The road to Paris and beyond oil

- Published

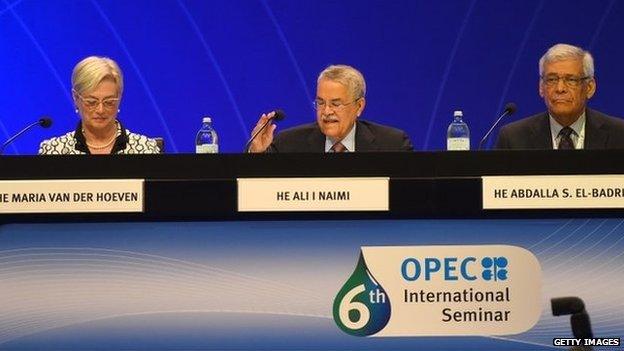

The world's big oil exporters are due to attend the Opec meeting on Friday

The world's big oil exporters meet every six months in Vienna. Last November, as prices slid, Venezuela pushed for a tightening of supply to push prices up again. Its public finances badly needed that.

The Saudi oil minister, who calls the shots in the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec), disagreed. He wanted to maintain market share, and intended to keep pumping.

So began a slide in the price of a barrel of Brent crude, as low as $45 in January and more recently stabilising around $65. It sent Venezuela into a crisis, and put a lot of pressure on the oil industry to cut costs and investment. The mature and relatively expensive UK North Sea has been seen as a prime target for the accountants to cut back.

Opec's members meet again in Vienna today. There's not much expectation of a change of course, or of price. The cartel's production levels have remained higher than they were, and may get higher still as Iran aims to remove sanctions and returns to exporting. The meeting is expected to be short.

Political failure

But there's something else stirring in the industry and in large corporations elsewhere. Business is taking a lead on the case for cutting carbon emissions.

This is partly because politicians are failing to do so. Britain's new government can be expected to move away from green measures, such as support for onshore wind power.

While Russia is dependent on exporting its oil and gas, China's is one government taking environmental degradation more seriously, and India is investing in a lot of solar energy.

But as more candidates join the race for the White House this month, this is not a particularly auspicious time to expect America to take a lead which sacrifices voters' cheap-fuel, energy-rich lifestyles.

Flat-pack solar panels

Another reason for this heightened corporate interest may be "greenwash" - a desire to be seen by customers to be doing something about the environment.

Ikea is trying to impress customers no doubt, but on a scale that suggests it's not just for show.

Ikea says it wants to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from all aspects of its operations

As a family-controlled firm, the Swedish furniture retailer has the luxury of being able to announce this week that it's spending a billion euros on cleaner energy and support for those most affected by climate change. It already owns more than 300 offshore turbines and has installed 700,000 solar panels on its buildings.

Corporates which have to be more sensitive to financial markets are warily eyeing the campaign to pull investments out of fossil fuel, which has become a movement in university campuses, extending to big fund holders such as French insurer Axa.

The "keep it in the ground" campaign is championed by The Guardian. Lenders such as the Royal Bank of Scotland have come under pressure to defend their carbon footprint, particularly in funding tar sand extraction in Canada.

Carbon tax

For the energy industry itself, there's another explanation for this interest in cutting emissions. It may be because a shift from fossil fuels to renewables is beginning to make more commercial sense.

That's particularly for those who factor in the longer-term impact on their businesses of significant climate change. But long before that, the plummeting cost per unit of solar panels could be challenging the economics of conventional power stations.

This year looks like an opportunity to drive that message to Paris, where another of those vast and often frustrating climate change summits (think Kyoto, Buenos Aires, Copenhagen etc) will seek once more to find common ground on which binding action can be taken.

The leaders of western Europe's big six oil and gas companies - BP, Royal Dutch Shell, Statoil, Total, Eni and BG - banded together this week to press the case for a level playing field, and one which involves a higher price on the very stuff they produce.

They call it "carbon pricing", but it looks suspiciously like a tax on raw energy as it enters the market - the cost cascading through the supply chain to the customer. The idea is that it ought to cost customers least where there is least carbon output. So the market signal will encourage producers to seek out low-carbon options and technologies.

Old king coal

A further explanation for their concern is that gas demand has been undercut by a rival energy source, coal. In the Atlantic market for coal, it became much cheaper when undercut by North American fracked gas. Power generators and industry re-tooled for a gas future.

But according to a report this week from the International Energy Agency, growth in gas demand for much of the world now appears to be slowing due to the growth of coal burning, at a low coal price, and a big expansion of renewable energy capacity.

New and expensive investments in liquid natural gas terminals and carriers are being shelved, though for Europe at least, that source of gas will rise significantly for the rest of this decade.

So the battle is on to squeeze out coal. "For natural gas, the case is simple," wrote the European energy chief executives. "When burned to make electricity, it typically generates around half the carbon emissions of coal.

"Gas can provide the electricity base load that is required and can be a flexible partner to renewable as efforts continue to improve the storage of electricity produced by intermittent solar or wind."

However, they add, they're not looking for special favours for gas production: they want a level playing field, so that costs on European production are matched by other countries, and no one country gets a trading advantage.

"Pricing carbon obviously adds a cost to our production and our products, but a stable, long-term, global carbon pricing framework would provide our businesses and their many stakeholders with a clear roadmap for future investments."

It probably comes as no surprise that the boss of Chevron sees such a proposal as unworkable, because his customers simply won't accept it. "They want low energy prices, not high energy prices," he is quoted as saying - with blunt simplicity.

Blast off

The drumbeat towards the Paris summit is getting louder, with green lobby groups gearing up, and an interesting proposal also out this week from the Global Apollo Programme.

This British-based gathering of scientists, policy-makers and business-people wants to portray the challenge of climate change as akin to putting a man on the moon - a positive vision, and achievable ambition. A similar financial commitment to the US space programme between 1961 and 1969 could achieve what currently seems technologically impossible.

The difference, as they don't point out, is that people's transport and heating bills didn't go up to pay for Neil Armstrong's giant leap for mankind - or at least, not in any way that consumers could see.

- Published4 June 2015

- Published3 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015

- Published2 June 2015