Fifty shades of publishing

- Published

Women over 40 are writing much of the new erotic fiction

I'm off to Edinburgh's Book Festival, as I write. It's 30 years old and the biggest of around 40 such bookfests around Scotland, stretching through the year and from Shetland to Wigtown, Scotland's national book town.

They have been a big success in bringing authors and readers together, and showing the appetite for public debate on the issues tackled in books and beyond.

Making that link is one of the key ways of selling books these days. The once solitary life of an author is now more often on the road, promoting and building audience for the next book.

That's also one of the ways bookshops are fighting off the cut-throat cut-price battle with online retailers. Author events give readers an authentic experience. Bookshops are adding coffee and scones too, from which the margins are rather healthier than for the average paperback these days.

Tricky time

That much I've learned from researching this week's Business Scotland programme.

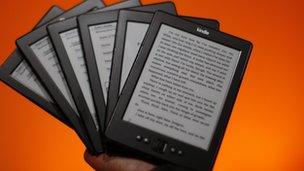

Electronic readers have changed the face of the publishing industry

Bookselling and book publishing are probably the sector that's faced the biggest impact from the challenge of technology.

It was the first one to face the rivalry of Amazon for printed book sales. That was just as the industry came off the "net book agreement", which had long ensured that books in Britain could not be sold for less than the cover price.

Allied to that has been the arrival of the downloaded e-book, in which Amazon has again been a key player, via its Kindle.

Oh yes, and there's been a recession too. It's been a tricky time in the book trade, taking advantage of the opportunities from technology, while facing unprecedented challenges from it.

Boddice-ripper

Demonstrating the opportunities, EL James found, in publishing Fifty Shades of Grey, that you can by-pass reluctant publishers, fire up your boddice-ripper on free or very cheap software, and go straight to the customer.

Her success has spawned a vast number of imitations, many erotic, and many not. Research recently showed these wannabes are mainly women and mainly over 40. Somehow, that much comes as no surprise.

And hearing from Adrian Searle, publisher of Freight Books in Glasgow, a recent start-up that spun out from his graphic design firm, there's a world of difference between those unsolicited offerings by people who have trained in creative writing, and those who have not.

He says there's also a job to be done by such publishers in letting hopeful first-time authors down gently. The job of the publisher is part-psychological counsellor. These manuscripts are not just commodities: they are the stuff of dreams, and of souls.

Adrian, incidentally, argues that new publishers have to be born digital and born global. He defines himself as an English-language publisher rather than a Scottish one.

Currency of quality

So there are more titles than ever being published, even though self-publishing removes the publishers' role in quality control.

And the cheapness of e-books has expanded the number of books being sold, though often very cheaply, with free offers of tantalising opening chapters, or daily deals for well under £1.

That's great for expanding readership. It's not so good for maintaining the currency of quality writing. It's reckoned that only around 4% of published authors actually make their living out of it, and that's getting more difficult as these e-prices plummet.

Phillip Jones, editor of The Bookseller, told me that e-book sales now account for around 20% of the total, though it's a much bigger share of crime, sci-fi and romantic fiction. Erotic fiction is probably over 50% downloaded.

But even with the unpacking of so many tablets and e-readers last Christmas, Jones says the industry's a bit surprised that it hasn't seen as much growth as expected this year in areas where the printed book remains strong; non-fiction, literary fiction and children's.

Finding niches

Indeed, the resilience of printed children's books explains one response from booksellers; attract the kids in, and the parents and grandparents with them might be cajoled into buying something for themselves too.

The two sides of the new technology ledger - opportunity and challenge - also extend to smaller operators finding niches.

Waterstones, the last remaining national book chain, continues to struggle against Amazon, with yet more shop managers being shed. But indie shops can exploit those niches and reach the world.

Adrian Turpin, director of the Wigtown Book Festival, pointed out that the 20 or so book-related businesses in the south-west booktown, don't have to rely on passing trade through the winter months when they can do their second-hand book sales online.

Anyway, I'm nearly in Edinburgh's Waverley station, bracing myself for the Fringe-time assault of leaflet distributors.

I'll leave you to listen to lots more about the publishing industry on the Business Scotland programme, either via BBC iPlayer or by free download.