'Incredibly rare' find in Western Isles prehistoric forest

- Published

Prehistoric wood preserved in peat at Lionacleit

Archaeologists have found evidence of early human activity at a submerged prehistoric forest in the Western Isles.

Lionacleit in Benbecula is one of more than 20 recorded sites of ancient woodland that once grew in the islands.

The remains included an early butchery site and stone tools used for preparing food.

Archaeologists have described the discoveries at Lionacleit as "extra special".

They found the remains of the area where animals had been butchered for food during studies of the site last year.

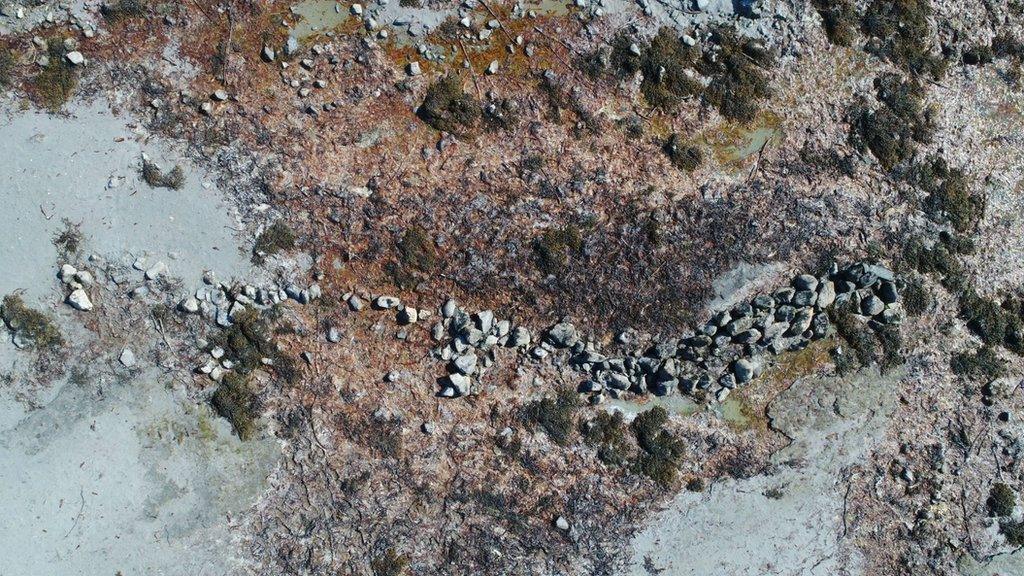

An aerial view of local volunteers mapping and recording the submerged forest

Bone was also found with a piece of quartz from a stone tool and a quern stone, which was used for grinding food.

The Scottish Coastal Archaeology and the Problem of Erosion (Scape) Trust, external, a charity that works out of the University of St Andrews, was alerted to the remains by local resident Ann Corrrance Monk.

Joanna Hambly, a research fellow at Scape, said: "An unexpected discovery during the fieldwork was the realisation that archaeological remains survived in the intertidal zone.

"These include a wall, the possible remains of sub-circular stone structures which could be houses, a quern stone and butchered animal bone associated with struck quartz tools.

"To find the remains of a butchery site is incredibly rare - the survival of a single action in prehistory preserved in intertidal peats."

A quartz flake preserved against the bone it was used to butcher

A prehistoric saddle quern stone found at Lionacleit

Dr Hambly added: "These remains are all much closer to the beach than the forest, and are almost certainly much later in date.

"We don't know how old they are yet, but have submitted samples for radiocarbon dating."

'More or less treeless'

The sub-fossil trees at Lionacleit are the remnants of woodland that was once widespread across the Western Isles. Sub-fossils are matter that has been partially rather than fully fossilised.

Scape said the forest was at its peak about 10,000 to 7,000 years ago and was a rich mix of birch, hazel, willow, aspen, rowan, oak, Scots pine, alder, ash and elm.

From 6,000 to 4,500 years ago the woodland declined, and by about 2,800 to 2,500 years ago the isles "were more or less treeless", said Scape.

Ann Corrrance Monk alerted archaeologists to the find at Lionacleit

The red interior of a prehistoric willow root revealed in a freshly cut sample

Sub-fossilised branch with twigs

Rising sea levels, a wetter and windier climate and human activity were all factors behind the island forest's decline.

"None of these factors is unique to the Western Isles, but the trees growing here were at the limit of their environmental tolerance and so unlike other places, the forest didn't regenerate," said Dr Hambly.

Scape worked with local volunteers and Orkney-based submerged forests expert Dr Scott Timpany, of the University of the Highlands and Islands, on last year's project at Lionacleit.

As well as the archaeological finds, more than 300 trees were mapped, sampled and identified. The majority of the trees were willow, with the occasional birch and Scots pine.

Secondary one and two pupils from Lionacleit School visited the site and helped the project team to visualise the density of the forest by standing on each tree stump to represent the tree that once stood there.

Remains of a wall at Lionacleit

Archaeologists believe the site includes the possible remains of dwellings

The site at Lionacleit, along with others in the Western Isles, is at risk of coastal erosion.

Dr Hambly said: "It would be impractical to preserve the sub-fossil trees or the archaeological remains in situ.

"However, while they are available to us, we can enjoy and learn from them - and this is the approach that Scape takes.

"The submerged woodland and the archaeology at Lionacleit have already given us a great deal of information about the past and we have only just started."

'Dynamic coastline'

She added: "When the radiocarbon dates have been processed, we will write up the story of Lionacleit and review what further research could be done at this fantastic site - or at similar sites.

"This will involve the local community, who will also have a critical role in monitoring the site for inevitable further exposures of archaeological remains along this eroding and dynamic coastline."

School students recreating the forest

Images are copyrighted.