Gaelic language in 'crisis' in island heartlands

- Published

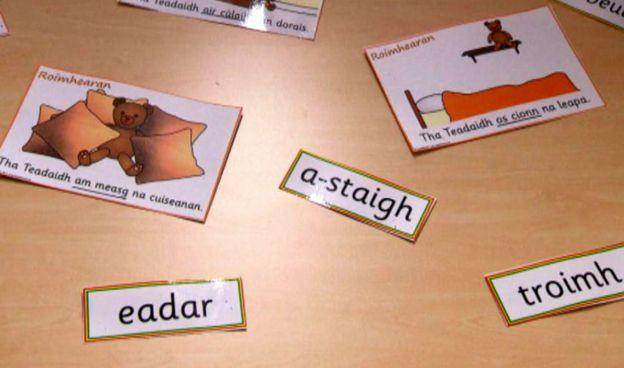

Communities on Tiree were surveyed as part of the research

Gaelic-speaking island communities could vanish within 10 years unless language policies are changed dramatically, according to a new study.

Researchers said daily use of Gaelic was too low in its remaining native island areas to sustain it as a community language in the future.

They have called for a shift away from institutional policies to more community-based efforts.

The study surveyed Gaelic communities in the Western Isles, Skye and Tiree.

The Scottish government said Gaelic was a vital part of Scotland's cultural identity and it was interested in the proposals set out in the new study.

The research - published in a book called The Gaelic Crisis in the Vernacular Community: A comprehensive sociolinguistic survey of Scottish Gaelic - has been described as the most comprehensive social survey conducted on the state of Gaelic communities.

Researchers from the University of the Highlands and Islands (UHI) Language Sciences Institute and Soillse, a multi-institutional research collaboration, carried out the study.

They said the main findings suggested the language was in crisis, and that within remaining vernacular communities of Scotland, the social use and transmission of Gaelic was "at the point of collapse".

But the research also suggested there had been some success with national policy on Gaelic, such as increasing the number of pupils in Gaelic medium education.

'Language loss'

Prof Conchúr Ó Giollagáin, of UHI, said there were "immense challenges" involved in reversing the ongoing decline in the use of Gaelic in its island heartlands.

"Our statistical evidence indicates that the Gaelic vernacular community is comprised of around 11,000 people, of which a majority are in the 50 years and over age category," he said.

"The decline of the Gaelic community, as especially shown in the marginal practice of Gaelic in families and among teenagers, indicates that without a community-wide revival of Gaelic, the trend towards the loss of vernacular Gaelic will continue."

Researchers said there had been some success such as in numbers of children in Gaelic medium education

He added: "We found a mismatch between current Gaelic policies and the level of crisis among the speaker group which must be addressed to face the urgency of the language loss in the islands.

"The primary focus of Gaelic policy should now be on relevant initiatives to avert the loss of vernacular Gaelic."

'Constantly under review'

Iain Caimbeul, a research fellow at UHI's Language Sciences Institute, said: "We hope this research will be valuable to those interested in seeking to shift public policy assumptions from a sole dependence on the school system for creating the next generation of fluent Gaelic speakers.

"It is vital that we change the basis for allocating resources to protect against further decline."

The Scottish government said it supported efforts to improve the use of Gaelic.

A spokeswoman said: "We are interested in the proposals in the book and look forward to discussing the value of current initiatives and the new structures suggested to strengthen Gaelic in the islands.

"Although the Gaelic language is in a fragile condition there are a range of policies and interventions in place to promote the learning, speaking and use of Gaelic in the islands and these are constantly kept under review."