The Crofters' War and the Napier Commission

- Published

Marines landed at Meanish Pier at Glendale on Skye as part of an effort to control islanders who had rioted over land rights

The Napier Commission began gathering evidence across the Highlands and Islands 130 years ago this month. But what was the commission and did it achieve its aims?

In early 1883, the iron-hulled gunboat Jackal dropped anchor in the sheltered waters of a sea loch in Skye.

The appearance of the Royal Navy in Loch Pooltiel, off Glendale, signalled an escalation in what was known as the Crofters' War.

Waged over large parts of the 1800s, the "war" was a dispute between landowners and communities distressed by high rents, their lack of rights to land, or facing eviction to make way for large-scale farming operations.

The process of moving families out of inland areas where they had raised cattle for generations to coastal fringes of large estates, or abroad to territories in Canada, had started with the Highland Clearances in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Both the clearances and the Crofters' War were marked by violent clashes between people facing eviction and landowners and the authorities.

Going barefoot

One of the bloodiest incidents was the Battle of the Braes on Skye in 1882. After being attacked with stones by a crowd of men and women, about 50 police officers from Glasgow baton-charged the mob.

The unrest spread to Glendale and in 1883 the frustrated authorities called for military intervention to help round up the ring-leaders.

Marines disembarked the Jackal and landed at Glendale's Meanish Pier and assisted police in making arrests.

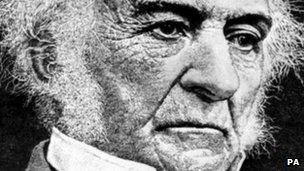

But the agitation continued and Prime Minister William Gladstone ordered a public inquiry, something that had been called for before but rejected by the government.

Backed by Royal approval, the Napier Commission was set up. It was led by Francis Napier, a respected diplomat and the 10th Lord Napier.

Prime Minister William Gladstone hoped the commission would end the unrest

In May 1883, it began gathering evidence at hearings across the Highlands and Islands.

Dr Elizabeth Ritchie, a lecturer in Scottish history at the University of the Highlands and Islands, said granting an inquiry was a major concession to land reformers and crofters from the government.

"Gladstone hoped that the news of the commission would help quell disturbances," she said.

"The commission itself was welcomed by crofters, and greeted with a mix of suspicion and anger by estate management."

Estate bosses and landowners were outraged and felt that the government was interfering in private property.

All sides, however, sought to present strong cases to the commission.

Dr Annie Tindley, in her book The Sutherland Estate, 1850-1920: aristocratic decline, estate management and land reform, tells of estate managers steering the commission panel towards visits to prosperous areas of Sutherland rather than the poorer ones.

The Highland Land Law Reform Association was also well organised, according to Allan McColl's book Land, Faith and the Crofting Community. Two of its leaders toured the Highlands in an effort to help as many crofters as possible prepare their evidence.

Crofters told the hearings of being denied land on which they could grow crops and graze livestock.

Landowners and estate factors defended their actions and insisted change was needed to improve the agricultural output of estates.

The commission also heard evidence of sickness and diseases that afflicted crofting families, and of women and children going barefoot in rain and snow.

Dr Ritchie believes there were various reasons behind the health problems.

She said likely factors behind the bad health included families living in overcrowded "rural slums" on the fringes of estates where it was hard for them to grow sufficient food.

People lived in damp, smoky thatched homes, conditions which encouraged the spread of eye and respiratory diseases. But Dr Ritchie said homes were deliberately made smoky because a sooty thatch, when it was replaced, could be used as a fertiliser.

Introduced golf

In 1884, the commission published its report and it was criticised by all involved. Rather than open the way for new legislation, it indicated that the government preferred that landowners and crofters worked out their differences without the weight of law.

Golf playing marines were sent to Tiree in 1886 to tackle locals who had risen up against their landlord

The following year crofters put up six candidates in a General Election, the first to be held after voting reform.

One of the candidates stood against the Duke of Sutherland and, while the crofters' man lost, it was a move that played a part in eroding the Sutherland estate's political influence.

The Crofters' Party did manage to get five of its candidates elected.

In 1886 the Crofters Holdings (Scotland) Act was passed. However, this legislation did not solve all the problems over land rights and disputes continued into the years between the two world wars in the 20th century.

The year 1886 also saw another dispute over land rights that led to military involvement.

In August, 250 marines landed on Tiree from ironclad warship HMS Ajax and troop ship HMS Assistance.

At first they got a hostile reception from locals, who had been calling for an area of the island to be broken up into crofts, but the marines won them over by helping to take in the harvest.

Col Mackay Heriot, the officer in charge, and nine officers also introduced golf to the island. They played among the machair and stirred islanders into having a proper course laid out.

Dr Ritchie said the Napier Commission should not be regarded as a complete failure.

She said: "Despite nobody being satisfied with the report and it never becoming the basis for legislation, it had a profound influence on how the land reform movement in the Highlands developed.

"It helped to politicise and organise crofters, who took national and local opportunities to push demands for land reform."

Dr Ritchie added: "It put estates into the public eye so they could no longer act with impunity, and it opened the way for government to get involved in matters which had previously been seen as issues of private property."

And what of Meanish Pier where marines landed 130 years ago to quell restless crofters?

In 2012, community group the Glendale Trust revealed a plan to buy the pier from the owner, Highland Council.

The trust said it hoped to upgrade the run-down pier and make it available to visitors armed with guide books, rather than guns.

- Published20 September 2012

- Published15 May 2012

- Published9 November 2011