Beware of geeks bearing gifs

- Published

Thousands of Britons fall victim to hackers each year

So, you've had your debit card "skimmed". Someone has copied the numbers, and has sold it into a vast industry in cybercrime.

What happens? Your bank calls you, and the chances are, you're reassured that the Rolex watch you appear to have bought in Sofia won't be charged to your account.

You relax and promise to guard your password and pin numbers more closely. It looks like a victimless crime. And that's often how the geeks behind cyber-crime justify what they've done.

This I know from the Edinburgh International Book Festival, where, on Sunday, I took part in a fascinating session on 'DarkMarket', the book on the subject by Misha Glenny, one time Balkan war correspondent for the BBC.

His book is named after one of the notorious criminal websites selling hardware, software and a lot of numbers. It delves into an uber-murky world where everyone's hidden behind code names, their whereabouts often hidden by the ability to pretend to be at a computer anywhere in the world - the more lawless, the better.

No-one is what they seem, everyone's a criminal and you're in the company of intrinsically untrustworthy people, except for those from law enforcement who are tripping over each other to infiltrate the cyber-crime fraternity [yes, it's 95% male].

In a moment of pure comedy from a book that veers between entertainment about the geekiness of it all and the scary extent of unchecked lawlessness on the web, Glenny relates how the US Secret Service was unwittingly investigating a secret agent from the FBI. And vice-versa.

Notorious for Washington in-fighting, the two organisations only found out when investigators from the UK informed them they were onto each other's men.

Moral compass

Less comic is the role Glenny spells out of Ukrainian and Russian secret service, who have turned a blind eye in Odessa, the city notorious for its organised crime, so long as the geeks don't soil their own Ukrainian or Russian nests.

Likewise, the hackers and carders tend to avoid scams involving '.com' websites or US dollars, as those risk them coming within the interests and reach of the US authorities. That, alarmingly, makes European cash all the more attractive.

The profile of the hackers is young, brilliant, motivated to impress their peer group and socially isolated. They learn their skills in bedrooms from Germany to Nigeria to Sri Lanka to Istanbul in their early teens, when they've yet to to get hold of a moral compass.

That's why Misha Glenny criticises the simple response that hackers get jailed, particularly if they find themselves incarcerated in a penitentiary for white collar crime, where they can build up formidable networks for subsequent exploits.

That lack of moral compass is where the notion of a "victimless crime" comes in. Because of course, it's anything but.

Your bank may write off the Bulgarian Rolex, but it's spreading the cost of these losses across all its customers and through the insurance industry.

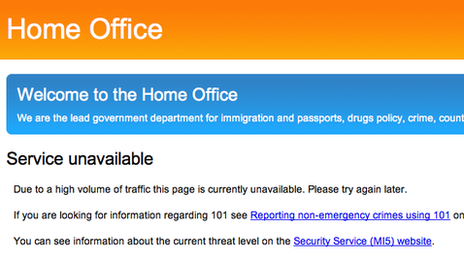

And while Misha Glenny cracked open the hackers' fraternities and got the inside scoop from some of the best of law enforcers, what he couldn't find out is how much banks are losing from cyber-crime.

After all, they've got reputations to protect, haven't they?

- Published8 April 2012

- Published4 May 2012