Lessons from the Battle of Grangemouth

- Published

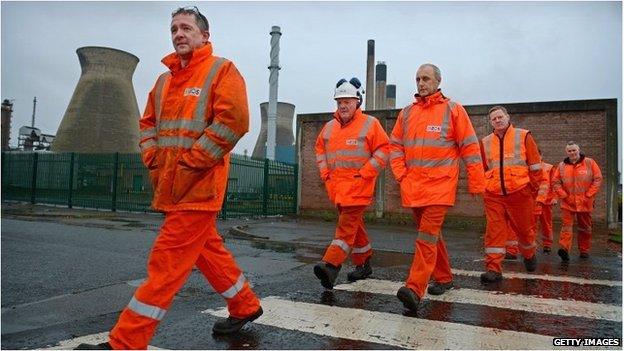

The Grangemouth dispute moved quickly over the past two weeks

Well, it's been a white-knuckle ride for Grangemouth and anyone who cares about the Scottish economy.

Only one of the surprising parts of this story is how fast it moved. Disputes like this usually take many weeks to unfold. But having come to the boil only two weeks ago, this one had dramatic tension and pace and was over before the weekend credits rolled.

Who won? Well, of course, Grangemouth did, and its workers and the wider Scottish economy. Politicians showed they can put differences aside to act as peacemakers.

Jim Ratcliffe founded Ineos 15 years ago

Jim Ratcliffe and Ineos emerged from relative obscurity to become poster boys for global capital. The firm secured a bundle of sweeteners from governments, BP (easing the terms of its supply contract) and, of course, from workers.

And who lost? Workers made sacrifices on pay and more so on pensions, but the humbling was for their union, Unite.

Red top notoriety

The employers had asked for a no-strike deal for two months. What they got was three years, along with everything they sought on pay and pensions.

The union lost all that, when it hadn't even fought over it. Instead, it chose to make a stand on a disciplinary matter, letting it become entangled with much wider demands from employers, then rushing calamitously into provoking the shut-down with a strike date.

The disciplinary issue, affecting union convener Stephen Deans, still isn't resolved, though it was due to be completed on Friday.

But it's worth noting the Ineos 'survival plan' was firmed up to ensure that the Grangemouth complex will have no further full-time union conveners.

Despite his red-top notoriety, Jim Ratcliffe claims not to be anti-union. He told the BBC he sees a role for them in representing workers, and in working with management on investment options and maintenance programmes, while sharing the common aim of the company's success.

He claims to get on fine with unions elsewhere. Indeed, he's got a similar investment project under way in Norway, where little moves in the oil and gas sector without union consultation.

Carrots without sticks

For other unions, and on other sites, co-operation has become more of the norm, for instance finding common cause on training and safety. Workers and bosses have worked together to steer a path through the downturn, where sacrifices have been made to secure jobs, retain skills and minimise compulsory redundancies.

It will be interesting to see if that unravels when the fruits of recovery are there to be shared out, or if lessons have been learned that can be carried over from the co-operative downturn years.

It might be more likely to do so if these relationships existed within one country. But the Ineos case is a reminder of how a modern corporation can work; behind veils of secrecy about its affairs and finances, without accountability, and with global investment portfolios allowing it to play off one plant against another.

As Unite has learned the hard way, there's little a trade union can do about that. And as governments have found, they can offer carrots to attract international investors, but the modern economy offers them few sticks. Carrots were duly deployed in this case.

Near death experience

Perhaps the main lesson to learn from this is the need to think and plan ahead. Several commentators have reflected on this.

For unions, there's a need to see the context in which their sector works, and to see ahead to the direction their employers are heading. Change is a constant, so it's doubtful that digging in to defend the past is much of a long-term strategy.

For government too, the near-death experience of Grangemouth petro-chemical plant brings up questions of what it can do to constrain or harness the power corporations have over strategic assets.

It also raises the question of how governments can plan ahead as industries rise and fall. That helps inform the skills and infrastructure that government puts in place, and where it puts seed and development funding where markets won't.

For 49 hours between Wednesday and Friday, the threat to Grangemouth prompted Scotland to face up to a future without the business of producing and processing hydrocarbons.

This has taught us a lot about the refining and chemicals industry, just one facet being the threat across Europe from efficient competition in other parts of the world.

The Scottish chemicals consortium responded to the Grangemouth turnaround with a welcome, but also a warning - that the competitive advantage it gets from re-orienting itself to the processing of shale gas from the US also protects it from the looming 'bloodbath' across the European sector.

Even if Grangemouth has now secured its future for 25 years, it may already be time to ask; what comes next?

Business Scotland this weekend considers the lessons of the dispute at Grangemouth. BBC Radio Scotland on Sunday at 10:00. It will also be a feature of Sunday Politics from 11:45 to 13:00.

- Published26 October 2013

- Published25 October 2013