Scottish independence: Border tensions

- Published

Mr Osborne's North Sea trip coincided with another Treasury paper on Scottish independence

George Osborne doesn't always find himself among friends when he ventures north of the border.

But oil industry executives have grown to like him. They got there by a roundabout route, having been infuriated by his tax raid in the 2011 Budget.

With an impressive lobbying operation, it didn't take long to get the message across to the Treasury that Chancellors mess with the tax regime of the UK Continental Shelf at their peril.

This industry has plenty other places to park its investment, and if there's one thing it loathes a lot more than high tax, it's unstable and unpredictable tax.

George Osborne has learned that lesson the hard way, and 30 months later, the oil and gas industry had him at its Offshore Europe extravaganza in Aberdeen, telling the execs how much he values them, their offshore workers, the tax they pay, their export earnings, innovation, etc etc.

The value of offshore energy was driven home by the latest OECD paper, looking at the UK within the context of developed economies and emerging ones, showing that British investment as a share of GDP is below all the others. This is one industry that's doing its bit.

So eager was Mr Osborne to show he's one of them that he flew off (in a Super Puma helicopter) to a platform in the Montrose field, where the old kit is getting a bracing blast of the big new investment, for which the Chancellor is taking the credit.

His visit had a number of interesting elements to it. One was a full-on rebuttal to the anti-fracking lobby. Local communities should benefit from shale drilling, he said, but he's not going to let Britain lose out on new and potentially cheap energy sources - not with the investment, jobs and lower customer bills that could bring.

Volatility

And then there was Scottish independence. And George Osborne's arrival in Aberdeen came with the publication of another of the Treasury analysis papers of the Scottish economy (if you can see past the propaganda purpose, they're very interesting reading. I'm told there are six to come, one of which tackles immigration. It'll have to be carefully worded.)

The latest one stresses the integration of the Scottish economy with the UK as a whole. Much of it is about the volatility of oil and gas revenue, with a familiar argument that its peaks and troughs can more easily be absorbed into the UK public finances.

It's hard to make that argument without making it sound like the sector doesn't matter that much to Britain. But the thrust of the argument is that Scotland's public spending requires a sustained high level of tax revenue to keep its deficit to a manageable level. In the years when it falls short, there would have to be higher taxes or lower spending. Or more borrowing.

The Treasury follows this up with the argument that it is giving big tax breaks as incentives to the energy industry to invest in getting more from old fields, in reaching new reserves in hard-to-reach places, and in decommissioning.

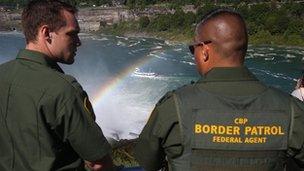

Research suggests Canadians are more likely to trade with each other than with neighbouring US states

It's not obvious why Scotland couldn't offer similar breaks, though it would clearly reduce the tax take to either London or Edinburgh treasuries, in exchange for longer-term tax benefits from extending oil and gas output.

Decommissioning is particularly interesting. It was part of the 2011 tax grab. But after all that lobbying, Mr Osborne has accepted that the industry requires clarity and predictability about how much it's going to cost (and how much the government's going to help) in breaking up all the platforms and pipelines it's been placing offshore.

The bill is put north of £30bn. And with 'the final decommissioning deed' announced in the Aberdeen speech, there's now an unusual £20bn guarantee of tax breaks to ensure it happens.

That helps clarify deal-making involving offshore assets. Without clarity on decommissioning costs, it's much harder to bring new investors into the North Sea.

But now, they're piling in; China and Korea adding to the US, Canadian and Norwegian commitments, and a Japanese energy firm adding to the investments this week.

Tweed and Cheviot effect

I digress. On the independence debate, the latest Treasury paper also offers a detailed analysis of the 'border effects' from making an independent boundary at the Tweed and Cheviots.

This is interesting to economists. It's not quite so clear it helps the state of the debate.

The headline finding is that the average household will be £2,000 worse off in an independent Scotland than it would be if trade, capital and labour flows continued in the United Kingdom as it is.

Behind that headline are some big assumptions. The economic literature looks at neighbours to assess how much they are driven to trade internally rather than across borders.

The most detailed work has been done along the 49th Parallel between the US and Canada. It reflects Canadians' tendency to trade with each other, even at long distance, than to trade short distances across the border with Americans.

One study, from 1995, suggested that Canadian provinces were 20 times more likely to trade with each other than with US states of similar size and proximity.

Despite a common language and similar business culture, a further study went on to suggest that the presence of the border reduces US-Canada trade by 44%.

Patriotic purchases

That doesn't appear to have impoverished Canadians unduly. It may have helped sustain some of their industries, if only through patriotic loyalties. On the other hand, economic theory tells you trade works by shifting production to the location where things can be made or provided most efficiently, so any barriers to trade ought to make countries worse off.

There are, of course, a number of factors that don't carry over to Scotland: Canada and the US have different currencies, they've never had fully free trade, and they've never been in the same political union in the past.

These are big differences with Scotland's relation to the rest of the UK. And the other parallels the Treasury has picked also seem a tad inappropriate to the Scottish nationalist proposition; the creation of two nations out of a highly integrated single state, with a common language, culture, regulatory standards, business law and - for now at least - currency.

The Czech Republic and Slovakia split at a time they were going through a fundamental shift from command to market economy, an opening to trade with western Europe and when their income per head was far adrift. Their currency union barely lasted a month.

Austria and Germany have the same language, but they've only been united under Hitler. They had separate currencies until joining the euro. That is true of most of the eurozone countries - they're about growing together economically from a position of not being integrated.

Ireland's split from British rule was under unhappy circumstances where income per head was very different, and where the Irish imposed protectionist measures. Despite a free trade agreement since 1965, the more recent story of the Irish economy is about replacing its dependence on trade with the UK with an opening to the European Union as part of the eurozone - a trend which Scottish nationalists wouldn't mind repeating.

In short, there are assumptions built into this economic modelling by the Treasury which require a dose of freely traded salt.