Scotland's shifting media landscape

- Published

Newspapers have been notoriously poor at adapting to a hugely disrupted market.

They can handle competitors. They've adjusted to radio and TV. But few saw what the internet would do to them.

Having worked in newspapers for nearly 20 years, my take on it is that they were too often run by people whose main qualification was the ability to hit an advertising target, without the imagination to foresee and adapt to technological change.

And so we learned last week that the decline in newspaper print sales continued its last year.

It could have been worse. Interest in the independence referendum may have stemmed the decline a bit.

But when you note that the Daily Record and Sunday Mail saw their sales fall more than any other "national" (mostly London-based) daily and weekly titles, then it doesn't look reassuring for an industry which has been one of the pillars of Scottish national and economic identity.

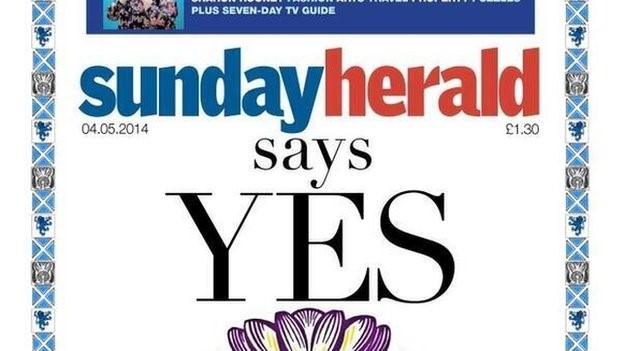

The headline-grabbing story was that the Sunday Herald had seen its circulation rise 35%. There can't be much doubt that it was a response to backing a "Yes" vote.

But at an 32,000 average sale, it's a reminder that the Herald's weekly stablemate had fallen precipitously before the turnaround. And it's a long way from reaching the 1.6m who voted "Yes".

Nor has The National done so. Launched in November by the Herald stable, the latest industry intel is that the title is selling below 20,000 a day [since writing, I've been informed that paid subscriptions are around 17,000, but they're not saying what total sales are. We'll know more next August, with the next set of industry figures].

Niche papers

However, what The National demonstrates is that newspapers can innovate, and can seek out market niches, without needing significant extra overheads or staffing.

It is for those who want their news with a heavy pro-independence slant. Even the crossword clues are on message: "21 Down: Sly UK deal makes us huffy (5)".

And the publicity, easily reaching the cause's true believers, saved the Herald group from having to do much marketing.

There are near daily innovations in the market. While conventional journalist jobs have been lost, the Daily Record is now advertising for a new team of online journalists. They are younger, cheaper and, as digital natives, easily slot into online, mobile, app and video requirements.

The Record's Mirror Group stablemate is doing something similar in Northern Ireland, with a low-cost news operation to take on the Belfast Telegraph.

The Times is putting effort into an Irish digital edition. And also in Dublin, Rupert Murdoch (whatever you think of him, he's shown a lot more foresight than most) has bought Storyful, a news service driven by social media. He has put the famously innocent Rebekah Brooks in charge.

Wanted: A new Taggart

Across the Clyde from the Record office, at STV headquarters, they are following a plan to handle the disruption to the television market from the explosion of channel choice.

The company had some rocky times in responding to market and technological disruption, and fell into a dispute with the dominant Channel 3 programmer, ITV.

But chief executive Rob Woodward has put that in the past. He's stabilised the company, rewarded shareholders with a big lift in dividend, and he's driving the digital business as the company's main future.

STV has also opted to innovate with city TV stations.

The broadcaster is working alongside university journalism students to produce stations for Glasgow and now Edinburgh. It's applied for other city licences in Scotland.

There's not much evidence of impressive viewing figures for these city stations so far. The flagship city shows - Riverside and Fountainbridge - have been shortened, while longer on-air hours are filled by archive material.

The other part of STV's turnaround strategy is to build up commissions for other broadcasters. Game shows and antiques programmes are doing OK, but total sales are down. It lacks a replacement for the murderous, long-running Taggart success story.

