World War One 'still affects Shetland to this day'

- Published

Janet Hardy, who lost three sons in the conflict, unveiling the War Memorial in Lerwick in 1924

In comparative terms, Shetland had one of the highest losses of life in World War One. The conflict had a huge impact on the population that made up the towns and villages of the islands, which can at times seem apart from the rest of the UK.

According to the 1911 census, Shetland had a total population of 27,911. Of this population, more than 600 servicemen died in the war.

But according to local historian and history teacher Jon Sandison "the total of the war memorial and the Roll of Honour is closer to 700".

This loss of life, in proportion, is considered one of the largest for any area of the UK.

John Taylor, a former serviceman living in Shetland, said: "Throughout the country, 1 in 45 people were lost, but in Shetland it was about 1 in 38. Percentage-wise, the loss here was greater than the rest of the UK."

'Decimated by war'

Bobby Hunter, Lord Lieutenant of Shetland, said: "It still leaves an effect. Folk still talk about folk who were lost in the First World War.

"I had my own grandfather and grand-uncle, two brothers, who were lost. It still affects folk to this day."

The War Memorial in Lerwick was unveiled in January 1924 by Janet Hardy.

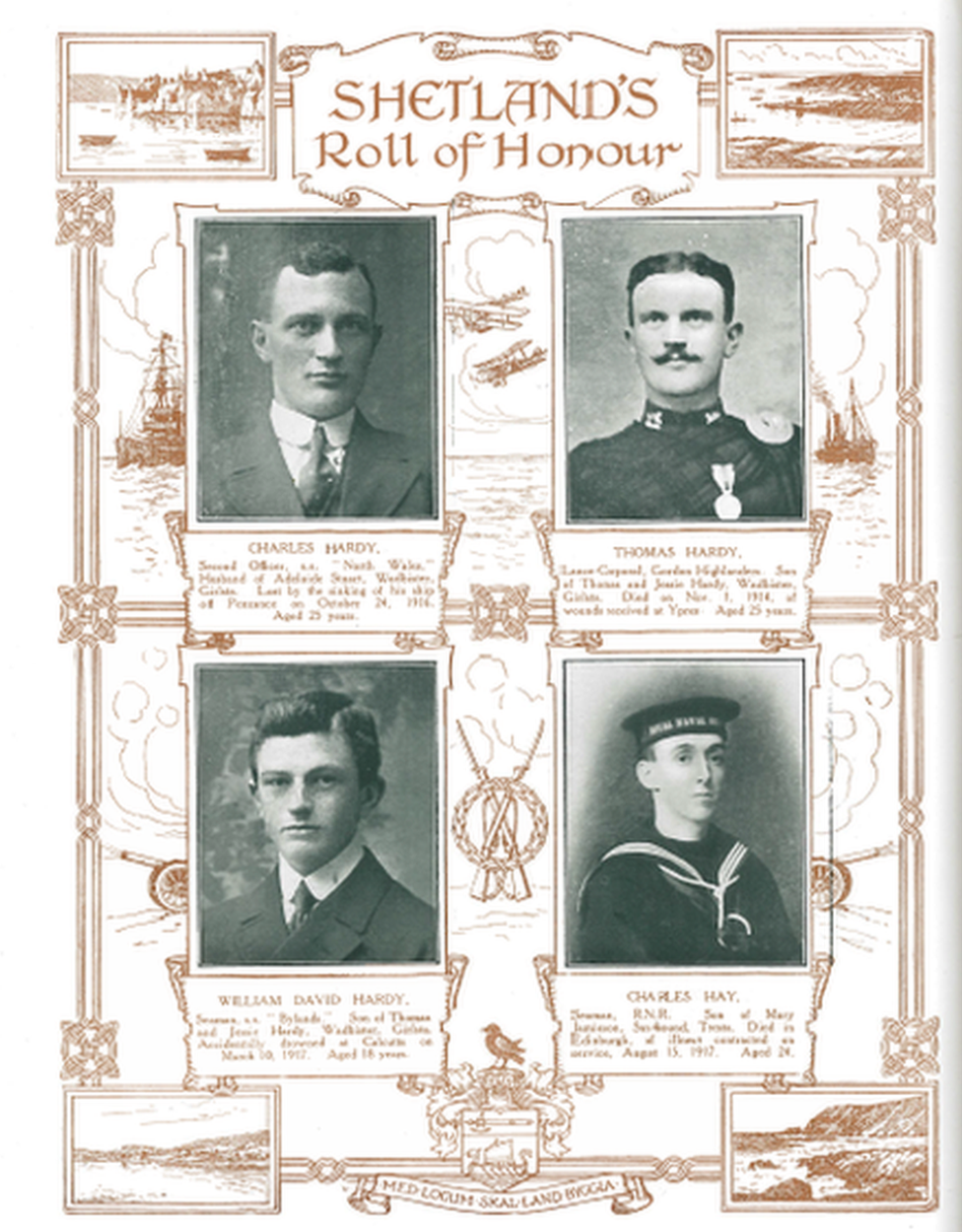

The Hardy brothers (top row and bottom left) who all died in the war

Her family experienced the pain that war inflicts perhaps more keenly than any other family in Shetland. Three of her sons, Thomas, Charles, and William, went to war. None returned.

Thomas died when the ship he was serving on in Penzance sank in 1916. Charles died in November 1914 from wounds sustained in Ypres. William died in Calcutta in 1917 from drowning. As Mr Taylor said: "A lot of families were decimated by the war."

There were, however, positive stories; stories of brothers surviving the war gave people hope.

The Cluness family ended up sending five sons to the war. Remarkably, all five came back.

What did Shetland contribute?

Despite its distance from mainland UK, Shetland was active in sustaining and supporting the war effort, in inventive and innovative ways.

Knitting in the Shetland Islands has for centuries been a practical pursuit. Due to the often harsh weather, making use of wool has been necessary for survival.

Those knitting skills were underlined and put to the test in World War One.

