard saw little of the American dream.

His mother died when he was five and his father was almost lynched a few years later.

Georgia-born Bullard's ancestors included slaves from Martinique who were brought to America by their French owners as they fled the Haitian slave revolution.

His father spoke French and also talked fondly of France, instilling in Bullard a belief that it was the true land of opportunity, free of prejudice.

Spurred by the attempt to lynch his father and his own brushes with racial hatred, Bullard worked towards getting himself to Paris.

But his journey would first take him to Aberdeen and Glasgow.

According to Craig Lloyd's book Eugene Bullard: Black Expatriate in Jazz-Age Paris, Bullard was barely in his teens when he stowed away on a German cargo ship at Norfolk, Virginia.

The captain of the Marta Russ first threatened to throw Bullard overboard, before giving him the chance of working on the ship on its passage to Aberdeen.

The journey would have taken him through the Pentland Firth, the stretch of water between the Caithness coast and Orkney.

On reaching the Granite City, Bullard was taken ashore in a rowing boat to avoid any complications with the port authorities.

Aberdeen was at that time a busy fishing port with trams clanking up and down its streets.

Lloyd said the young American spent a day in the city before taking a train to Glasgow.

While Bullard was relieved to find he was not the target of vicious racial abuse in Scotland, Lloyd said that he did have one immediate problem.

Lloyd wrote: "At first he had difficulty with the Scottish dialect and accent: 'the language the natives spoke was sort of like English'."

In north-east Scotland, Bullard was likely to have encountered Doric, or Scots, before finding the accent changing as he travelled south.

Once in Glasgow, he quickly made friends with young Scots who helped him to find accommodation and food.

The Somme

Bullard spent five months in Glasgow and earned money acting as a lookout at illegal gambling dens.

Lloyd said there were occasions in Scotland when Bullard found himself described in offensive terms, but he did not encounter the same level of "racial taunt or rebuke" as he had done in America.

The author quotes Bullard as saying: "Within 24 hours I was born into a new world."

From Glasgow, he went to Liverpool where he worked at its docks and trained as a boxer, before finally realising his dream of settling in France.

In World War I, he served with the French Foreign Legion and saw action at some of the bloodiest battles, including the Somme and Artois Ridge.

Wounds he suffered at Verdun ruled him out from returning to the front line as a soldier, but he was offered a chance to become a pilot with the French Flying Corps.

In 1917, he qualified as a flyer. He earned one officially confirmed kill.

When the US entered the war, Bullard sought a transfer to its air force.

In his paper Corporal Eugene Jacques Bullard: First Black American Pilot, historian William Chivalette wrote: "As a pilot and an American he was invited to transfer to the American Air Force with the promise of being promoted.

"After passing the physical, when many other American pilots departed to fight with fellow Americans, Bullard's application was ignored for the duration of the war."

Bullard remained in Paris after the war.

He became part-owner of a night club, got married and had three children.

During World War II, he fought with the French resistance until he was badly wounded and was smuggled into Spain.

Mr Chivalette, curator at the Air Force Enlisted Heritage Research Institute in Alabama, said France recognised Bullard's heroics.

But he added that "perhaps through disinterest or uncaring", the US failed to honour Bullard until 33 years after his death when the US Air Force posthumously commissioned him as a lieutenant.

Finally, Bullard was regarded as an all-American hero.