Privileged funds

Just along the south bank of the Clyde, the BBC has been one of those new customers of STV productions, despite being the commercial broadcaster's main rival for TV audiences.

Both are converging into the newspaper market for news, which makes relationships across the media a bit tense at times.

The BBC is seen as privileged to have its funding from the licence fee, while others have had to cope with market disruption.

I have to declare an obvious interest here, and acknowledge what a privilege that funding stream is.

But the BBC faces a different type of challenge, both from technology and from the political environment within which the corporation has to operate.

As the pace heats up towards the next Royal Charter, by which the BBC is steered every 10 years from Whitehall, a lot is at stake; what the BBC does, what it doesn't do, how it relates to its commercial rivals, and how it is funded, governed and held accountable.

iPlaying dodgers

The licence fee would be hard to introduce now. And for a young generation, increasing numbers choose to dodge it - accessing broadcast through various devices other than a television, and using only the catch-up services offered, for free, by the main broadcasters.

The director general, Tony Hall, this week set out his case for a Charter renewal that doesn't hobble the organisation. His speech made the case against the gradual erosion of the BBC, saying that sleepwalking into decline would leave Britain diminished, and open to global corporations to clean up.

That speech follows on a particularly significant report, external from the Commons Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport.

The recommendation that got the headlines was the committee's observation that the licence fee is getting harder to justify. Also that the BBC Trust needs to be scrapped and replaced by a new governance system.

Examples cited as potential replacements for the the licence fee included Germany - a flat household levy with exemptions for low income - and Finland, where the levy is income based on the individual rather than the household, up to a maximum. Rather than the cumbersome collection system, it's suggested the fee could be paid with council tax or utility bills.

Something for everyone

Cutting across the idea of a universal payment is a challenge to the BBC's aim of providing a universal service.

The MPs had this to say: "The BBC must make the most effective use of licence fee payers' money and should not be trying to do everything itself.

"The BBC needs to be able to make bigger, braver decisions on its strategy and inevitably must do less in some areas.

"Similarly, we challenge the BBC's justification for doing all that it currently does in order to provide 'something for everyone'."

Yet if not aiming to offer something for everyone, isn't it hard to make the case that everyone should fork out?

BBC News, from STV?

In a long report, there were quite a few other ideas that will come into the Charter Renewal debate. And given the BBC's reach, these could shape much of the rest of the media landscape.

MPs were keen to ensure that the BBC does not squash its commercial rivals, instead proposing ways in which it could support them.

Offering free video reports for embedding on newspapers' websites, is one proposal.

Or setting up an independent court reporting network, filing stories for all outlets. (A lack of newspaper resources for reporting from court on wrong-doers means that justice is not seen to be done.)

MPs believe the BBC should be more careful to attribute newspapers' exclusive stories, when the broadcaster follows them up (not that BBC interviews are routinely credited in newspapers).

And it is suggested that a quarter of the news budget could be spent on independent producers, as is the case with other programming.

STV or even rival newspaper groups making Reporting Scotland, or supplying video reports into it? That would be quite a challenge to BBC journalism, and perhaps to the trust of audiences.

The report reflected a rise in programme-making spend in Scotland, as well as Wales - a response to criticism that spend was well below population share.

And while resources and staff have moved from London to Salford, eastern England and the Midlands are notable for being by-passed. With 25% of the UK population, they get merely 2.5% of the spend.

Holyrood questions

The only evidence to the Commons inquiry from a significant Scottish voice was from the Scottish Newspaper Society, criticising the BBC for trampling into local news and distorting commercial markets. It cited Orkney and Shetland as examples.

There was no discussion in this long report of how the corporation could be made accountable to devolved institutions.

Yet the Smith Commission has prepared the ground for the BBC to have to report annually to the Scottish Parliament, and to be questioned by MSPs on its service to Scottish audiences.

That's a long way from the Scottish Broadcasting Service, proposed by the Scottish government as part of its independence plan. It's also far short of devolving control of broadcasting.

But it could be a new challenge and shift of accountability focus, in a media sector which already faces plenty of other changes and challenges.

- Published2 March 2015

- Published25 February 2015

- Published26 February 2015