Go compare: Scotland's place in the world

- Published

Ronald Reagan got into the White House with the question: "Are you better off than you were four years ago?". So 35 years later, are you better off than at the last election?

Part of the answer is the highly contested issue of real spending power. Tories can tell a positive story using real household net income (including benefit and tax changes as well as pay), while Labour prefers to tell a negative story about squeezed spending power, using real earnings.

But how are we doing on the international league table? On the day that international affairs intruded into the election campaign at leadership level, maybe we should look at how Scotland's getting on in the world.

The findings might even have a bearing on any further prospect of another independence referendum, because such numbers were heavily used to emphasise that Scotland's economy could be treated at least as a going concern, or a potentially very successful one.

Those number-crunchers at Fiscal Affairs Scotland (FAS) have been looking at the latest revisions to our GDP, or gross domestic product. These are big revisions, bringing Scotland into line with the UK, which last autumn came into line with the rest of Europe.

It draws a wider definition of output, including research and development and, as you'll recall, illegal drugs and prostitution. And it means Scotland's GDP is 3% bigger than we thought.

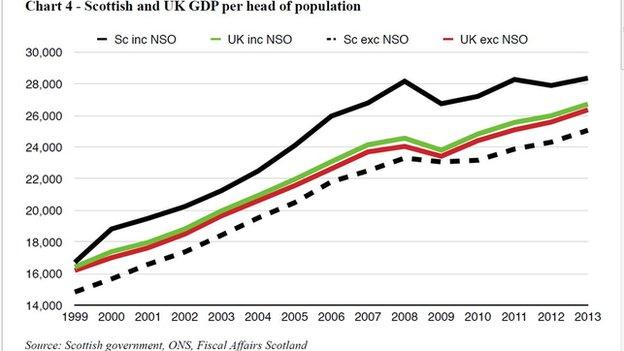

John McLaren and Jo Armstrong at FAS have bashed through the numbers and concluded that, measured by GDP per head in 2013, Scotland would be ahead of the UK as a whole, by more than £1,600 per head. Because of the inclusion of oil, that advantage has narrowed from 14% in 2008 to 6% in the most recent figures.

Foreign owners

But comparing Scotland with the rest of the UK only tells one part of a rather more complex picture for an open trading nation.

Using international comparisons, Scotland is reckoned to be at number 14 in the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development club of economically developed nations. That's down from number 7 in 2008. The high placing, and the volatility, are due to the inclusion of oil and gas from Scottish waters.

The output per head rose in 2013 to $40,600 per head. That's less than Luxembourg, which is in a league of its own, largely because people from neighbouring Germany, France and Belgium commute into the duchy, and their high-value financial sector work counts towards its output. For guidance, Norway is second-placed at $66,000, the US fourth at $53,000, Denmark 10th at $44,000 and the UK as a whole is 15th, on $38,000.

That helps give a sense of the size of Scotland's tax base, but it's less meaningful than it would be for most countries.

A distinctive factor is that large sectors in Scotland's economy - oil and gas, whisky, salmon, electronics - are largely owned outside the country. Their profits count towards GDP, but don't stay in the country. This is similar to Ireland, with a lot of inward investment.

Another factor is that being an oil and gas producer means commodity inflation can be helpful to the economy, just as the recent oil price drop is a big problem for that sector. This is similar to Norway. Where Scotland is particularly unusual is in having both the Irish and the Norwegian considerations in measuring the success of the economy.

Profit flows

That's why FAS has looked at the Net National Income, including the outflow of profits to owners and shareholders outside Scotland as well as the inflow of profits to investors in Scotland, while considering how inflation rates affect economies differently.

Drawing on experimental work by Scottish government statisticians, but warning that they look bullish, they assume that Scotland loses around 5% of its GDP after profits are accounted for. That's much less of a hit than the 15% to 20% lost from Ireland's GDP.

That way of counting puts Scotland a bit lower down the OECD league table, around 15th to 17th place, and behind the UK at number 14. It knocks Luxembourg of its pedestal, to be replaced by Norway and Switzerland in first and second place.

