The story of weather watching in Shetland

- Published

The Observatory in the 1920s

The brainchild of a polar explorer, Shetland's weather station helped measure the ozone layer and played a role in the aftermath of the Chernobyl disaster. As the observatory approaches its centenary next year, former employees have been looking back at its history.

In December 1911, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen was the first to lead a group to the South Pole as part of his efforts to find out more about the most northerly parts of the globe.

After a Polar Sea expedition in 1920, Amundsen wanted to compare notes on the Aurora Borealis he observed.

Amundsen became the first person to reach the South Pole

The Norwegian government then lobbied for the UK to establish a meteorological observatory in the Shetland Islands.

In its operational life, the observatory has measured the Aurora Borealis - known as "the mirrie dancers" in Shetland - and studied geomagnetism and daily weather patterns, as well as feeding into the daily shipping forecasts.

Amundsen wasn't the only Polar connection. In the 1950s, Shetland became a training site for the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

It was "like a sergeant's mess" according to former scientific assistant, Allen Fraser.

"Shetland gave these young lads a taste of what being away from home was like in an isolated spot," said Allen.

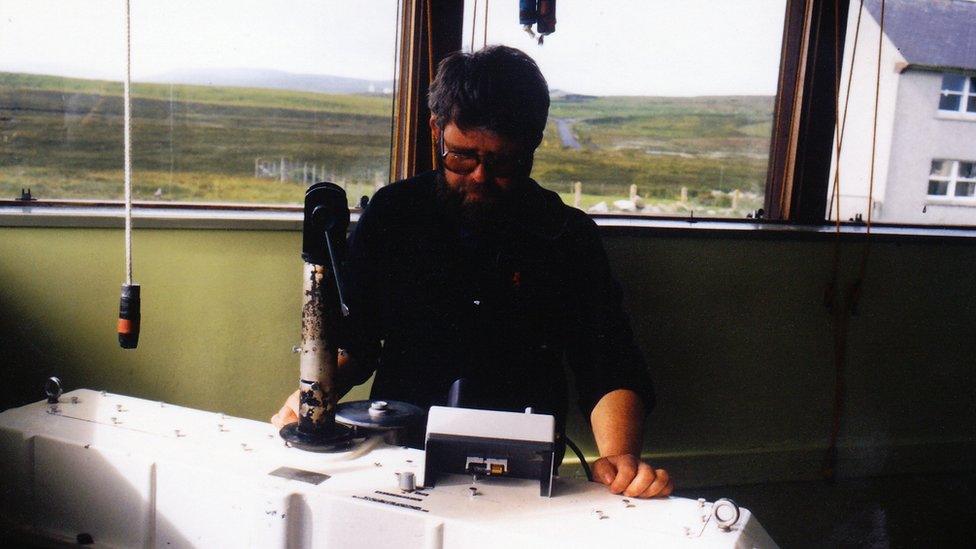

The machines used in the Lerwick Met Office

The research carried out by the BAS is now used by climate scientists documenting changes in the earth's weather history.

"We documented everything manually and radioed it to the Falkland Islands, where it was sent on and processed in Argentina," recalled scientific assistant Kenneth Hughson.

Forming relationships and teamwork was an important part of the time scientists spent in Shetland and it prepared them for heading to the Antarctic.

"They got an idea of how it was living together, dining together, socialising together," Allen said.

Measuring the ozone layer

Training given in Shetland also played a part in later work to identify a major climate concern.

A Dobson Spectrometer, known as a Dobson, was one of the tools used in Lerwick. It measures the thickness of the ozone layer.

"It's still there and used today. There are only two in the northern hemisphere and two in Antarctica," said Allen.

The graduates who were trained on the Dobson in the 1950s included Joe Farman, a physicist who was later credited with helping identify the hole in the ozone layer.

In 1985, he published the findings of a study looking at the concentration of the ozone layer over Antarctica in the journal Nature.

