Drilling for votes, distilling the recovery

- Published

The oil industry got what it wanted from George Osborne's pre-election Budget, and a bit more. So will it work?

Well, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) says the tax cut of £1.3bn should lead to a 15% boost to production by the end of this decade. That's after a steep fall in recent years levelled out last year.

It reckons on £300m more capital expenditure in each of the next three years.

One criticism of the new package was that not enough is being done for exploration. What was included was £20m government funding for seismic surveying of the seabed, providing the sub-surface maps to guide the drillers.

Two problems with that: £20m doesn't go far in seismic surveying, and the areas chosen could look like unfair advantage to those who own those block licences.

Exploration

Anyway, that is seen by the OBR as helping to stimulate another £300m in exploration expenditure over each of the next three years.

Oil & Gas UK, representing the industry, puts it differently: in the near term, £4bn more investment as a result of the tax reduction, and 500m additional barrels of oil or its equivalent.

It also admits that it has to play its own part in getting costs down - a point reinforced by the new Aberdeen-based regulator, the Oil and Gas Authority.

The unexpected element in the Chancellor's package was a cut in Petroleum Revenue Tax (PRT). That is paid on fields that were approved before 1993. At a marginal rate of 82% of profits, it has brought in between £900m and £2.5bn in recent years.

According to Wood Mackenzie, the Edinburgh energy data analysts, around 50 of 328 on-stream fields are covered by PRT, for which this is now the lowest rate since the 1970s.

Swingeing cut

To cut a headline tax rate by a whopping one-third - in the case of the Supplementary Charge on newer fields - looks unusually generous in the current fiscal climate.

It looks less generous when it's added to corporation tax, which runs at 30% of profits while other industries pay 20%. And it's less generous still, when you recall that the cut in supplementary charge from 30% to 20% precisely reverses the increase George Osborne announced in his 2011 Budget - to oil industry consternation.

It's worth noting also, in passing, that in a Budget dedicated to getting Conservatives re-elected, it's odd that the chief beneficiaries will be international oil majors who own assets in the UK continental shelf. That includes the state-owned oil corporations of Qatar, China and Korea, with major stakes held by the governments of Norway and France too.

But these are unusual times for the industry. As we should all be aware by now, production has fallen fast, and the oil price has fallen faster.

So profits are hard to find, let alone to tax. That's why a swingeing cut in the headline rate won't cause the Treasury much pain. This was a Budget which spelled the end to the 40-year era of oil and gas being a government cash cow.

Fiscal autonomy

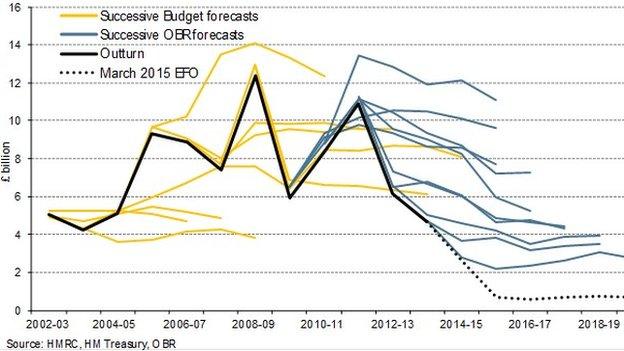

Indeed, after taking into account this Budget's package of tax cuts, the tax take expected by the OBR is sharply down. Really sharply down.

Over the past six years - the period on which the Scottish government chooses to focus - the average tax from UK offshore oil and gas has been £8.1bn. It's varied between £12.4bn and £4.7bn last year.

This year, it is forecast to bring in £2.6bn. And the average for the next five years: £0.7bn, or £700m, falling as low as £600m in 2016-17.

The chart above comes from the Office for Budget Responsibility. It shows that, since 2012, the forecasts for oil taxation revenue have undershot the forecasters' expectations. The dotted line is the one that covers the most recent forecast, and shows how far the tax take is thought to be falling.

Even if the oil price rises, there are other elements to explain why this will probably remain low. Tax is, after all, a share of profits, and profits are down to a combination of revenue, costs and investment allowances - the latter two having been very high recently.

