The world's earliest 'babies' were fish from Orkney

- Published

The primitive fish had a heavily-armoured head and could grow up to a meter long

The earliest "babies" known to science have been uncovered in the remains of a primitive fish found in Orkney.

Researchers say the unborn embryos discovered in a fossil from the island of South Ronaldsay date from 385 million years ago.

The Watsonosteus fletti, now part of the National Museums of Scotland collection, gave birth to live young.

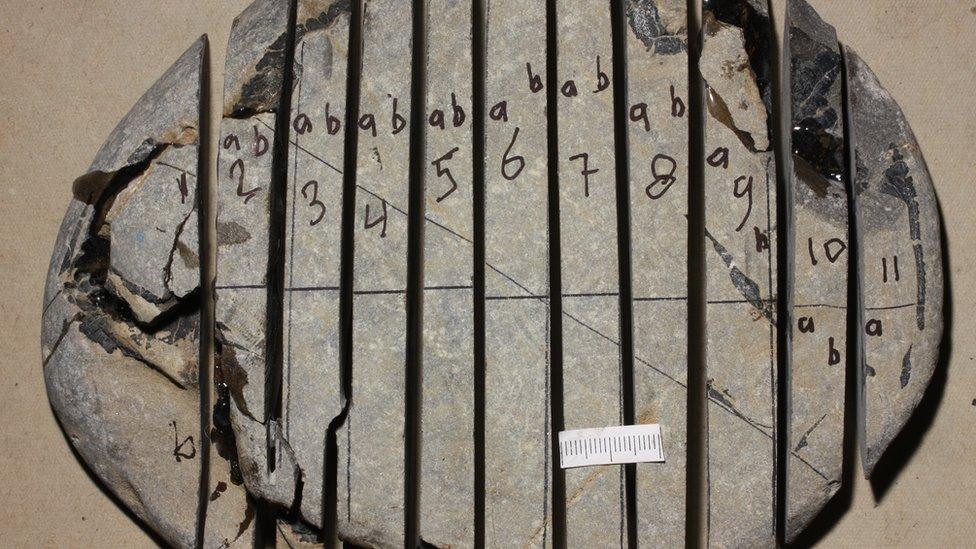

The tiny remains were discovered when scientists looked at slices cut through rock formed in the Mid-Devonian epoch.

They are at least three million years older than the previous record holders - fossilised embryos from Australia.

The fish - Watsonosteus fletti - lived in a huge lake in South Ronaldsay

The fossilised embryos were recognised when slices from a nodule of rock were examined under a powerful microscope

Details of the discovery have been published in the journal, Palaeontology.

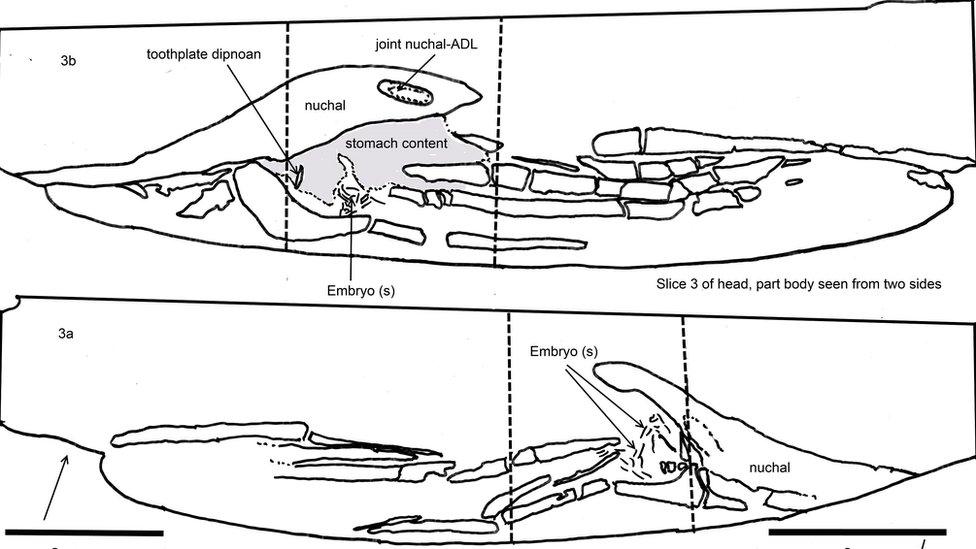

Lead author of the paper, Mike Newman, told BBC Radio Orkney: "We were sectioning just randomly really, and we saw what makes up the bones, even though it is fossilised. And then we went through the body cavity.

"Inside we found the gut contents. But then there were these strange, very thin, little bones. And it became apparent, by looking at the detail of these bones, that they were actually the young of the adult.

It seems the fish would have given birth to live young, rather than laying eggs.

But she died, and sank to the bottom of the lake, while she was still pregnant.

Looking at the prepared slices of rock under a powerful microscope revealed how the fish's bones were formed, the contents of her guts, and the unborn babies in her womb

At first researchers thought the bones could have been small fish that she had eaten. But they seem to be still in development, and therefore wouldn't have been capable of independent life.

And, they say, they can be confident of the dating because of a clear pattern of layered rock laid down in the bottom of the ancient lake, and because the whole ecosystem is distinctly different - and much earlier - than the Australian examples.

They accept that now they know what they're looking for, it may be possible to find even earlier embryos in the fossil record. But, at least for now, these are the earliest babies yet recognised.

"There will be more discoveries which will probably push it back a little bit more", Mike Newman says. "We may even get back another 10 million years, when we look in other localities which have older, similar, fossils."

Details of the discovery are published in the journal Palaeontology

The embryos join a long list of Scottish fossil firsts, according to Dr Stig Walsh from the National Museums Scotland.

He said: "Scotland and the isles have a fantastic fossil record. Orkney, in particular, is really important. That Orcadian lake was host to a huge number of life forms.

"We seem to have the firsts of everything. We have the first land animal. The first backboned animal that came onto land. We have the earliest terrestrial ecosystem. And when I heard what they'd discovered I thought, 'Yes! We've got another one.'

"It means basically that the first babies were Orcadians."

- Published26 August 2020

- Published18 February 2016

- Published5 August 2014