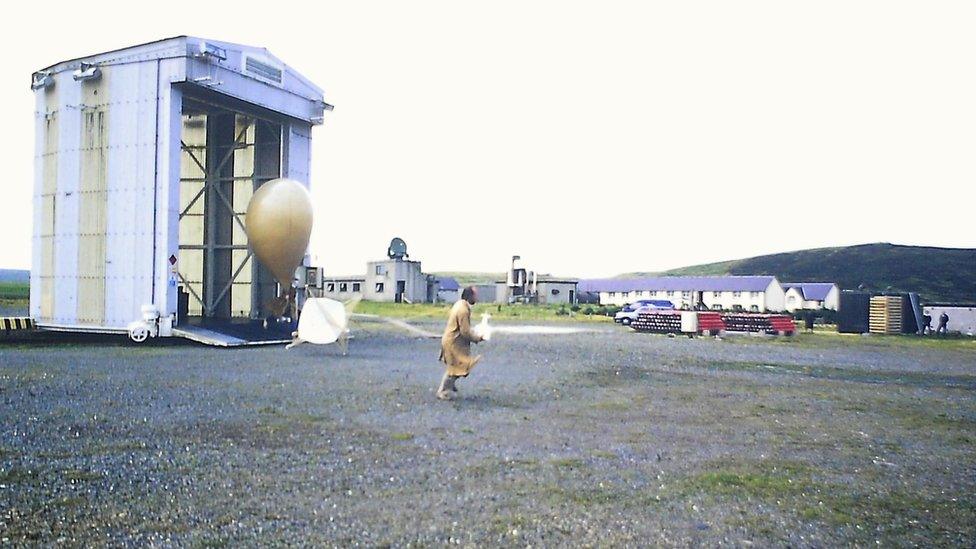

Balloon tests take place regularly for atmospheric readings

The scientist recalled his time spent in Shetland in an interview with the Financial Times in 2010.

He spent six months training there in 1956, learning about instruments like the Dobson, before going to work in Antarctica.

The Dobson was important for training and getting Antarctic recruits ready for their work. But its ongoing monitoring was equally vital.

"It wasn't just for training," said Allen. "It measured the ozone over Shetland and helped build a (long-term) picture."

The Chernobyl disaster

The Shetland weather station's involvement in world-changing events continued when in April 1986, staff there were among the first to learn of the Chernobyl disaster.

The day after the explosion at the power station, staff at the Lerwick Met Office were asked to test rainwater to determine levels of radioactive material.

Allen at work in the observatory

"It was a Sunday, I was on duty, and we got a call from Dounreay Nuclear Power Station," recalled Allen.

Getting such a call was unusual, but their questions were even more so.

"They were worried - their workers coming on duty were triggering radioactivity alarms," he said.

It had been raining at Dounreay and staff had been stepping in puddles that contained radioactive water, which was setting off the alarms.

The Shetland observatory's superintendent, Alan Gair, was asked to take measurements.

'Mildly radioactive'

He said they had regularly collected rainwater and sent it for processing to document atmospheric readings.

"They desperately wanted us to send off a rain bottle," Alan recalled.

"It was raining - I went out into it not thinking it might be mildly radioactive.

"I remember being nervous, not knowing what I was going out into."

Rainwater samples were collected and sent to be analysed.

News of what happened at Chernobyl was initially suppressed by the Soviet Union, meaning the Shetland observatory staff were among the few to learn about the disaster before it became public knowledge.

Allen launching a weather balloon at a staff reunion

For those who worked at the Shetland weather station it was more than just a job. They became part of a community, with their families also spending lots of time together.

"I have very happy memories of the place. It was my home," says Denise Nicolson, whose father Harry Tait is a former site superintendent.

In recent years, she has been collecting memories from former workers at the site.

"It's been a great way to reconnect with folk from my childhood, and it's been an important link to my dad," she said.