Banking on more competition

- Published

Things have not worked out quite as expected for the Clydesdale

Four years ago, Edinburgh looked doomed. Its two giant banks had required enormous rescue packages.

I was fielding questions - mainly from London - about how the Scottish capital would handle the disaster for jobs, supplier companies and the self-confidence of the Scottish financial sector.

It's been an often painful process for everyone. Today, we're hearing of hundreds more jobs to go at Lloyds Banking Group. But the loss of financial jobs has been much harsher in London. And neither Edinburgh nor London nor New York nor Zurich have taken as big a reputational hit to their financials sectors as had been expected.

Although decision-making power at RBS, and even moreso at Lloyds/Bank of Scotland, has largely moved south, others have moved in and grown.

As a testament to Scottish financial sector skills, Edinburgh is now the headquarters to three new, standalone banks: Tesco, Virgin Money and, now, Sainsbury's.

Sainsbury's is taking a similar route to its supermarket rival. Tesco had a joint venture with RBS, which it bought out.

Sainsbury's this week announced it's spending £248m buying out the 50% share in Sainsbury's Bank held by Lloyds Banking Group (via Bank of Scotland) since it started 16 years ago. It's probably a good time to pick up low value bank assets, if you have the appetite for them.

Tesco Bank has found it a tough task to move beyond simple savings products to get into mortgages and on into current accounts.

That is going to become even more complex from September, when current account providers will have to provide an easy electronic switching service to customers, as one of the methods being required by government and regulators to encourage more competition.

Sainsbury's Bank has been less ambitious than Tesco, so far, but standalone status, wholly owned by the supermarket chain, may give it bigger targets.

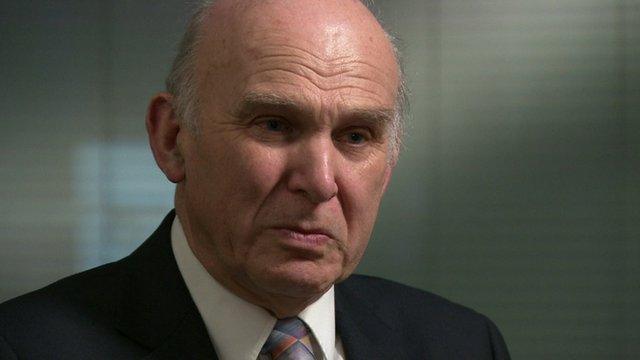

That would certainly be welcomed by government. The Business Secretary, Vince Cable, was in Edinburgh last Thursday, at the grand headquarters of Royal Bank of Scotland.

Green street lights

This was to talk at a conference about another bank that's chosen Edinburgh for its financial sector skills; the Green Investment Bank.

It's a rather different beast, using £3bn of government funding to seek out low carbon investment opportunities where the market is reluctant to commit to risks. There was pressure for it to have the opportunity also to borrow on the capital markets, but the Treasury isn't allowing that until UK debt begins to come down. It had hoped that would be in 2015, but that schedule looks very unlikely now, so the Green Investment Bank may have to stay constrained for a few years longer.

For now, however, with its first five months showing £635m of investment committed to 11 projects worth a total of £2.3bn, it's busy enough with the taxpayer money at its disposal.

And the Scottish government has used the opportunity of the conference to press its case for funding of £500m of projects, including greener street lighting.

Electrified fence

Meanwhile, the pressure to break up RBS is coming from various sources - even the Archbishop of Canterbury. With legislation being put in place for an 'electrified ring fence' within the big banks - cutting off risky investment funds from core household and business banking - Vince Cable has gone a bit quieter on his enthusiasm to see RBS ripped apart.

But along with recent talk, from RBS itself, about the time for a sell-off of at least the first tranche of the government's stake, perhaps at a loss, there are other options being considered. One, floated by Lib Dems, is a giveaway of shares to the public.

Another, I hear, is that the sale of government shares could be of bits of RBS, rather than simply tranches of the 81% shareholding. That could look similar to the sale of Direct Line insurance division, which has been required by the European Commission as a condition for RBS's state aid.

But a further division of RBS is unlikely to be rushed, at least until it has completed the complex offloading of 300-plus branches, being renamed Williams & Glyn's, which the commission also told it to shed.

Clydesdale's basics

The other approach to boosting competition in banking is to encourage banks that focus on Britain's nations and regions.

Clydesdale Bank, which operates in northern England as Yorkshire Bank, is this week marking 175 years of doing precisely that, aided by the recent re-opening of its central Glasgow headquarters.

But for all the talk four years ago of Clydesdale seeing out the downturn while its rivals in the Scottish market were hobbled, that hasn't worked out quite as expected either.

On Thursday in Melbourne, its owner, National Australia Bank, published six month figures that showed it's back in the black, but only by shedding a huge and very troubled commercial property loan book.

While Clydesdale reported a £54m profit (contrasing with a loss of £38m in the same October to March period last year), it had bad and doubtful debts of £91m (down from £191m).

Looking more closely at its parent bank's accounts, where those bad loans now sit, that toxic loan book required another write-off of £185m. Although an improvement on last year's equivalent figures within the Clydesdale accounts, that still reminds you that its exposure on commercial property has been a very painful one.

The result is a Clydesdale that's been through a lot of change and pain in recent months.

Morale is not good, as it has worked through 70% of the target 1400 jobs it announced last April it had to shed.

Much of that came from closing down two London offices, leaving only its Piccadilly branch, while it sharply cut the number of its business banking centres in England.

Clydesdale has gone back to basics, boosting its ratio of deposits to lending and expanding its mortgage lending rather faster than the industry as a whole.

And David Thorburn, as boss at Clydesdale, is setting his sights on rejuvenating the brand and its technology, with a £30m mobile banking platform, not least to appeal to a younger demographic of customers than Clydesdale currently has.

One interesting dimension of the problems he's faced is the chorus of criticism from Australia.

With a straight-talking chief executive and even blunter-talking financial commentators, National Australia Bank is seen as being badly damaged by being the only one of the country's big four lenders to have exposure to Europe.

Viewed from Melbourne, any such association with the continent's stalled economy, let alone UK or Scottish banking, is seen as a big black mark for investors Down Under.

- Published1 May 2013