Jings! Crivvens!

- Published

The SNP secured 56 of the 59 seats available in Scotland

What's changed?

A lot.

Five years ago, the political map of Scotland remained unchanged from the 2005 election, even though there was a new complexion of government at Westminster, and even though the SNP was in power at Holyrood.

That was probably a key contributor to Labour and Lib Dem complacency about the changes taking place electorally.

It appeared that Scots had learned to vote one way for Holyrood and other ways for Westminster, all but six seats sending representatives to Westminster who would fit in with the Westminster system.

What they didn't appreciate was that such new-found voting promiscuity unsettled the foundations of Scottish politics, and set the conditions for the colossal landslide of 2015.

So what's changed is that the SNP has not only won 56 out of 59 seats, but it has them with thumping big majorities (not what you find at Holyrood). Tactical voting was a significant factor in Labour retaining Edinburgh South, and Alex Salmond didn't enjoy the same monstrous swing that his colleagues saw.

And there are now more pandas in Scotland than either Tory, Labour or Lib Dem MSPs. There is effectively no British party system any more.

Why did the SNP do so well?

Before we get to see the detailed exit polling from academic research, here are some factors that may have weighed on the Scottish votes.

The SNP ran another highly effective campaign, focused on a simple message, backed by a highly motivated, disciplined and well co-ordinated campaign machine, with more than 100,000 members wanting to get involved.

The leadership debates gave Nicola Sturgeon a platform to show off her debating skills

Nicola Sturgeon was on the back foot over Scotland's public finances and the difficult message of "switch from Labour to SNP, and thus ensure you get a Labour government". But none of that mattered much, when set against the relentlessly upbeat image projected through the media.

The leadership debates gave the SNP leader a platform to show off her well-honed debating skills and put her on the same level with the Westminster leaders.

She took full advantage of that opportunity. Anecdotal evidence suggests that even voters who don't support the SNP or independence could share some Scottish pride in her performance.

But the risk for the SNP (and one they face next year at the Holyrood vote) is that they take all the credit without realising how helpful their opponents were.

Labour people know their party has been hollowed out. The membership base is rotten. Councillors lost ground through the new voting system, the organisational base was eroded, and there was a lack of support between different levels of representation.

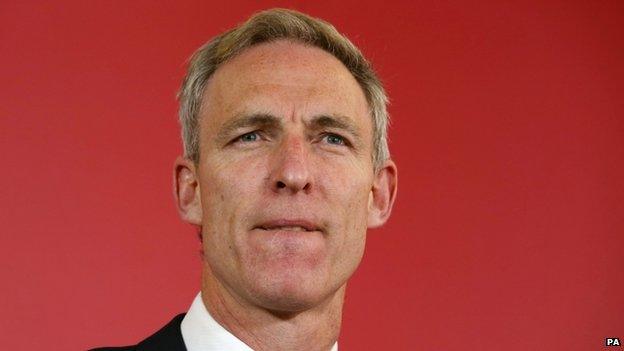

The message was unclear. Jim Murphy became leader in December, carrying political baggage as a Blairite which was difficult to shake off, however frenzied his campaigning. It wasn't clear why his concern to win the right to buy alcohol at football grounds fitted in with the strategy for 7 May.

Labour's strategy wasn't clear, between the tactics of shifting from populism to a core vote appeal, to an attack on economic grounds, none of which found much traction.

Jim Murphy became Scottish Labour leader in December, carrying political baggage as a Blairite

The manifesto and message was constrained by the need to look fiscally credible at Westminster, while the SNP could promise 'an end to austerity' in the knowledge it wouldn't have to implement it. The credibility doubts about Ed Miliband wouldn't have helped either.

Lib Dems had obvious problems, which were common to Scotland, England and Wales, about defending their role in government over the past five years. It seems a tad cruel that their coalition partners were the main ones to benefit from their difficulties in reaching out to their previous voters. It's perhaps even more so that they were punished for breaking a pledge on student tuition fees that didn't even affect Scottish voters.

This is a bad advertisement for being a junior coalition partner, as Lib Dems had also found at Holyrood. They came out of the first Scottish coalition quite well, the second one quite badly, and then plummeted to a terrible result in 2011. Parties will take note in future, including those at the Scottish Parliament.

What role did Scotland play in the result across the rest of Britain?

The evidence is building up that David Cameron shifted the dial in the closing stages of the campaign with his warnings to English voters about the risk of Labour being "propped up" by the SNP.

He was denounced for it, as it appeared to undermine the Tories' standing in Scotland by arguing that Scottish votes were not legitimate if they elected a non-unionist party.

But it was clear from the BBC Question Time that Labour felt the need to hit back hard, with Ed Miliband distancing itself further from the SNP, to the extent that he would prefer to have David Cameron in Downing Street than to work with Nicola Sturgeon's party.

Comments since the results came in make it clear that the Conservative targeted message hit home where it needed to bring UKIP voters back into the Conservative fold. Nigel Farage has said as much.

What does the result "mean" and what happens now?

The "meaning" is a big and difficult question, and there will be a race to see who can best define it.

One clear meaning is that Scottish voters want change. But as the SNP campaign was explicitly not about independence or about a mandate for another referendum, it has to be careful how it interprets its mandate.

With more than 100,000 members, many will be impatient for the momentum of this Westminster result to be maintained towards a second referendum, and that is a pressure Nicola Sturgeon will have to manage. That looks like a nice problem to have.

If it had been supporting a Labour minority government "to keep it honest", it could make demands. But with a majority Conservative government, it's less clear what demands to make.

Full fiscal autonomy, or responsibility, at Holyrood - going far further than current plans, to give MSPs the full range of taxes - is popular with the party, but there's a risk for Nicola Sturgeon that she gets precisely what she asks for, and faster than she wants it.

That's because the additional £7.6bn deficit, outlined by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, is on track to get bigger, while the Tories plan to cut the UK deficit sharply and reach surplus within three years.

David Cameron has a difficult hand to play in his next meeting with Nicola Sturgeon, but he must be tempted to give the first minister all the tax powers, and leave her to deal with some potentially painful consequences.

However, by doing that, he could be accused of undermining the union, and hastening a move towards an independence referendum.

One complication will be his pledge to reserve English laws for English MPs, while he's created a big challenge for himself in another area of the constitution, first in getting a deal out of other EU heads of government on European reform, and then on taking it through a referendum.

David Cameron has a difficult hand to play in his next meeting with Nicola Sturgeon

The negotiation between Cameron and Sturgeon will be between a party that dominates in England and the party that utterly dominates in Scotland.

Cameron has a mandate too, and on two big issues for the SNP - the shape of deficit-reduction and the future of nuclear weapons - it doesn't look like there's much room for compromise. This will be unlike any cross-party negotiating we've seen before, with more of a literally inter-national dimension to it.

Is there any silver lining for the losers?

The SNP's gains and losses for Labour and the Liberal Democrats are the astonishing stories of the 2015 election.

For both Labour and the Lib Dems, there is now a pool of more experienced candidates, out of a job at Westminster, with whom they could fight next year's Holyrood election. Their talent pools needed a bit of deepening anyway.

It's also worth noting that Conservatives held one seat in the face of the SNP deluge, and nearly won a second in the Borders. The share of the vote was down less than 2%, although that's from a low base.

After many elections of struggling to be heard, perhaps Ruth Davidson has successfully used the referendum campaign to break through to voters for whom the long memory of Thatcher holds less potency.

Her closing campaign message was clearly pointing to the Conservatives as the party of the union. She must wish that David Cameron had avoided doing that message such harm.