Energy burners take the high road

- Published

It's obvious. If the oil price falls, oil users gain, and oil producers lose out.

Scotland has plenty people work in oil production, and its supply chain. It has more people who don't. Or at least, more of the economy buys oil than sells it.

So perhaps it's equally obvious that an oil price cut is a help to the economy.

But that's not what the governor of the Bank of England thinks. Mark Carney recently observed that the UK economy would be helped by the (roughly) halving in the price of oil, and the Scottish economy hurt.

But now, we've got the Fraser of Allander Institute's take on the impact of the oil price on the Scottish economy, and it politely disagrees with the governor.

Lop-sided?

Yes, 40 years since the Institute started its regular take on the state and future of Scotland's economic performance, these Strathclyde University economic modellers had an upbeat message this month.

This was hedged about with a whole lot of health warnings on the data. But on balance, it is reckoned that the Scottish economy will be helped with an extra 0.25% growth as a result of the oil price cut.

That translates (the report offers up the word "crudely") into nearly 10,000 extra jobs, at the more optimistic end of projections. At the pessimistic end, there could be 600 fewer.

But of course, it would be regionally lop-sided.

At PwC, which works with the Fraser of Allander, tax partner David Glen reports clients throughout the oil industry supply chain are feeling a squeeze on its way.

It's common to cut some costs and prepare for worse, but to hang on to staff for now, in the hope that the uptick in prices in the past month could be sustained.

Dispersed workers

Thus, the stimulus from lower oil prices is instant - obviously, at the petrol pump, but more widely, as people find the 15% of the economy's spend on energy is leaving a bit of change left over.

However, any downturn in the oil industry could take a few months, or even years, to feed through. While new investment plans are being postponed, approved investment plans are usually going ahead.

Does that mean a slow-burn nightmare for the north-east and happy days elsewhere?

Not as much as you might think. This report points out that the wage impact of offshore oil and gas is widely spread, as any regular user of a train to or from Aberdeen will know.

It cites Oil & Gas UK figures from 2013, showing that 28% of offshore workers lived in north-east Scotland, and 21% in the rest of Scotland. So more than half lived outside Scotland, with 16% of the total in north-east England.

Lighter green

What is harder to forecast are the knock-on effects for decommissioning of old oil platforms. That could be brought forward, meaning a help for the economy.

Neither can we tell what will happen to renewables. Cheaper fossil fuels makes investment in green options relatively unattractive, when most were already commercially unviable.

In other words, you might want to put off buying that electric car or biomass burner.

But then, the drive to renewables may not be fuelled by relative price. More significant would seem to be regulation and consumer choice, according to environmental taste.

Last year's forecast

This assessment of the oil sector adds to the upbeat message that the recovery is gaining a bit of pace. That's not to say the economy will grow faster this year - only that it will grow by more than Fraser of Allander forecast last November.

David Glen points to manufacturing, construction and business services as providing that momentum, while oil and gas drag on it.

So the forecast for last year (bizarrely, we're still forecasting last year, because we don't have data for the final quarter), is up from 2.7 to 2.8%.

Growth this year is projected to rise by 2.6% (it looked like 2.2% in November). That's the same growth rate as the average forecast for the UK as a whole.

And next year, the economy is forecast to grow 2.4% (2.1% in November), which is one small notch above the average estimate for the UK.

Jobs growth has been outstripping economic growth, which sounds great - until you realise that it means productivity isn't improving, so real wages don't stand much chance of going up either.

This year, Team Fraser has a mid-range estimate of 51,000 more jobs in the Scottish economy, taking the unemployment rate to 5% (137,000 seeking work), and 58,000 net growth next year, with unemployment at 4.6%.

Austerity critic

It need hardly be said that there are warnings of what might knock this off course. This isn't called "the dismal science" for nothing.

A Greek exit from the eurozone could be felt over here, on the other side of the European Union, with thousands of job losses.

A further squeeze on government spending after the Westminster election could hamper recovery.

Alex Salmond was co-author of a Fraser of Allander report on the oil industry in 1986

Current coalition government plans imply that the private sector would have to grow at 4% per year to make up for the contraction of government activity, and that doesn't look likely.

So says Professor Brian Ashcroft, who oversees the Fraser of Allander forecast. He is a critic of "austerity", whether real or intended.

He argues that the downturn and low interest rates make this a time for a big government stimulus, with lots of capacity to pile up more debt before constraints kick in.

He also points out that the growth we're seeing is built on a return to investing ways by business (good) and continued growth in household debt (not good). It was already far too high before the crunch came.

What goes around

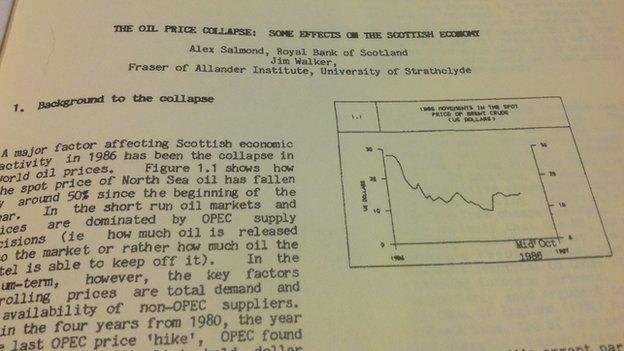

We have, of course, been here before. Oil prices have fallen sharply, and economists have tried to calculate the impact.

Fraser of Allander's commentaries are being digitised, to mark their first 40 years. And in going back, they've looked at what was being written in November 1986.

The oil price had fallen by half that year. Arab producers, through the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries, were choking off the incentive for development of rival high-cost oil fields such as the North Sea. But unlike today, Britain was producing twice as much oil as it needed.

Contrary to this month's report, it was reckoned by the Fraser of Allander authors that the oil price fall would push up Scotland's (already high) unemployment rate by between 0.9% and 1.3%.

The commentary authors said that any government action to stimulate oil industry activity would be "unambiguously welcomed" in Scotland - change in the tax regime, or even colluding with other oil exporters to push the price back up.

Government action was limited, however. And that's one reason why the oil sector workers of Banff and Buchan, six months after its publication, chose to replace their Conservative MP with a guest co-author of that analysis.

He was a Royal Bank of Scotland oil economist called Alex Salmond.

- Published4 March 2015