Shared tax powers: a tricky balancing act

- Published

The arrival in Edinburgh of the men from the International Monetary Fund was one of the scary prospects offered up last year by critics of independence.

The 'no' majority hasn't kept them at bay.

I met one of them at Edinburgh University earlier this month.

To be clear, Carlo Cottarelli wasn't there to impose draconian conditions to a bail-out of Scotland's finances. Nor was he speaking on behalf of the IMF.

He was invited to explain how taxation and spending works in federal countries, having recently co-authored a study of 13 nation states where 'sub-national regions' have extensive powers - as with the American, Australian and Indian states, Canadian provinces and German lander.

They looked also at Austria and Spain, which aren't quite federal systems, but have elements of sharing taxation and government spending from which it's worth learning.

Smith Commission

And while this academic tome was directed towards informing the hugely complex question of how the eurozone can co-ordinate its governments' finances better, it's not hard to see the implications for future fiscal relations between Holyrood and Westminster, if the Smith Commission is to be enacted.

Or rather, a close reading of it might indicate that there are bits of the Smith Commission, external that might be better not enacted, or at least re-thought, at a more careful pace.

The book, Designing a European Fiscal Union, published by Routledge, £88, takes some digesting.

For a more readable (and cheaper) guide to devolved tax, external, the Scottish Parliament's research service, SPICE, is worth a look.

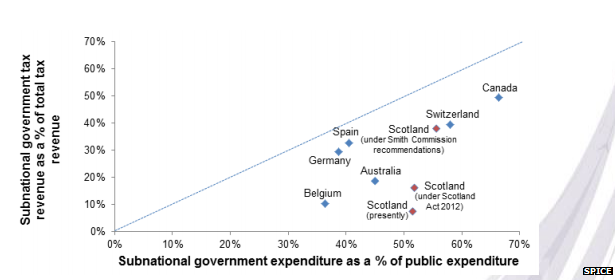

It helps to put the changing position of Scotland's tax autonomy into some international perspective.

The conclusion of the IMF study is that there is no one way to skin the federal cat.

The share of tax raised by 'sub-national' regions ranges from 31% in Austria to 67% in Canada. Germany is at 39%; the USA at 60%.

But if you take out shared taxes, over which the sub-national region has limited control, the picture is different. Only Canada, the US and Switzerland are above a third. In Austria, Germany and Mexico, it's under 10%.

The study calculates a transfer dependency, a measure of how much sharing and pooling of resources goes on within each country, and that also ranges widely.

It accounts for 88% of regional spend in Mexico, 16% in Canada, and 18% in the US. Among countries more similar to the UK, figures include Austria 45%, Belgium 64%, Germany 54% and Spain 50%.

Recommendations were made by members of the Smith Commission

The IMF economists show that systems are, of course, shaped by the history of how countries were drawn together.

They can be changed - as is the case with the eurozone - by the often bruising experience of shocks for which their rules were not prepared.

And they depend on one commodity that is not immediately evident from the current state of Holyrood-Westminster relations: a mutual desire for co-operation and stability. That is, you can get systems that work, but all sides have to buy into them and must want to make them work.

Deficit and debt

What these arrangements require are fiscal rules, recognised by both sides. The obvious ones are around the scale of deficits and debts.

And if two governments have a different approach to taxing, spending and cutting their way out of recession - as between the Westminster coalition and the Scottish government in recent years - then there's an obvious problem.

For those who break the rules, there have to be meaningful sanctions. And as the eurozone has found (it didn't take a genius to see this problem coming), countries that run rule-breaking deficits are not well placed to pay big fines as a penalty for doing so - not without borrowing more and running a bigger deficit.

Achieving flexibility and consistency is a tricky balancing act. Co-ordinating across the economic cycle, and applying that famous economic stabiliser, requires thinking in advance of the point when the downturn hits home.

There's a long history of ad hoc arrangements being put in place when there are such crises. Together, they offer some worthwhile lessons for those trying to plan ahead for a robust system.

