I work at one of the world's most remote museums

- Published

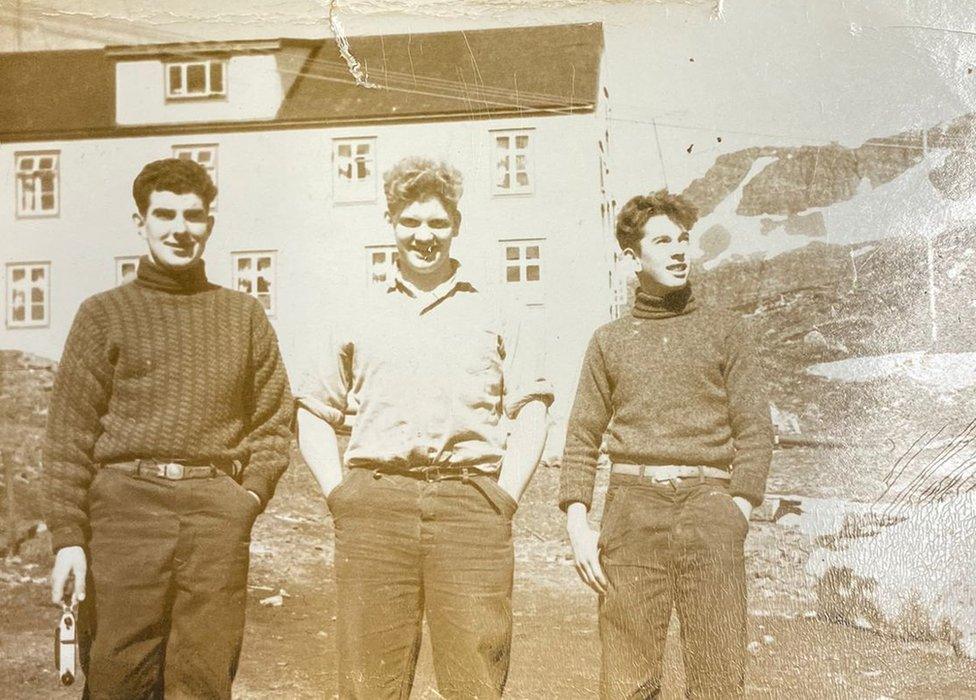

Helen Balfour (centre) is pictured with fellow museum workers Lauren Elliott, left, and Aoife McKenna

A Shetland woman has travelled thousands of miles to work in one of the world's most remote museums.

South Georgia island is in the South Atlantic, and its museum attracted visitors from around the globe.

However, staff were asked to leave in March 2020 as Covid-19 spread across the world. It has now reopened.

Helen Balfour read about the museum in a BBC article, and successfully applied to be an assistant on the island 8,000 miles (12,875km) away from her home.

The 23-year-old was attracted by her love of museums and heritage and her family ties to the island, as her grandfathers were whalers in the area.

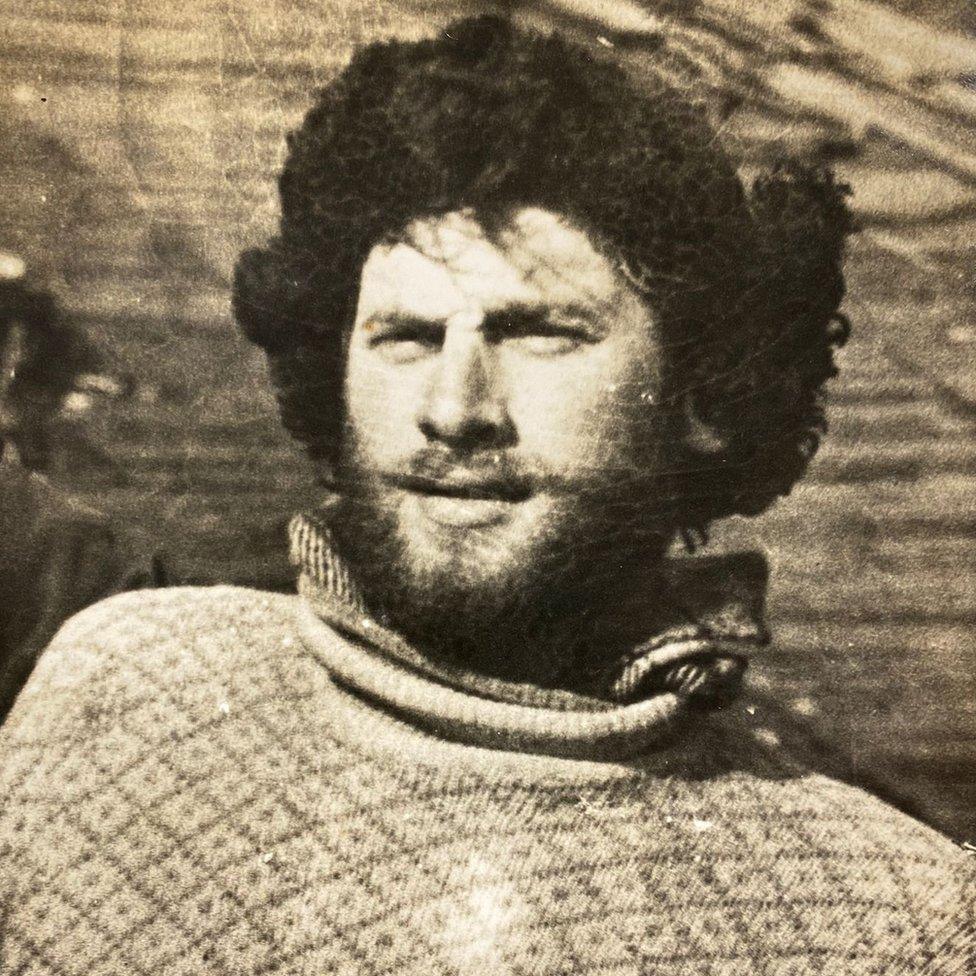

Helen's maternal grandfather Alan Leask, right, was a whaler in the area

The long land, sea and air journey to South Georgia took her three weeks.

