Shark liver oil: When Scots hunted big sharks

- Published

Basking sharks feed on plankton by opening their maws wide

A project tagging basking sharks that gather in Scottish waters is to be extended. But in the past the sharks were not sought out by scientists but by hunters eager to harvest their prized livers.

Basking sharks are true monsters of the deep.

They are the world's second biggest fish - the whale shark is the largest - and can grow to 11m (36ft) and weigh up to seven tonnes.

Basking sharks have no teeth and feed on microscopic plankton by opening wide their huge mouths.

Every summer the sharks gather in large numbers around small islands off Scotland's west coast where they are sought out by scientists and wildlife watchers.

But until 1994 they were hunted with harpoons for the oil in their livers.

According to a 1917 volume of The Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, a basking shark liver is "very heavy, often weighing as much as one tonne" and yields a "pale yellow to orange yellow" oil.

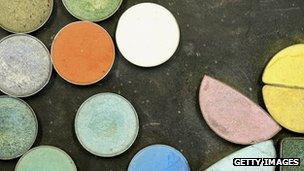

Cosmetics used shark liver oil before other materials became available

A single liver can provide 200 to 400 gallons of this liquid, according to the Canadian Shark Research Laboratory.

In the 18th and 19th centuries the oil was used to fuel lamps before it was replaced by petroleum. Other uses, however, were found for the shark liver oil.

The oil contains squalene, a property that helped in the manufacture of industrial lubricants and, at the other end of the scale, cosmetics, perfume and artificial silk.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature said as well as the liver oil, the sharks were caught for their skin for leather and for making fishmeal to feed to livestock.

Most of the oil landed in the UK in the 1980s and 1990s was exported to Norway, according the Marine Conservation Society.

However, the rise of synthetic materials in the 20th Century made UK fisheries less profitable. The value of the livers fell from £550 per tonne in the 1970s to about £250 by the early 1990s.

'Shark invasion'

Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH), which is involved in the tagging project, said hunting reached a peak in 1947 when 250 sharks were landed. More than 100 were landed in the 1980s.

Across the whole of the North East Atlantic, there was a record 4,500 basking sharks caught in 1960.

Gavin Maxwell's shark fishing station

Among the shark fishermen pushing the hunting to those peaks was Peterhead-born Joseph "Tex" Geddes.

The former soldier began hunting for basking sharks after the end of World War II.

Geddes and a fellow fishermen hunted in the Minch in a boat smaller than some of the sharks they harpooned.

For a time he worked with Gavin Maxwell, who became famous for his conservation work and books about otters.

However, Maxwell's attempt to run a shark fishing station as business venture on Soay, an island off Skye, failed.

Geddes, who died in 1998, wrote about his shark fishing adventures in his 1960 book, Hebridean Sharker. It has since been republished.

In the book, he told of harpooning large sharks and then being towed by the startled fish at speeds greater than his boat could achieve under its own power.

His vessel was badly damaged in one encounter with another big shark as it thrashed around after being harpooned.

Geddes also recalled how a Norwegian crew, drawn to Scottish waters by a newspaper report of a "shark invasion", praised his method for harvesting livers.

The fisherman wrote: "That season for greater speed we had hitherto made it a practice, when in deep water, to cut the liver clear of the shark first, when it would float astern of the boat, and get rid of the shark at once before circling round and brailing the liver aboard."

Geddes said the Norwegians' method involved a fiddly task of fishing out the liver using a net and poles.

SNH is cautious about whether declining numbers of the animals have increased since the end of shark hunting off Scotland.

Last summer, shoals of 73 fish were counted off Coll and a shoal of 50 was recorded around Hyskeir, a group of rocky islets near Canna.

An SNH spokeswoman said of possible signs of recovery: "It's very difficult to gauge as there's not enough information to undertake population estimates.

"However, one of the reasons shark hunting decreased was due to difficulty in finding shoals of sharks, plus other sources of oil became available.

"Recent surface sightings of larger sharks and smaller juvenile sharks is promising, as are the recent large numbers of surface sightings around Tiree."

- Published13 March 2013