Imports to keep the lights on

- Published

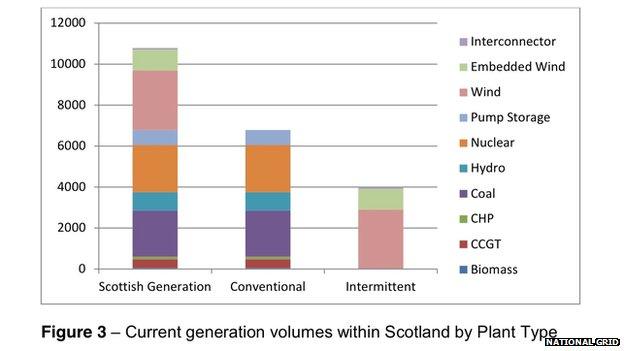

It has been warned that the closure of Longannet power station could make Scotland dependent on power from south of the border

The challenge of keeping the lights on has returned to Holyrood, with MSPs looking into the security of the nation's energy supply.

"The nation" is a flexible concept here, as this is a Scottish viewpoint, when everyone agrees that the energy market should remain British, if not expanding into a European single market, with the help of more sub-sea inter-connectors.

Appearing before the enterprise and energy committee are the big energy utilities, and their regulator. Scottish Power and SSE (Scottish Hydro, to most of us) are among those under pressure over consumer bills.

They had made it clear that prices were stuck while they waited to see if Ed Miliband and Labour would follow through on freezing prices. That interventionist policy also had the unintended consequence of raising investment risk.

With Miliband defeated and a less interventionist government in power at Westminster, it follows that prices should now fall, and investment plans can be taken out the chiller.

However, SSE and Scottish Power have another major role to play in supplying energy. Along with National Grid, they have responsibility for keeping the energy distribution system functional. On that score, the pressure is being exerted in the other direction - telling politicians they need to get their acts together.

Longannet no more

MSPs have been told there remains a significant risk that Scotland will be left without sufficient electric power, particularly if thermal plants, including Longannet, are closed down before there is sufficient capacity in place to import power from the south.

That means that there will be several years when high demand for power will be met with low supply of renewable energy (a cold, windless period in winter, for instance) and there won't be enough back-up in Scotland.

The capacity to export renewable energy is being expanded, with new power lines, re-cabling and a sub-sea inter-connector from Ayrshire to Merseyside, at a cost of more than £1bn. The key elements should be operational by 2017. But it looks all the more important that this is available for importing power.

National Grid calculates that only around half of Scotland's peak demand (2.6GW, out of 5.4GW) can be met by inter-connectors with England until the west coast sub-sea connector is complete.

If the north of Scotland lacks wind power, it can pull on 65% of what it needs at peak demand, at least until the new Beauly-Denny inter-connector is in place.

National Grid has modelled around 1,000 scenarios for what could happen if the wind drops, without Longannet or the Cockenzie coal-burning power station and at least one other nuclear generator is out of action. With the results in mind, they're paying SSE to provide back-up capacity at its gas-burning plant in Peterhead.

Cooking without gas

Scottish Power, which has responsibility for the grid in central and south Scotland, warns that the closure of Longannet power station, likely be March next year, will make resolution of an energy crisis in Scotland largely dependent on importing power from south of the border.

It says current emergency plans depend on Longannet, so they need to be re-drawn ahead of its closure. And medium-term, there needs to be new consideration of how to provide back-up capacity in Scotland.

One option is to put gas-burning turbines into the former coal-burning plant at Cockenzie in East Lothian, but such an investment makes no financial sense at current profitability on gas-burning.

SSE, with responsibility for the grid in the north of Scotland, has other points to make to MSPs. In addition to payments made to generators to ensure spare capacity in case of shortfalls elsewhere, it wants to see more certainty and stability for pricing, lasting further into the future.

It also returns to the question of the cost to generators of contributing to the National Grid from the North of Scotland.

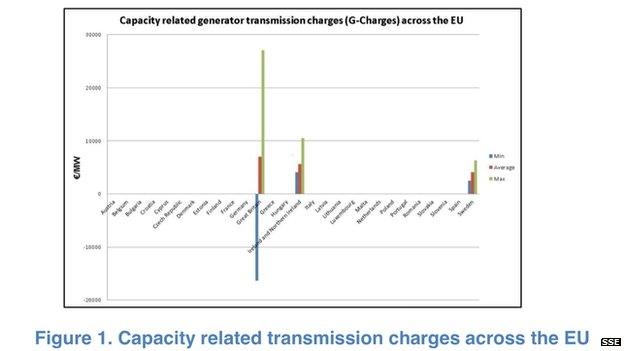

This involves a high charge per unit of electricity, while southern England gets a sizeable subsidy. It's a pricing system intended to create incentives for generators to build close to population centres. And although the gap between northern cost and southern subsidy is being narrowed, it remains in place.

Uphill struggle

This plays to that pervasive narrative of Scotland being disadvantaged by policy set in London. And SSE has a telling graphic illustration of how wide of the European norm this is:

That shows Ireland is the only other part of Europe to have price incentives to help generators choose where they locate their power stations. But Britain's are far stronger price incentives, and far removed from the case for generating renewable power where it is most plentiful.

They will be further complicated if the newly-elected Conservative government puts the brakes on onshore wind developments, responding to local community pressure.

Once again, the industry sees this as short-term thinking, when it says it needs stability if it is to re-orient power supply around low-carbon technology. SSE has a wonderfully diplomatic way of telling the government it's wrong and should think again:

One other argument being made by green groups as well as the power companies, is that back-up storage to keep the lights on when the wind drops could be much better supported.

Pump storage is a specialised use of hydro power. It takes wind power when demand is low (at night) to pump water from a low to a high reservoir. That is then available for switching on at short notice, usually for short periods.

SSE has a plan on the drawing board for a big new project that has the potential to provide 600 megawatts (quarter of Longannet's maximum output, or around 300 large wind turbines) for up to 50 hours. However, it sees "no route to market". In other words, the investment incentives are not there.

The evidence reflects a lot of progress made on closing down the risk that the lights could go out, with next winter being the riskiest of all, and the problem of tight capacity margins persisting at least until 2018.

But the evidence also requires a reality check for those saying Scotland can be self-sufficient in renewable energy and an exporter, and that it doesn't need nuclear power.

It can be a net exporter, but that brings with it more dependence on imports when renewable energy doesn't deliver. And those imports are bound to include nuclear power - if not from England, then from further afield. Britain's capacity for transferring power to and from the continent is being increased from 4GW to nearly 11.

That's the build-up of the Europe-wide electricity market, in which Scotland's grid access charges become harder to explain, and in which solar power from the south will compete directly with wind and marine power from the north-west.