Toxic conundrum: Dealing with Dounreay's leftovers

- Published

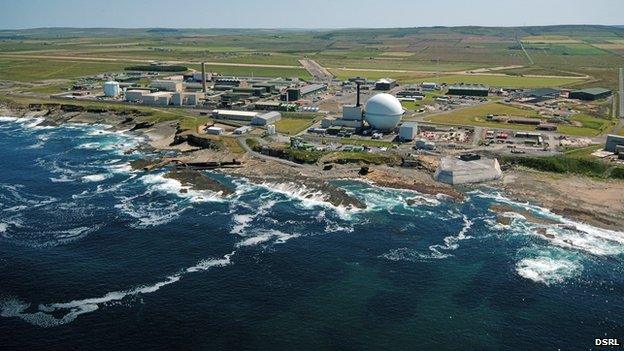

Built in the 1950s to push forward the UK's nuclear energy ambitions, Dounreay is now at the centre of complex £1.6bn demolition job.

The incident which saw cargo ship Parida drifting in the Moray Firth has, and not for the first time, cast a spotlight on the issue of dealing with part of Dounreay's legacy - its tonnes of radioactive waste, nuclear fuel and other contaminated material.

So how are these toxic leftovers being handled, and what kinds of material are involved?

Foreign material

The MV Parida was taking waste to Belgium

During the 1990s, nuclear material was sent from abroad to Dounreay for reprocessing.

The customers included power plants and research centres in Australia, Germany and Belgium.

In October 1991, three protestors sought to prevent spent fuel rods from Germany from reaching Dounreay by road.

The demonstrators lay on the carriageway of the Kessock Bridge near Inverness. Police moved the protestors and the convoy continued its journey north.

Because Dounreay is being decommissioned, the foreign material is now being sent back to the countries from which it originated.

In 2011, it was announced that more than 150 tonnes of intermediate level waste would be transported back to Belgium in 21 shipments over four years.

The waste was the result of reprocessing 240 spent fuel elements from Belgium's BR2 research reactor, which produces isotopes for use in medicine and industry.

The reprocessing created about 22,680 litres of liquid waste. This has been mixed with cement and poured into 123 drums each weighing 1.25 tonnes.

Danish company Poulsens has been contracted by the Belgian authorities to take the drums to Belgium. The first shipment left Scotland in September 2012.

The MV Parida, the Turkish-built ship involved in Tuesday night's incident, was designed and constructed to handle specialist cargo.

It structure has been strengthened so it can carry heavy, dangerous goods.

The vessel was making the 19th of the 21 shipments of waste from Dounreay.

Dounreay Site Restoration Limited (DSRL) said it does not allow any material to leave its site unless it was "fully satisfied" the carrier complied with "stringent safety and security" regulations.

DSRL added: "In almost 60 years of nuclear transports from the site, there has never been a release of radioactivity.

"We are determined to keep that record intact."

The vaults

One of the two vaults where low-level radioactive material will be stored

Dounreay's two experimental reactors - the Dounreay Fast Reactor (DFR), which is housed under the plant's landmark white dome, and the Prototype Fast Reactor (PFR) - are among the facilities which are being cleaned up and dismantled.

However, some new structures are also appearing on the site.

They include the first of two massive vaults where low-level radioactive material will be stored. The facility is costing about £20m to construct.

Each vault will be able to hold the equivalent of between 370 and 450 double decker buses.

The floor of the first vault is 36ft (11m) below ground and the construction work involved 260 tonnes of steel.

The land where the vaults are located will remain a restricted area for 300 years after the decommissioning of Dounreay is completed in 2025 because of the radioactive material stored inside the facilities.

Breeder and exotics

While low-level radioactive material will be stored at Dounreay, it has been deemed to be too expensive to handle other products on-site.

Breeder is classed by the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA) as a material which was was used in the process of generating nuclear power, but is not fuel or waste.

It comes in the form of cylinders of uranium metal, about 150mm long and 35mm in diameter.

Fourteen pucks are stacked end-to-end in a stainless steel tube. The tubes were positioned vertically to form an outer ring around the Dounreay Fast Reactor.

In December 2012, the first of 90 rail shipments of breeder material was made from Georgemas, a tiny station near Dounreay, to Sellafield in Cumbria.

The journey was understood to have been made under armed escort.

Forty-four tonnes of breeder material in total will be transported by train to Sellafield for reprocessing.

At an estimated cost of £60m, the NDA said it was a cheaper option than trying to deal with it at Dounreay.

Exotics include material containing highly enriched uranium.

Sellafield is expected to receive 40 shipments of exotics over the next six years.

- Published8 October 2014