"I heard about the South Georgia museum first from an article that was written for the BBC and my dad saw it online and he sent it to me," she told BBC Radio Shetland.

"And because of family connections to South Georgia I just found it very interesting.

"My great-grandfather was here in the early 30s, and his sons - including my grandad - worked here. My other grandad was also here."

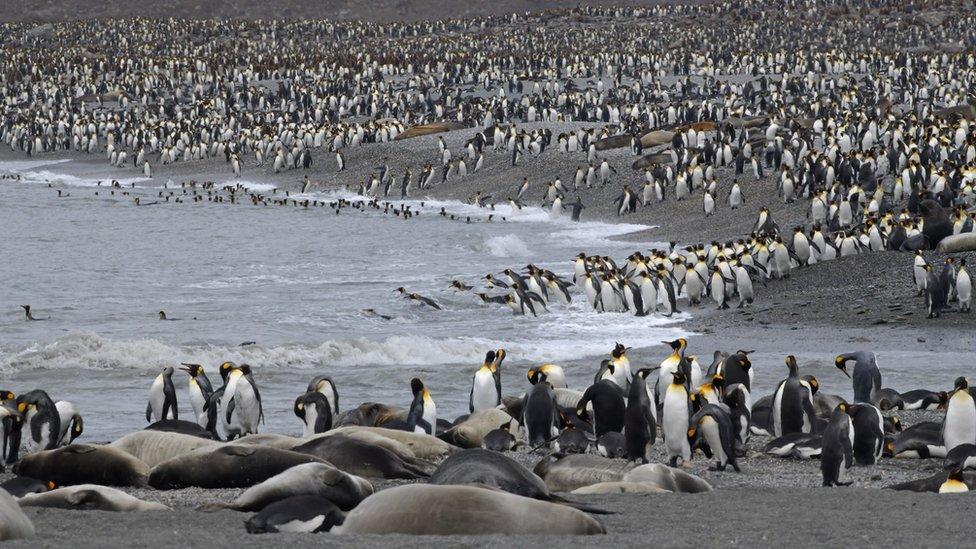

An elephant seal pup near South Georgia's museum

Helen got in touch with the team and asked if she could apply for a job, and successfully passed the interview.

Getting there involved taking the ferry from Shetland to Aberdeen, then the train to Oxford, a flight from Brize Norton to the Falklands, then another boat to South Georgia.

"I left home on 2 October and we got here about the 22nd, it took me a while to get here," she said.

"We were in the Falkland Islands for five days and then the boat journey was another five days.

"It's really special to be able to come here."

The island itself is a tough place to work.

Although it is closer to South America - and the South Pole - than to London, South Georgia has been a British island since the 18th Century, having been claimed by Captain James Cook.

The King is head of state, and the flag features the union jack.

However, the name of the ghost town where the museum sits, Grytviken (pronounced Grit-vicken), gives a clue to the island's history.

The settlement was named by Swedish explorers in the early 20th Century (the name means Pot Cove). In 1904, Norwegians opened a whaling station there to process the whales' meat, blubber, and bones.

In the next 60 years, more than 175,000 whales were killed in the waters of South Georgia alone - processed at Grytviken and other stations along the shore.

But, by the 1960s, the industry had burned itself out - there were no longer enough whales to catch.

Grytviken was abandoned, but a relatively grand villa - built in 1914 - remained usable.

Helen's father's dad Jimmy Balfour also worked in the seas of the South Atlantic

In 1989, David Wynn-Williams, a British Antarctic scientist, suggested turning the villa into a museum, external. The project was taken on by Nigel Bonner and it opened in 1992, originally focused on whaling, but now with a broader approach.

The South Georgia Heritage Trust (SGHT), which runs the museum, is based in Dundee.

Fresh food in South Georgia is rare, the internet connection is poor, and, at times, the wind is strong enough to tip over helicopters.

Helen's grandfather Jimmy Balfour first visited South Georgia in the 1950s.

After a decade of whaling, he worked on one of the final whale catcher vessels which worked out of Grytviken.

Penguins are also a major South Georgia attraction

Her other grandfather, Alan Leask, started whaling aged 16. Her great-grandfather, Thomas Balfour, was also a whaler 20 years before.

Helen is already loving the adventure - and the wildlife, which includes penguins and elephant seals.

"It's quite amusing. There's been a lot of nights where we've all just been standing looking out the window looking at all the drama that goes on when the mums leave their pups behind," she explained.

"We all carry broom handles just in case one of them gets a bit too close, they can be quite territorial.

"They're a bit different from the seals that you would see in Shetland."

The new museum assistant is helping in the shop and with tours, and is looking forward to getting to know cruise ship passengers.

"We're expecting thousands of visitors," she said. "I think it's going to be lovely."

- Published20 January 2022

- Published9 May 2018