Deficits: good or bad?

- Published

For those of you who fondly remember last year, we're back in familiar territory, with talk of the deficits Holyrood might face if it had full control of Scotland's taxation.

Short of independence, the Scottish government and 56 SNP MSPs would like full fiscal autonomy - that is, all tax-raising powers, while paying a fee to Westminster for shared roles, such as defence and foreign affairs. Or even funding the UK's £1.5tn debt interest payments.

That's been built up by years of over-spending. Conservative politicians from Margaret Thatcher to George Osborne have portrayed the public finances in terms of household finances. They like to pay out no more than they take in, and to "fix the roof while the sun's shining".

The Chancellor is to push a law through Parliament which would require balanced budgets, unless there is good reason not to have one.

Countering the slack

The tricky bit is deciding when that is, as my colleague Robert Peston explains.

Many economists believe a government ought to run deficits to counter the slack demand in an economic downturn. To cut spending when the economy's weak, as the government has been doing, is to undermine or slow up its recovery.

There's also a case for running a deficit to invest in infrastructure which can help the economy to grow. If better transport, for instance, helps boost productivity, then it's money well spent.

And amid all the other arguments about the economy, there's agreement that low growth in productivity is the big issue Britain needs to sort out. We can expect a productivity plan from the Chancellor next month, perhaps when he has his post-election budget announcement, on 8 July.

The easier bit is spotting that this is a trap for Mr Osborne's Labour opponents, who were skewered during the election campaign over their previous spending habits. They currently lack a leader who can decide how to respond to the Bill - one of the key strategic decisions Ed Miliband's successor will face.

So what about the SNP? It's clear that it approves of deficit financing. That's what its "anti-austerity" rhetoric is about. The next bit of the argument is that Holyrood should have the power to choose how big its deficit is. And that looks awkward.

The party's manifesto included support for full fiscal autonomy. That goes naturally with wanting independence.

The catch is that the Scottish government's own figures show that Scotland would currently be running a very large deficit - far larger, proportionately, than the UK as a whole.

That does not show, as some suggest, that Scotland has been left straggling by Westminster rule. It reflects Scotland's level of spending per head, which is higher than the UK, while it has onshore (non-oil) tax revenue thought to be roughly the same per head as the UK.

In other words, it's the higher public spending that appears to create this problem, much of which will soon be down to Holyrood's choices. It's no reflection on the relative position of the economy.

Over a barrel

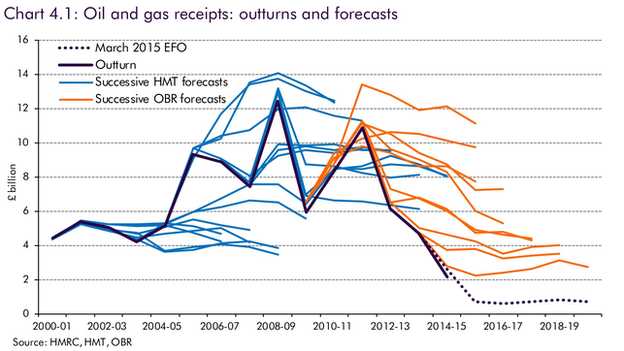

The spending-revenue balance was in a relatively good position while the oil price was above $100 per barrel. Offshore tax contributed £11bn in 2011-12.

But the price of Brent Crude has fallen. As the North Sea matures and costs have risen, production is sharply down, as are the profits on which tax is levied.

Until the end of this decade, Scotland's share of oil revenues is forecast by the Office for Budget Responsibility to be around £700m per year - just above 1% of total government spend in Scotland.

Today, the OBR has gone further, and published its long-term forecasts for 2020-21 to 2040-41. They have plummeted since last year's forecast. It is estimated that the total tax take from offshore oil and gas over those two decades will be £2.1bn. That's down by £34.5bn from the estimate published last year, and less than the tax revenue from last year alone.

Part of that is because of the cut in tax rates, on which there is cross-party agreement. The direct effect of the fall in oil prices explains £15bn of the reduction since last year's forecast. The indirect effect is that fields will become financially non-viable at those lower prices, so production will fall, meaning £13bn less over two decades.

If you compare the latest estimates for those two decades with the long-term forecast published by the OBR in 2011, that £2.1bn figure is down by £129bn.

The central estimates point to the importance of offshore revenues falling to 0.004% of national output. If the revenues were to accrue to Holyrood, you can multiply the share of national output by roughly 10, and get to offshore revenues accounting for four hundredths of 1% of Gross Domestic Product.

That calculation may be wrong-headed. The OBR has pointed out that all of its previous predictions about oil and gas revenue have been higher than the out-turns, and that estimates remain "highly uncertain".

But The Scottish government's plans to publish its own updated figures "as soon as possible" (Nicola Sturgeon in March) seem to be stuck in a pipeline somewhere.

World-class growth spurt

So here's the problem for the SNP group at Westminster. Their manifesto and their political creed points to Full Fiscal Autonomy.

But it doesn't look a very attractive prospect unless Scotland can close the deficit by unleashing a world-class growth spurt, and the taxes to go with it.

Today, we've learned that Westminster leader Angus Robertson is pushing for the Scotland Bill to give Holyrood the power to take on taxation at a time of its choosing, and no doubt on conditions of its choosing as well.

If there was any fear that English Conservatives would happily hand over this headache to Holyrood (and some must be tempted) that conditionality makes it a lot less likely.

Fade to black

Mr Robertson has also sought to portray the Scottish deficit as being no bigger a problem than the UK's deficit down the years. He points out it has been in the red for 43 out of 50 years.

He points out also that the UK's deficits in the five years to 2013-14 added up to £600bn.

This appears to dwarf the £7.6bn deficit figure for Scotland this year, calculated by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, with a similar number coming from other sources.

So let's remind ourselves what that means. The IFS calculated that figure as the additional Scottish deficit, on top of Scotland's share of the UK deficit for this year.

And while Mr Osborne (controversially) wants to cut the UK deficit to zero within three years (having failed to do so by now, under his previous plan), that would leave him in the black by the end of this decade, while Scotland's deficit would be nearing £10bn.

What then? Well, remember another part of last year's independence debate - the bit about currency?

It was clear that if Scotland was to share a currency with the rest of the UK, then it would have to accept fiscal limits set by its southern partner. And if Westminster has a law on balanced budgets, it's not likely to tolerate that kind of Scottish deficit - independent or not.

Apples and rotten pears

Leaving that aside, would that scale of deficit affordable? Possibly, but only if you've got the economy growing much faster, with much better productivity. On current output levels, it would be roughly double the scale of deficit that the eurozone countries are supposed to stick to.

Of course, several European countries have driven a coach and horses through that threshold of 3% of national output, as a result of the recent financial crash and downturn. The UK's coach and horses was bigger than others.

The eurozone rules, to ensure stability, also say that a nation's total debt should be no more than 60% of Gross Domestic Product. The UK's debt is heading north of 80%.

So while Angus Robertson is right to say that Scotland's challenge is dwarfed by the UK's recent overspending, that misses the point that UK overspending was vastly bloated for several years, and unsustainable.

You might say he's comparing expensive Scottish apples with some really rotten Westminster pears.