Super infuriating animals? The business of tackling unwelcome animals

- Published

Hedgehogs have been targeted on the Western Isles after being blamed for feeding on wild birds' eggs

A project to eradicate black rats from a group of small uninhabited Scottish islands secured European Union funding this month.

The Shiant Seabird Recovery Project is not the first scheme to secure thousands of pounds to tackle unwelcome non-native species.

But how did these creatures get to some of the furthest flung corners of Scotland, why are they a pest and what is the price of dealing with them?

Meet what conservation charities and government agencies might consider to be Scotland's super infuriating animals.

The Shiant Islands has an issue with the descendants of shipwreck survivors

Where?: The Shiants are a group of three small, uninhabited islands in the Minch. The isles between Lewis and Skye have been owned by the same family for three generations.

It is not clear at this stage how many rats are on the Shiants

What is the threat?: Black rats, also known as the ships' rat.

The Shiants' population is descended from rats that swam ashore from shipwrecked boats in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

What is at risk?: Today, unknown numbers of the rats prey on the eggs and young of ground-nesting seabirds.

The islands support 10% of the UK's puffin population and are home to 7% of the UK's razorbills. It has been estimated that there are more than 150,000 seabirds on the Shiants.

Solution?: Poisoned bait has been assessed to be the most effective way of dealing with the rats and will start being laid in the near future.

Cost?: The Shiant Seabird Recovery Project is a partnership between RSPB Scotland, Scottish Natural Heritage and the Nicolson family, the islands' owners.

The rat eradication project will cost about £900,000 - Scottish Natural Heritage is providing £200,000 and the remainder will be raised from donations.

In the past, Canna's residents have had to call on the help of pest controllers to deal with rats

Where?: Canna, the most westerly of the Small Isles of the Inner Hebrides.

What is the threat?: Rabbits. Last year, National Trust for Scotland (NTS), which owns the island, estimated there were more than 16,000 rabbits on Canna.

Some of Canna's rabbits were spared as they are prey for eagles

What is at risk?: The burrowing animals were blamed for causing a landslide that affected a main road on the isle in 2013. Rabbit digging has also damaged archaeological sites.

Solution?: A combination of trapping and shooting was done between January and March this year.

However, not all the rabbits were killed because they are source of food for eagles that nest on the island.

Canna previously had a problem with rats. Work to exterminate the animals was completed in 2008.

The animals were eating the eggs and chicks of ground-nesting seabirds, seriously affecting their population.

Pest controllers from New Zealand were brought in to deal with thousands of rats, using poison and traps.

The rodents first arrived on the island on ships about 100 years ago.

They had also posed a threat to Canna's rare wood mice, 130 of which were transferred to Edinburgh Zoo before the cull.

Cost?: The rabbit control measures cost NTS more than £5,000.

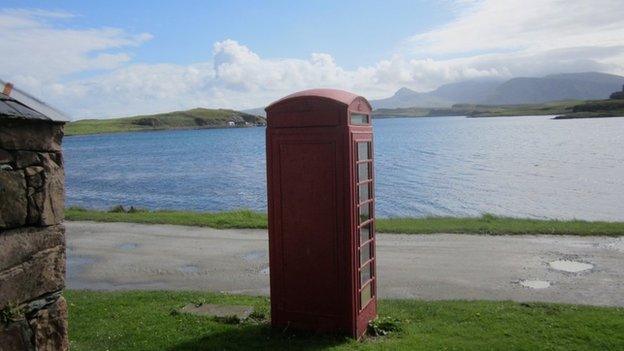

Harris is one of the islands where mink have been targeted

Where?: The Western Isles, including Harris and the Uists.

What is the threat?: American mink. The mammals became established in the wild in Britain in the 1950s following numerous escapes and releases from fur farms.

American mink escaped into the wild from fur farms

What is at risk?: Described as an "aggressive predator" by SNH, mink prey on ground-nesting and migratory birds.

In 2010, the animals were blamed for almost wiping out ground-nesting birds on Sandaig and the Sound of Sleat on Skye.

Solution?: The Hebridean Mink Project was started in 2001 and involves the trapping and killing of the animals.

Since 2007, 1,648 mink have been captured. Seven have been trapped so far this year.

SNH said the project is now in a two-year monitoring phase to locate and control the last mink.

Today's traps have technology that sends out a text alert to the project team when something is caught.

Cost?: Almost £4.5m from 1 April 2001 to 31 March 2014.

SNH has contributed more than £3m towards the cost.

Another £1.4m came from other organisations, including £785,557 from a European Commission conservation projects fund, £230,198 from Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, £150,000 from the former Scottish Executive, £103,039 from Highlands and Islands Enterprise, £97,198 from the Outer Hebrides Fisheries Trust, £42,611 from RSPB Scotland and £42,379 from the Central Science Library.

Where?: The Uists in the Western Isles.

What is the threat?: Hedgehogs. The prickly creatures are not native to the Western Isles, but in 1974 seven were introduced to Daliburgh in South Uist to eat slugs.

Hedgehogs arrived on South Uist in the 1970s

By 1995 hedgehogs were common throughout South Uist and Benbecula, their numbers growing in part thanks to the lack of predators and not being run down on the isles' quiet roads.

What is at risk?: The hedgehogs eat the eggs of ground-nesting birds. From the 1970s, the numbers of the animals grew to several thousand.

In terms of the birds, research in 1983 suggested that were 17,000 pairs of waders, including 25% of the total UK breeding populations of both dunlin and ringed plover.

A repeat of the study in 1995 recorded a 64% decline in dunlins, 57% fall in ringed plover, 43% fewer snipe and a 40% reduction in redshank in South Uist and Benbecula. Hedgehogs were assessed to be the top cause for the declines.

Solution?: The Uist Wader Project was launched in 2001.

First hedgehogs were culled, but this was soon stopped and the Uist Hedgehog Rescue (UHR) was launched and started receiving funding to trap and relocate the animals to the Scottish mainland.

Since 2002, UHR has moved about 1,600 hedgehogs.

This year the main focus of the project is further research on predation on birds' nests.

So far in 2014, 28 hedgehogs have been removed from an RSPB reserve at Balranald, and another 75 from a trial removal in "a high density" 2 km area of South Uist.

Cost?: Total cost from 1 April 2001 to 31 March 2014 of £2.1m.

This figure includes a contribution of more than £1.9m from SNH, £97,870 from RSPB Scotland and £20,000 from the former Scottish Executive.

Non-native species also have an economic impact with farming and forestry having the biggest annual cost, according to SNH.

The animals causing the harm include rats, rabbits, sika deer and worm-like nematodes that can damage potato crops.

In freshwater, American signal crayfish prey, which prey on young fish, and invasive Japanese knotweed that chokes out other plant life are estimated to cost the Scottish economy about £244m each year because of the damage they cause to angling and habitats.