The drill bill bites

- Published

Let's start with the good news for Britain's oil and gas industry. This won't take long.

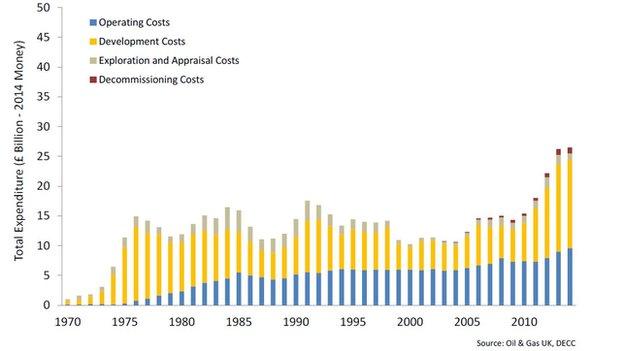

Last year saw a record level of investment. At £14.8bn, that's something to celebrate, isn't it?

Less good news is that it rose from 2013 because of slippage in projects and cost over-runs.

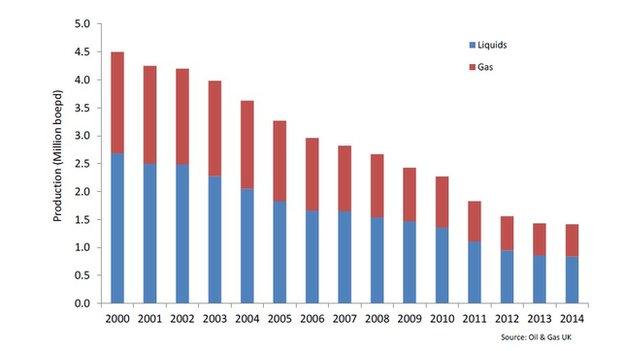

But we're not finished with the happy tidings yet. No. The decline in production has been getting much less steep.

After reducing by an alarming 19%, 14% and 8% over the previous three years, it was only 1% down during last year.

Due to several years of big investment, 2015 should see the first rise in production since the peak 15 years ago, but only by 1%. It's on track to stay around that level through the rest of this decade.

There's one more bit of good news, at least if you're in the business of breaking up oil platforms, or you are of the green persuasion and wish to see as much oil as possible kept under the seabed.

Activity in the decommissioning sector was up more than expected. It's due to reach £1.8bn per year through the rest of this decade, and probably more if offshore operators plug old, unprofitable wells earlier than previously planned.

Indeed, we've got a new estimate of the total cost of decommissioning up to 2040.

It's up from last year's estimate of £41bn to £46bn in today's money. That's a lot of cost for oil producers. It's a lot of opportunity for the scrapping sector.

Much of the good news reflects a second wind for the North Sea, with high investment to squeeze more out of a mature area, and big new prospects being developed west of Shetland (a quarter of the total investment last year).

But much of the worse news from this year's Oil & Gas UK Activity Report reflects the plummet in the oil price. This is the best guide to what offshore operators have been doing and plan to do, in a business where they otherwise prefer to keep a lot secret.

Much of the information collecting of those plans was done towards the end of the year, when the oil price was still around $75 per barrel. So it doesn't capture the full extent of the slashing of operating costs, investment and, above all, drilling.

Costs up

Costs have been heading rapidly in the wrong direction. The total was up 8% last year, to £9.6bn. And that was despite efforts to bring down costs even before the oil price sank.

Next month's Budget is likely to include some tax concessions

In 2012, the vital measure of the cost of producing the average barrel was £13.50. With costs up and production down, it was up to £17 within a year. Last year, it hit £18.50.

In the northern North Sea, where the big old fields have depleted most, but platforms still require expensive maintenance, the average operating cost has soared to £27.

To retain a sustainable sector, bosses say costs will have to come down by at least 20% and perhaps as much as 40%.

According to Malcolm Webb, chief executive of Oil & Gas UK, the one upside of the sub-$60 barrel is that it's left no alternative but to cut costs and inefficiency.

As that involves downward pressure on contractor rates and a change to rotas - longer turnarounds reducing helicopter transfer costs - the industry's got an industrial relations battle on its hands.

Because of the dire figures throughout this report, workers' bargaining power is weakened, and managers are better placed to win.

Other areas where the industry wants to cut costs include more co-operation between operators on logistics, transport, support vessels, crewing and contractor rates.

Investment falling

While investment hit its record £14.8bn, we know that more has been given the green light for the years ahead.

But there are sharp falls ahead, down to £11bn at most this year, and £8bn next year. If there are no more commitments made in the next year or so, with uncertainty continuing around the oil price, investment will hit only £2.5bn by 2018.

Revenues, meanwhile, were £24.4bn last year. So the outflow of cash - along with tax, totalling £29.7bn - was a long way north of the inflow.

It hasn't looked that way since the industry was pouring money into platform fabrication yards in the 1970s, ahead of the oil and revenue taps being fully turned on from 1980.

Next year, unless something radical happens to costs, it's going to look a lot worse, because projected revenue looks like £17bn.

Wells sink

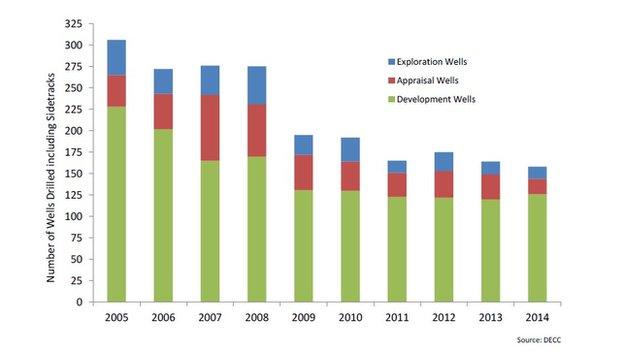

What, then, of drilling? Without that, there's not much future for the industry, other than seeing it run down. The cost of exploration has soared, partly because the complexity of targeting high-temperature, high-pressure or deep-water reservoirs is greater than it was.

While there has been a sharp decline in the number of wells drilled over recent years, those that have been drilled have had a poor success rate.

Put those factors together, and the cost of finding the average barrel of oil has risen from £4 in 2009-11 to £22 since then. And with only 50 million viable barrels found last year - just over a month's production at current flow rates - that's a long way short of replacing the reserves which are depleting elsewhere.

This is not just about a fall in exploration. The next phases of appraisal and then development well drilling have been declining as well.

Lower taxes

In total, there are around half the number of wells being drilled than there were 10 years ago. With the oil price so low, the number of planned exploratory wells is down this year to between eight and 13, with appraisals below five.

The industry message to government is to call for smarter regulation and lower taxes, in line with Sir Ian Wood's industry review last year.

A new regulator is being put in place, bringing more expertise and focus than the Department of Energy and Climate Change has given the offshore industry.

And it's a racing certainty that the Budget next month will see some concessions in an attempt to boost investment and to support the industry.

Without much profit, reduced tax can't make that much difference. Profits look very weak, in the short term at least. Lowered tax can only be about building industry confidence for subsequent years.

- Published24 February 2015