The snowstorms that buried homes and sheep

- Published

The authorities and military responded to severe weather in 1955 with Operation Snowdrop

With the UK in the grip of a prolonged spell of snow and ice, residents of the north Highlands have been recalling severe snowstorms that hit the area almost 70 years ago.

During the severe winter weather of January 1955, 18-year-old John MacRae found himself walking miles in snow drifts in a race against the time to tell his army barracks where he was.

The young National Service recruit had been on leave from Fort George in Inverness and needed to report to his home village police station that he would be late back because of the atrocious conditions.

He got off the train in Wick, about 20 miles north of his home in Dunbeath, but all the roads were blocked by snow. There was no way through.

"If I didn't report to my local police station I would be absent without leave - something that was a serious offence at the time," says John.

"I didn't want to be absent without leave. I wanted to serve out my two years National Service, and see the world."

John MacRae walked 14 miles across snow drifts to report he would be late back to barracks

John, who was soon to embark for Egypt, convinced a council roads crew to give him a lift from Wick in a snowplough, a mighty machine dubbed Big Mac. He was told he could he ride as a passenger, but only at his own risk.

About six miles into the journey home, the driver found he could go no further because of the depth of the frozen snow drifts.

John decided he would walk the rest of the 14 miles home.

"If I'd had a walking pole I could have reached up and touched the telegraph wires above me," John, who is now 86, told the BBC. "The snow was that deep.

"Looking around the only other sign of life were helicopters."

John was witnessing Operation Snowdrop, an effort involving the military and local authorities to bring help to snowbound crofts, farms and rural communities in Caithness and Sutherland.

The storm in January lasted for most of the month, with blizzards and high winds. It was quickly followed by an intense days-long storm in February when winds gusted to 70mph and snow piled up in drifts 10ft (3m) to 13ft (4m) deep.

Helicopters were the only way to reach the vulnerable because roads were blocked.

An aerial view of a snowbound farm with a letter "H" created in the snow as a plea for assistance

Those in need of help marked out large letters in the snow - "F" for food, "C" for cattle fodder or "D" for doctor. Guidance on the messages was issued via BBC radio news.

People who did not hear the broadcast cobbled together their own appeals for help including writing "SOS" or creating a large letter "H".

HMS Glory, an aircraft carrier that had seen action in World War Two and the Korean War, was sent to Loch Eriboll on the north west Highland coast to assist with the relief effort.

Royal Navy helicopter crews flew sorties from the ship to deliver supplies.

Working with the Scottish SPCA, the air crews also rescued sheep exhausted from trying to find food in fields covered in thick snow. The animals were bundled into helicopters five at a time and flown to the shelter of nearby crofts or farms.

RAF air stations at Kinloss and Lossiemouth also provided assistance. Neptune anti-submarine aircraft were flown low over the countryside so bales of hay could be dropped near livestock.

'Big misunderstanding'

John MacRae's embarkation leave had been eventual from the start, days before his chilly 14-mile trek home to Dunbeath.

He had decided to spend his time off visiting a friend in Edinburgh for a couple of days.

John asked his girlfriend at the time if she would join him on the trip, and they left Wick as snow fell.

"We got about three miles out from Wick station," he says. "The snow was really coming down now and the train got stuck in a drift."

A local railway worker offered the train's six passengers the safety of his home for the night.

"There was nowhere for us to sleep and we just sat around, but at least there was a peat fire to keep us warm," says John.

"The railway worker had a young family and they couldn't offer us any food, which was understandable, because they needed what they had to keep themselves going through the bad weather."

The following day, a train was sent up from Inverness with hot food for the Wick train's staff and passengers.

The Inverness train also got into difficulty in the snow and John, due to his sensible decision to wear warm clothes and stout footwear, was selected to walk down the tracks to collect the food.

Eventually, he and the other passengers were able to resume their journey south.

