Seismic plans to tackle North Sea failings

- Published

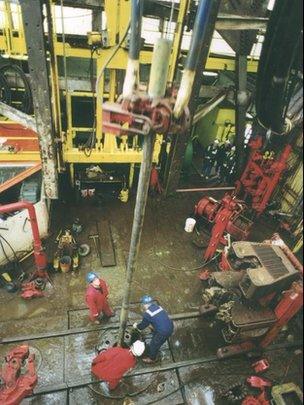

The cost of producing the average barrel has risen five-fold in a decade

There's something impressive about the engineer's mind - it focuses on identifying a challenge, finding a practical solution, and telling it to you straight.

That's particularly true of the oil and gas industry. And that's the approach behind the report published on Monday by Sir Ian Wood, pre-eminent figure of Aberdeen's oil years.

His analysis of the industry's failures, shortcomings and short-termism is blistering. He isn't much kinder to the civil servants who have regulated the industry for more than 40 years.

And his recommendations represent a major shift of power from both of them - creating a new, arm's-length regulator, with big sticks more than carrots, to name and shame poor performers, and ultimately to force a sale of assets.

This analysis spells out the end to an assumption that the UK public interest was aligned with that of the private oil companies. Until now, the policy has been: hand out licences, they drill, they pump, they make profits, they're taxed, and everyone wins.

Not any more. This report reflects a new reality - that the interests of private companies may no longer be aligned with the public interest. So on behalf of the public, it argues the government needs to step in.

Tax grab

Sir Ian was asked by Whitehall's Department of Energy and Climate Change, in response to an alarming and unexpected 38% fall in production over only three years.

The UK government is particularly alarmed that such a fall has cost it around £6bn in foregone tax take.

On that tax point, it's worth noting that Sir Ian's terms of reference did not let him look into the impact on reduced investment and production that resulted from the Treasury's £2bn tax grab in the 2011 budget.

This is only pointed out in an appendix, though it's added that the fiscal regime "featured heavily" in interviews with oil industry players.

No surprise there. The industry was infuriated, and this report lists the efforts made by the Treasury and DECC to win back the industry with targeted tax breaks.

'Not adequate'

The first of two strikingly blunt messages in Sir Ian's report is that the current regime for the UK's offshore oil and gas sector is simply "not adequate".

What's gone wrong? The cost of producing the average barrel has risen five-fold in a decade. The number of fields has risen from 90 to 300, the average one producing far less than the monster production of the Brent and Forties heyday. And there's been a 50% rise in the number of operators, complicating things further.

Operating assets are showing their age. And while technology is allowing for extraction from tight rock and high-pressure, high-temperature reserves, it comes at a cost which companies are reluctant to pay.

"There are strong signs that under-investment (in those technologies) will have a significantly adverse effect on maximising economic recovery for the UK," writes Sir Ian.

This reflects a much more complex offshore sector than the 1970s, when this regime was put in place. DECC is described as being "significantly under-resourced, and far too thinly spread to respond effectively to many of the demands of managing an increasingly complex business and operating environment". In other words, the department is out of its depth.

Short-term horizons

The other strand of recommendations represents that power grab, both from commercial operators and from Whitehall civil servants.

This is radical stuff. Companies are being told they will have a duty to act in the national interest of maximising recovery of oil and gas, even if that clashes with their perceived commercial interest. (Which nation's interest? I'll return to that.)

The drop in production is seen is "unacceptable and illustrates the shortcomings of existing asset stewardship".

So under the Wood plan, companies would be held to account by a much stronger and better resourced regulator, at arm's length from government.

If they are deemed to be under-performing, they'd get a private warning, then a public one, and ultimately, the regulator should "encourage the sale and transfer of assets to a company more committed to maximising economic recovery".

On the evidence shown, that would cover several of the companies currently operating in UK waters.

Sir Ian says: "In many cases, it appears that companies have constrained asset investment and expenditure in a drive to deliver short-term returns."

Where companies are in consortia for sharing pipelines and other assets: "The frequency of failure to agree between and within consortia on key issues, including access to infrastructure and development of field clusters is very damaging."

For instance, west of Shetland, the new frontier that's vital to the future of the industry, has had lots of talk, but "little collaboration has yet been achieved in field and infrastructure development".

That infrastructure - both maintaining old kit and investing in the new - is the "Achilles' heel" of the industry. So where joint ventures are failing to get on and invest, Sir Ian wants to put the regulator into the decision-making room with them, to knock heads together.

Sir Ian Wood wants the industry to hand over data, without lengthy delays. It should also be able to publicise how well companies are doing in looking after the asset they've been handed under the block licence system.

And while he's at it, he wants this regulator to apply its powers and rigour to the onshore potential for shale and fracking.

More confrontation

What this points towards is an explicit recognition that the oil and gas producers no longer share (if they ever did) the interests of the UK in maximising output.

Each investment decision is weighed up against alternative prospects in more attractive basins around the world.

And as extraction costs per barrel soar, it gets harder to justify spending in UK waters.

There's still a big appetite for investment. The UK offshore sector is seeing record investment this year. But that's expected to come down off its peak very soon, and surely won't last if costs continue to climb.

So if you assume the UK has an economic interest in squeezing as much as possible out of its sub-sea reserves (and the environment lobby would stop me there to point out that it has no such interest), then it's going to have to be much tougher and perhaps more confrontational with the producers on whom UK plc depend.

Would Holyrood do better?

What, then, of Scotland plc, and the nationalist case for taking over control of these reserves?

I could find no mention of the independence debate in Sir Ian Wood's paper, just as I have heard little critique from nationalists of the way the Whitehall licensing regime has operated (as opposed to the tax regime).

But all the same issues would apply to an independent Scotland. It could be an opportunity to set up more robust regulation, if Whitehall flunks Sir Ian's test.

But ask yourself this question: would Scotland be in a better negotiating position to make demands of the offshore producers, or would they need them even more than Whitehall continues to do?