And there's borrowing: when should it be allowed, to what extent, by what means, who carries the risk, how much should a central government signal its willingness or unwillingness to leave its smaller partner hanging out to dry in the bond markets?

A crucial part of any federal system is the extent to which it shares risks and transfers money from the rich to the poor, from the buoyant to those fallen on relatively harder times.

All of these issues require inter-government bodies to negotiate the share-out of powers, inter-government grants, the application of rules and borrowing quotas. Both or all sides have to be politically committed to these bodies.

What works?

We're yet to see the machinery that the UK Treasury sets up which gives devolved administrations some parity of esteem in such negotiations, as the IMF indicate you ought to be able to find in Belgium, Mexico, Argentina and the USA.

That will, or would, be a big challenge to the culture and the sovereign will of Treasury ministers and mandarins. The Barnett Formula has, for 36 years, been a way of avoiding such discussions.

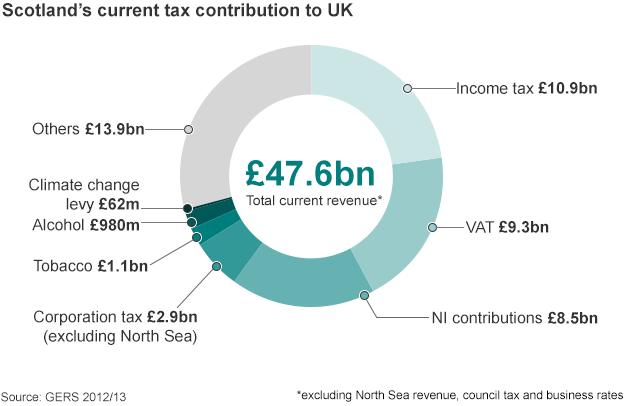

The IMF survey found that the answer is typically through income tax. And that is a bit of a problem, because income tax is the main pillar on which the Smith Commission built its further devolution of powers to Holyrood.

If the Scottish Parliament is to depend on buoyant income tax take, it is going to have to have very much sounder data on which to base its forecasting.

And that income tax departure from the federalised norm is a reminder that the Smith Commission seems to be based on very little assessment of what doesn't work elsewhere, before committing to what it thinks will work.

This may become clearer today as we get the draft clauses of the legislation being built on the Smith Commission foundations.

No detriment

One aspect of those plans that grabbed the attention of academics discussing the IMF study with Sr Cottarelli is something called the 'no detriment' principle. It's significant because the expert in these federal systems knew of no other country which has it.

It's in the Smith Commission report, page nine, section seven, subsection five, and it goes like this: "The package of powers agreed through the Smith Commission process, when taken together, should not cause detriment to the UK as a whole nor to any of its constituent parts".

It goes on to say the further devolution should cause "neither the UK Government nor the Scottish Government to gain or lose financially simply as a consequence of devolving a specific power".

I'm hazarding a guess that you'll probably hear more about this, because if it's interpreted literally, it means that the use of any tax power which gets an advantage over another part of the UK requires compensation to the disadvantaged side.

Whatever one side gains, to the disadvantage of the other, it has to refund.

That looks fiendishly difficult to calculate in a way that either side of such negotiations could agree upon, as the impact could be felt over many years.

Stamp duty

And whether it's designed to look this way or not, the implication is that a lot of policy divergence would be rendered pointless. And if you can't diverge policy to make a difference, why bother having the power?

Indeed, this problem is already being seen in the assumptions being made about the devolution of stamp duty to Holyrood, and the impact that has on the Scottish block grant.

We've seen problems and anomalies arise around this sort of thing before - for instance, when the funding of English students diverged from Scotland's, when water boards were privatised but not in Scotland, and when free personal care in Scotland didn't align with the UK-wide attendance allowance.

To return to the debate before 18 September 2014, would independence avoid such difficult circumstances? Possibly. But remember the need for negotiations to share the pound sterling as the continuing currency for Scotland?

A lot of the challenges facing federal systems would crop up in these talks too. The book is, after all, about the choices facing independent countries which share the euro.