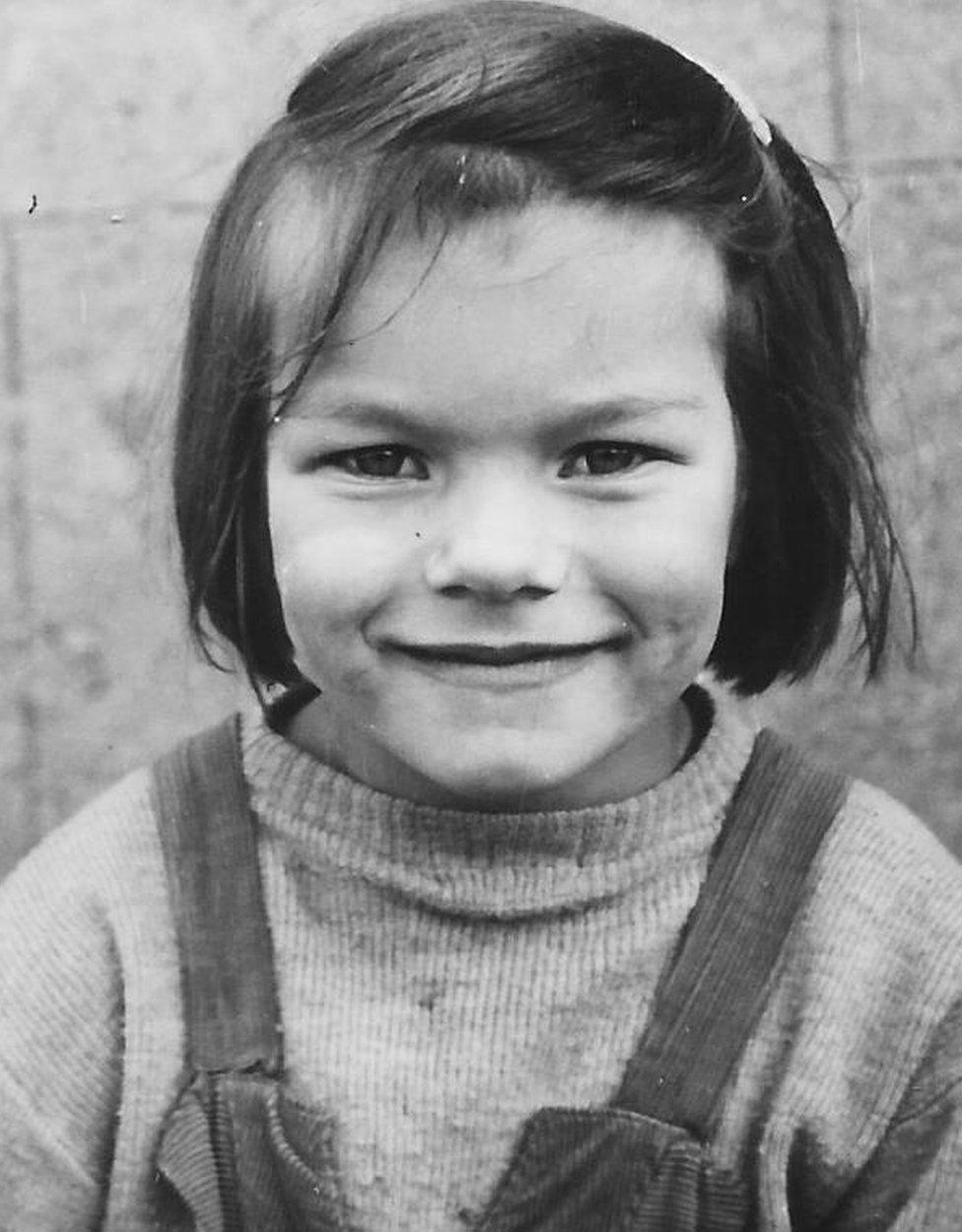

Helen Gibson was eight when the storms came in 1955

Stopping in Inverness, John and his girlfriend stepped off the train to be met by journalists and photographers - all eager to get a story about the snowbound-train's newly-weds.

"There had been a big misunderstanding," John says.

"Because the girl I was seeing worked in the registry office in Wick, and we had been seen leaving her work together, someone had put two and two together and got five.

"Whoever it was thought we'd got married and then got stuck on the train in the snow. They had phoned the papers with what they thought was a good story.

"I'm not sure the press were very happy when we told them it wasn't true."

Following his trip to Edinburgh, John travelled back to Wick by train and then tried to get back down the road to his home in Dunbeath.

After Big Mac the snowplough foundered in the snow drifts, John set out on foot at about 13:00.

"The snow was frozen hard, so it wasn't too difficult to walk on. The worst it got was sinking down to my ankles," he says.

Last onion

John arrived, hungry, at his parents home at about 19:30.

He says: "My mum made me a meal because my dad was a gamekeeper, so there was usually venison in the house. Mum fried some up with the last onion she had.

