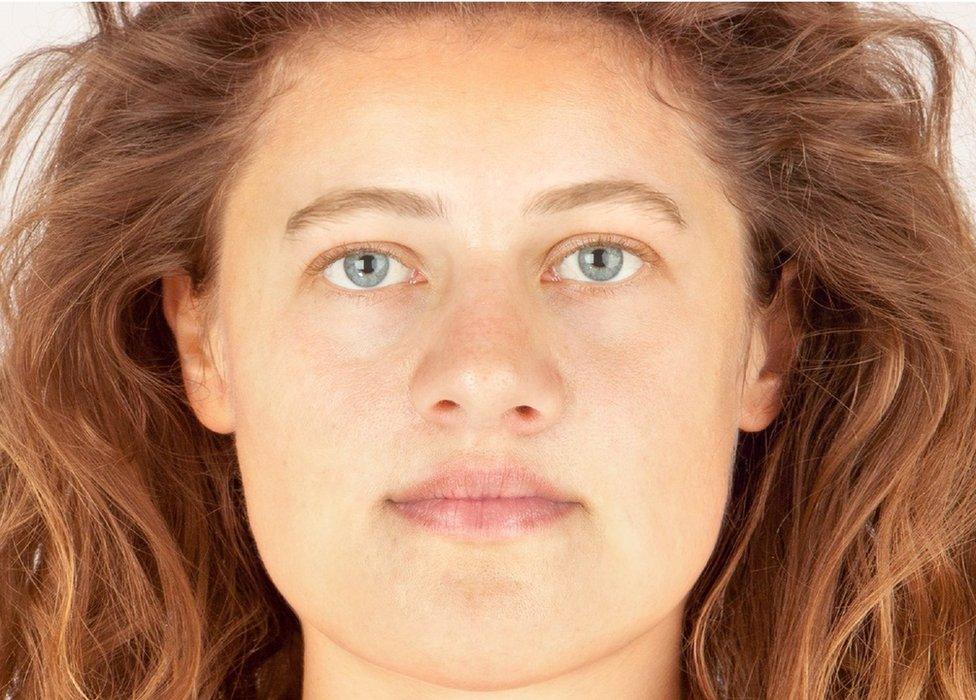

Facial reconstruction made of Bronze Age woman 'Ava'

- Published

Forensic artist Hew Morrison's completed reconstruction which he created using specialist software

A facial reconstruction has been made of a young woman who died more than 3,700 years ago.

The woman's bones, including a skull and teeth, were discovered at Achavanich in Caithness in 1987.

Known as "Ava", an abbreviation of Achavanich, she is the subject of a long-term research project managed by archaeologist Maya Hoole.

Forensic artist Hew Morrison, a graduate of the University of Dundee, created the reconstruction.

Ava's remains, along with other artefacts found with her, are held in the care of Caithness Horizons museum in Thurso.

Unusually, the Bronze Age woman was buried in a pit dug into solid rock and her skull is an abnormal shape which some suggest was the result of deliberate binding.

Ava's skull and other remains were found in 1987

It is believed Ava was part of a much wider European group known as the Beaker people.

Short and round skull shapes were common amongst this group, but Ms Hoole said the Achavanich specimen is exaggerated and of an abnormal, uneven shape.

Mr Morrison, a graduate of Dundee's Forensic Art MSc programme, specialises in creating facial reconstructions.

He used an anthropological formula to calculate the shape of Ava's missing lower jaw, and also the depth of her skin.

Mr Morrison also used a chart of modern average tissue depths for reference.

A specialist examination at the time of the discovery in the 1980s suggested that the skeletal remains were that of a young Caucasian woman aged 18-22.

He said: "The size of the lips can be determined by measuring the enamel of the teeth and the width of the mouth from the position of the teeth."

The shape of the woman's skull has been described as unusual

Mr Morrison created the reconstruction by rebuilding the layers of muscle and tissue over the face.

He drew on a large database of high resolution images of faces to recreate the facial features.

The individual features were then adjusted to fit with the anatomy of the skull based on the underlying facial muscles. The features were then "morphed together", using computer software to create the reconstructed face.

Achavanich in Caithness where the finds were made

Mr Morrison said: "Normally, when working on a live, unidentified person's case not so much detail would be given to skin tone, eye or hair colour and hair style as none of these elements can be determined from the anatomy of the skull.

"So, creating a facial reconstruction based on archaeological remains is somewhat different in that a greater amount of artistic licence can be allowed."

He added: "I have really appreciated the chance to recreate the face of someone from ancient Britain.

"Being able to look at the faces of individuals from the past can give us a great opportunity to identify with our own ancient ancestors."

Ms Hoole said: "When I started this project I had no idea what path it would take, but I have been approached by so many enthusiastic and talented individuals - like Hew - who are making the research a reality.

"I'm very grateful to everyone who has invested in the project and I hope we can continue to reveal more about her life."

- Published12 February 2016