Thousands of women from across the Shetland Islands produced various types of knitted goods for troops.

They were part of the Queen Mary's Needlework Guild. Its aim was to provide clothes and knitted goods to servicemen. And Shetland women did just that, producing more than 15,000 knitted items.

Their efforts did not go unnoticed. After the war, thousands of soldiers sent letters of thanks to those women who had provided them with clothes to help them see out cold winters.

This was just one way Shetlanders used wildlife and nature to pitch in with the war effort.

The 'Egg Collection for the Wounded' campaign aimed to distribute eggs from towns and parishes across the UK to the war wounded, often in hospitals.

About 32 million eggs were sent to feed wounded soldiers in areas of France and Belgium. Shetland contributed a total of 300,000 eggs for the effort.

Children collecting eggs for 'Egg Collection for the Wounded'

One more contribution from the Shetland Islands is perhaps more surprising - moss.

The contribution of sphagnum moss was classed as "significant", with the plant material being used for "surgical dressings" due to its antiseptic qualities, making it a first aid essential.

Days were especially organised so that locals could go out to gather moss.

Mr Sandison said: "There was a moss day in August 1917. People went to the hillsides and collected 2,500 bags of moss. The following year they sent 3,000 bags."

Those 5,500 bags of moss were sent to help wounded soldiers.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

What happened then?

The 1911 census also revealed that Shetland had a majority female population - a majority of about 2,500.

Mr Hunter explained: "The women were left at home with the families. They had to work on the crofts so they were left with the heavy end of the stick when the men were away."

They were affected by men being away and from the toll of those who did not return - and the whole of Shetland was impacted through that generation and beyond.

Mr Sandison added: "Overall, most men did come home. But, when they did come home, they had to fit back into society.

"A lot were affected for the rest of their lives and their family had to deal with that

"The loss was very large for women. We often speak about the 'Lost Generation'.

"Perhaps there was another lost generation; the families who went through that and those who were left at home."

- Published9 November 2018

- Published5 November 2018

- Published17 July 2024

- Published5 August 2014