I'd argue that the lesson to draw from this is not that Scotland is better or worse than the UK, but that its economic performance is very close. (And please don't confuse this with its fiscal position, the subject of much election debate, and which is a very different story.)

Negative growth?

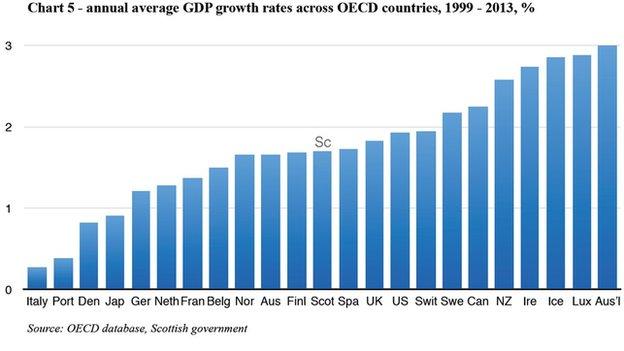

That much is a snapshot for 2013. How about the growth rates over time? This, too, has been deployed in the case for independence.

This FAS analysis shows Scotland's onshore economy (excluding oil and gas, as no data including it is available) Scotland's average growth over 15 years has been 1.7%. That puts it around the mid-point of developed economies. Including oil and gas could well put Scotland into negative territory, as those are the same years that offshore production has been declining.

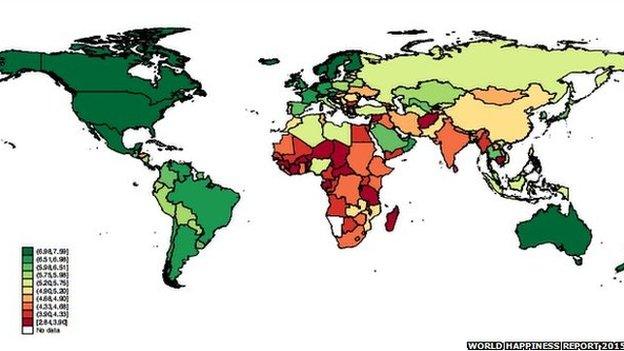

There is, of course, another way of measuring how well we're doing, and that's happiness. Pioneered by the Himalayan mountain kingdom of Bhutan, the latest global measure of that elusive commodity, external has just been published.

There are various of measuring this, starting with a Gallup poll, which asks - on a scale of one to 10 - if you are living the worst possible to the best possible life. Between the averages for the 10 happiest countries and the 10 unhappiest, there's a four-point difference.

But to get at this in more detail, the World Happiness Report 2015 turns to other measures. One is GDP, but the formula for happiness balances it with non-economic measures - healthy life expectancy, freedom to make life choices, social support, generosity and perceptions of corruption. For statistical reasons, it's all benchmarked against a fictional, worst-case scenario country called Dystopia.

There are different patterns of happiness in different countries, but on average, women are slightly happier than men, and the young more so than the middle-aged. Happiness levels tend to level out from middle to older age.

Those at the top include Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, Denmark, Sweden and Canada.

So there's something going for democracies in northern latitudes with harsh or dark winters and light summers. They also tend to have lower inequality measures and strong social support structures, indicating a lot of trust between people and in institutions. The reverse side is a general mistrust, communities which isolate themselves and lawlessness.

The UK comes in at number 21, behind Belgium and the UAE, and just ahead of Oman and Venezuela. There's no Scottish measure in the 2015 World Happiness Report. And if you go to the bottom of the table of 158 countries, you'll find Togo, Benin and - miserably, unsurprisingly - Syria.

What difference can all this make? Well, the social and neuro-science of happiness is taking up more and more government thinking time these days, with a realisation that worship at the altar of the GDP deity is a narrow way to define a country's life.

If happiness is pursued, instead of economic growth, it means that the measure of, say, a social policy, gets a very different type of cost-benefit analysis.

And to improve happiness, this report recommends better mental healthcare, early childhood development programmes and healthy environments as forums to develop trust.

And that can be as simple as safe, welcoming parkland. Time for a weekend walk.