The Honeyballers: Women who fought to play football

- Published

A Scotland Ladies Team of the past

Women's football is flourishing, but for centuries the game endured chronic discrimination, sexism and was even banned.

Britain's first recorded international women's football match was played in Edinburgh in May 1881.

A team representing Scotland beat one from England 3-0, with Lily St Clair scoring the opener.

In a report following the match, the Glasgow Herald described the Scottish team as looking smart in blue jerseys, white knickerbockers, red belts and high heeled boots.

Another game followed a few days later, this time in Glasgow.

It had to be abandoned when hundreds of men ran on to the pitch. The players escaped on a bus drawn by four grey horses amid chaotic scenes of vandalism and fighting between spectators and police.

There were grumblings in Victorian society. "Novelty" women's matches had no place in a "man's game", it was suggested.

In 1894, medical professionals called for girls and women to be banned completely from playing.

However, some determined characters refused to be denied a sport that they were passionate about.

The British Ladies Football Club was formed in 1895 with Dumfries aristocrat Lady Florence Dixie as its patron. Team captain was Mary Hutson who played under the pseudonym, Nettie Honeyball.

Hutson's adopted name was the inspiration for the title of BBC Alba's new documentary, Honeyballers, which will be shown on the Gaelic TV channel following live coverage of Scotland Women's World Cup 2015 qualifier against Bosnia-Herzegovina.

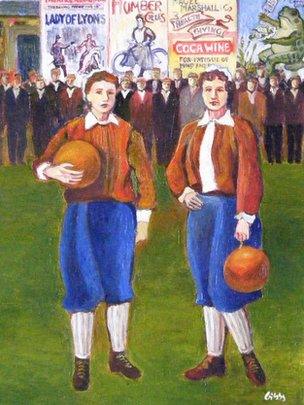

A painting by Glasgow artist Stuart Gibbs of players in 1895's British Ladies Team

The programme charts the difficulties Scotland's women's football pioneers faced, and also features interviews with some of those playing at the top level today.

Richard McBrearty, curator of the Scottish Football Museum, tells the documentary that in the past Scottish football's governing body actively discouraged women from taking part.

"You just have to look at the Scottish FA in the 19th Century. It's a men-only club," he said.

"The prospect of women playing football to them is incredulous. They shouldn't be doing it, full stop. They don't want to have a conversation about it.

"The simple fact is that it's a men-only game. They refer to it as a masculine game."

He added: "On top of that, you have a sports press who totally and utterly agree with that philosophy on sport and football in particular, that women shouldn't be playing it."

National scandal

The British Ladies Football Club sought to change attitudes.

Dr Jean Williams, a senior research fellow at De Montford University, said: "One of the really interesting things about the British Ladies Football Club is the way in which the middle class Nettie Honeyball, who is secretary of the club, cooperated with the aristocrat Lady Florence Dixie.

"Lady Florence Dixie was significant, although we don't think she ever kicked a ball in her life, because she as an incredible sportswoman.

"She was very much into hunting, shooting and fishing, and she was very much an explorer."

A re-enactment of 1895's British Ladies Team training in Honeyballers

But the aristocrat also attracted controversy because her brother, the Marquis of Queensberry, was wrapped up in a national scandal.

In 1895, the marquis was sued for libel by Oscar Wilde after he accused the novelist and playwright of being homosexual.

Wilde, who had earlier begun an affair with Queensberry's son, Alfred, lost the legal case.

Dr Williams said: "Anything that Lady Florence Dixie did in 1895 was going to be slightly scandalous, therefore her connection with women's football gave it a currency with press and the media that it wouldn't otherwise have had."

In 1902, there was a renewed effort to stamp out the women's game when the Council of the Football Association issued a warning to its member clubs not to allow charitable matches against women's teams to be played.

Later, during World War I, there was a brief revival.

With thousands of men sent away to fight in the trenches, women took up traditional male roles in work and play.

Dr Fiona Skillen, of Glasgow Caledonian University, said: "The First World War is a real critical point for women, especially working class women.

"The First World War opens up a number of opportunities as women are needed to go into the workplace to take up the jobs that the men have left vacant and so, you find that there is a growth in different kinds of sports, different kinds of leisure activities, because these young women are getting involved with them."

New teams emerged including one from Beardmore's Forge in Parkhead, Glasgow, that played an unofficial match against an English side at Celtic Park on 2 March 1918.

Crowds of more than 50,000 turned out to watch games, but the end of the war was soon followed by an official British ban on the women's game in 1921.

Museum curator Mr McBrearty said the game was again driven underground.

He said: "If you look through the Scottish FA minute books, from 1924/1925, there's three separate clubs - Raith Rovers, Aberdeen, and Queen of the South - who make approaches to the Scottish FA requesting permission for their grounds to be used for women's football matches.

"And, in each occasion the Scottish FA, quite damningly, tells them 'no', that you cannot use your grounds for staging these particular matches."

But the women's game survived thanks to the determination of teams both north and south of the border.

'Radical changes'

World War II initially saw strict limits in Britain on football matches. The rules were later relaxed and allowed the holding of games that did not pose a risk to the country's fighting ability, and had restricted crowd numbers so the grounds could be easily evacuated in the event of an air raid.

Women also played and there are records from 1943 of a team of electrical engineers, calling themselves Bright Sparks, taking on a munitions workers' side dubbed Great Guns.

After the war women were still playing and the teams included Edinburgh Dynamos.

Eventually the ban was officially lifted in the 1970s. But some age-old problems persisted.

An Edinburgh Dynamos team in 1946

Mr McBrearty said: "You look back to the 1970s and you would expect to see radical changes to attitudes to sport and society, in general.

"However, looking at the information from research, attitudes haven't changed remarkably from the 19th Century, up as far as the early 1970s.

"There still is, largely, a male dominated authority, and the press have to put their hands up to the fact that, again, it's a male dominated press who don't really actively look at the women's game favourably."

Big names

The game has changed much since the 1970s, with some games now being shown live on TV, including a number of matches from the Scotland national side's current World Cup campaign.

Arsenal Ladies player Kim Little is among today's Scotland internationals

Scotland, England, Wales and Northern Ireland have officially recognised international teams and league set ups.

Scottish league teams include Aberdeen, Glasgow City and Kilwinning and national team players include Kim Little, Jennifer Beattie and Gemma Fay.

England's big names include Eniola Aluko, whose brother Sone played for Aberdeen and now stars for Hull.

In Wales, the sport has seen a huge growth in popularity.

The Welsh Football Trust has 4,000 registered female players playing within the eight junior and five senior league structures, making it the largest participation sport for girls in Wales.

Honeyballers will be broadcast on BBC Alba on Thursday at 21:30 following live coverage of Scotland Women's World Cup 2015 qualifier against Bosnia-Herzegovina.

- Published3 September 2013