"I can still remember the taste of that meal."

John reported himself at his local police station and avoided falling foul of military rules.

He, along with a fellow National serviceman who was returning late from leave, eventually made it to Fort George - and a subsequent posting to Egypt.

But any hopes John had of being congratulated on his efforts in the snow quickly melted away when a regimental sergeant major spotted the pair on the parade ground and gave them a roasting for not being back on time.

February's storm left a lasting impact on Helen Gibson, who was eight at the time and living on her parents Gordon and Mary Gibson's small holding at Skaill, near Forss.

She recalls trudging off reluctantly one morning in her welly boots in the snow on her mile-and-a-half walk to school, before her dad caught up with her in his van and told her the school had been closed.

"As the day went on I remember snowflakes started falling like large feathers," says Helen.

Helen's home near Forss, which was partly buried under snow in February 1955

The following morning, Helen's dad called the family to come to the door of their single-storey property.

Helen, who is now 76 and lives on the Isle of Man, remembers it being very dark inside the house and behind the door her father revealed a wall of snow.

"The snow had been blown right over the top of the house," she says.

"There must have been 10ft to 12ft of snow and my father had to dig a tunnel out and then cut steps into a snow drift up to a field where our sheep were.

"Sheep aren't stupid, and they had sought shelter by a wall. They were covered in snow but there was a space created between them and the wall which allowed them to breath.

"For a child, it was a magical time. School was off and we played in the snow, building igloos and at night we read books or listened to the radio. It felt it was like that for weeks."

But as the days wore on the fun faded a little.

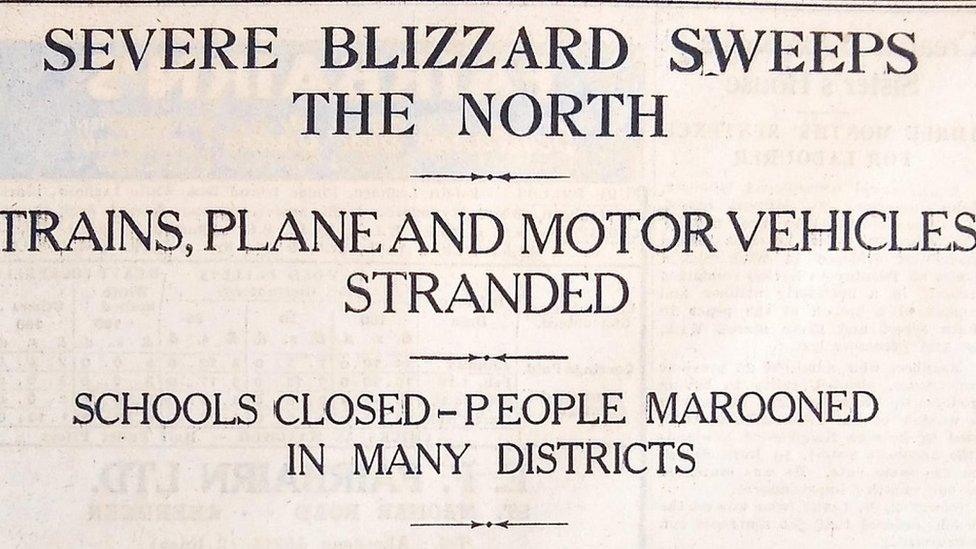

A headline in the John O'Groats Journal from the time of January's storm

The pipes were frozen and the family melted snow for water. The electricity was also off, though they were able to get by with candles and were warmed by their Rayburn cooker.

While there was enough food for their animals, supplies were running low for the family.

A slab of salted, dried cod that had been hanging in the scullery was taken down and soaked in melted snow in the kitchen sink. It was then soaked in hot water and boiled.

"On my travels I have eaten salted fish in Norway, but this was nothing like that," she says.

"It tasted like salted cardboard - grainy and dry."

With supplies dwindling, Helen's dad made himself a pair of snowshoes and headed off to the main road to Thurso to restock.

"My mum must have been so worried," says Helen. "He was not back until the following day and there was no way of knowing if he was safe while he was away."

And then one day the adventure was over, says Helen. Tractors fitted with snow ploughs were able to reopen the roads, and school was back on.

She says: "We were used to winters with snow drifts 6ft deep. But that winter was exceptional."

The Nucleus archives and Highlife Highland have more information on Operation Snowdrop in an exhibition that is available to view online, external.