At a time when the Scottish government is making the case for full fiscal autonomy, including a share of offshore oil and gas tax (estimated most recently at 84% of the UK total), that drills a significant hole in its argument.

Ring-fenced

The message George Osborne was least clear about in his 2015 Budget was the squeeze yet to come. He's re-profiled the next five years, which - happily for him - removes the Labour accusation that he was intent on taking the public sector back to the 1930s.

We are now facing a £30bn smaller budget. Some £5bn of that is supposed to come from cracking down on tax avoidance and evasion, and on those who advise on it.

Another £12bn is supposed to come out of the welfare budget. As pensioners are protected, that loads more of the pain onto working age benefits. The remaining £13bn is in departmental spending cuts.

We know the main parties are committed to various ring-fences around the NHS and schools, and perhaps around overseas aid. We'll soon know better what the Institute of Fiscal Studies calculates is the consequence for the other spending departments. But before this budget, it estimated a 14% squeeze on public spending translated to a 27% squeeze on unprotected departments.

This continues to favour - relatively speaking - the block grant that comes to Scotland, because the biggest items on which changes to it are calculated are health and education. But there's still a squeeze coming for those preparing manifestos for Holyrood election, for which the campaign will be in full swing a year from now.

Scottish income tax

Why, though, is the Treasury planning to lop £5.4bn off the block grant next year? That's right: £5.4bn less coming to Holyrood.

This is the figure in one of the more obscure bits of paperwork that accompanied this year's Budget. This is the calculation of how much Scotland can expect to raise in 2015-16, when it takes over control of roughly half of income tax.

That leaves Holyrood to raise £4.8bn from income tax, if it wants to retain Westminster's spending plans, and £510m from Land and Buildings Transaction Tax, the replacement in Scotland for Stamp Duty. That sum should focus some minds at Holyrood.

Raising a dram

If all this calls for a dram of whisky to steady your nerves, it should cost 2p less in a pub, or 16p off the average (£12.90) bottle of Scotch.

Whisky distillers were the other industry that got precisely what they asked George Osborne for. Perhaps they should have asked for more, but as this was only the fourth cut in whisky duty in the past century, then low expectations may have led to a low target.

Will it make much difference to the industry? Well, the Scotch Whisky Association (SWA) reckons it could turn around the decline in UK sales, this being its third biggest national market. It could send a signal to governments in export markets, that the UK Treasury no longer provides an excuse for ever rising tax elsewhere.

The SWA cited "independent research by Ernst & Young concluding that a 2% duty cut would deliver a £1.1bn boost to the public finances through increased investment, higher tax revenues, and from jobs created through the supply chain and hospitality sector".

Let's now see if that was right. But as only 7% of Scotch whisky production is taxed in Britain for British consumption, this is an industry with its focus on a horizon some way beyond the Treasury in London.

Update

The latest from the Institute of Fiscal Studies points to a big gap opening up between the scale of Scotland's notional deficit and that of the UK.

Because oil revenues are falling fast, it forecasts the deficit over the next financial year will be 8.6% of gross domestic product (or national output). The comparable UK estimate is 4%.

The gap between those two figures now looks like £7.6bn.

This was raised in first minister's questions by Labour's deputy leader Kezia Dugdale. The answer was that everyone got their forecasts wrong. Nicola Sturgeon pledged an update of Scottish government forecasts as soon as possible, and suggested that her critics should look at the shape of onshore public finances. They're rising by £15bn over the next five years.

How did she come by this figure? It's from Fiscal Affairs Scotland, where John McLaren and Jo Armstrong responded to the Budget with an analysis showing onshore tax receipts rising from £50bn in 2013-14 to £65.2bn in 2019-20.

Is this because of inherent strengths in the Scottish economy, suggesting it's pulling ahead?

Not really. Fiscal Affairs Scotland drew those numbers from an 8.2% share of the UK's onshore tax receipts, so they depend on the same assumptions about the strength of the UK economy as the strength of the Scottish one. The relative position being forecast remains the same.

- Published18 March 2015