Who wins from workplace flexibility?

- Published

CalMac workers are due to hold a second strike next week

If you're reading this while waiting for a train this or coming Sundays, you may want extra battery power, as the wait may be longer due to services being harshly cut. There aren't enough drivers available, says Abellio, the new operator of ScotRail.

But don't worry, because another dispute will be along in a moment. CalMac crew are heading for their second stoppage, next Friday, to get leverage over the current tendering process for the west coast ferry contract. They fear for their job security if private sector Serco wins the bid over publicly-owned Cal-Mac.

The other place you may find yourself waiting is in the National Health Service. There is a significant shortfall of consultants to fill roles. The children's ward at St John's Hospital, Livingston, for instance, doesn't have sufficient doctors to fill its rota, so it's no longer able to take patients overnight.

The problems with the NHS isn't just about money, it seems. There's lots of it available, if provision of one locum psychiatrist in the Western Isles can cost £19,000 for only a week. That was in 2013, and since then, staff shortages have made agency staffing is all the more important.

Good or bad job?

Four news stories this week - and together they reflect on the changing shape of the jobs market.

MSPs recently put out a call for evidence and views on the quality of jobs in that changing market, ahead of a committee inquiry which will ask whether 'good' or 'bad' jobs are being created.

They could start with these recent examples. So here are some of the lessons you can take from these news stories.

For one, labour is shifting from a bosses' to a workers' market. That is, when the negotiating leverage of workers and their unions was low, through the downturn, they often had to accept real terms pay cuts, erosion of conditions and the reduced pensions that were imposed.

But with parts of the labour market tightening up, some workers feel better able to use their bargaining muscle.

Real terms pay is on the rise, though modestly, and it's got a lot of catching up to do.

Bargaining power

As you would expect, the market dictates that those whose skills are most scarce are the ones with most bargaining power. For quite a few years, those have been the top bosses - though some might argue their pay is more scandal than it is bargain.

A recent report by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) showed that recruiters reckon there's been a shift away from the hirers' market. Britain-wide, more than four-fifths say competition for talent has increased in the past two years, and more than three-quarters responded to the CIPD survey saying they have had recruitment difficulties in the past year.

Those in scarcest supply include people with specialist and technical skills, such as those in IT, followed by those sought for vacancies in top management. Their problems are exacerbated by changing requirements of workers, as the economy shifts, recovers and adjusts to further technological change and working practices.

In the case of the railway workers and ferry crew, a further dimension is the willingness to withhold their labour to protect employment conditions rather than promote their pay demands.

Whipping up a Hebridean gale

Both disputes are linked to the process of contracting out or franchising. Dutch-owned Abellio won the ScotRail franchise with a promise of better services. They have to take on staff under existing pay and conditions, but the key differentiator in the financial thinking behind these bids is what management think they can squeeze out of new recruits and changes to working conditions - overtime pay for Sunday shifts, for instance.

Rupert Soames, chief executive of Serco, an outsourcing giant, was on BBC Radio 4 recently, conceding as much. The private sector can seek out the flexibility that is hard to negotiate with public sector unions.

That's why CalMac crew want a promise soon that the guarantees of no redundancies will be written into their contracts, so that they have to be transferred across to Serco if it wins the right to run those ferries.

With Daily Record, Labour and union campaigning, it's whipping up quite a Hebridean gale. You wouldn't want to be the Scottish government minister who is obliged to announce that Serco has won, and publicly-owned CalMac is being wound up.

Backward-bending

Meanwhile, train drivers aren't refusing to fulfil their contractual obligations. They're choosing not to take overtime. They're entitled to do so.

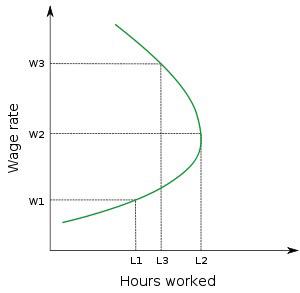

It has to do with something economists call 'the backward bending supply curve of labour.'

As with much of economics, this gymnastic-sounding graphic concept is much simpler than it sounds. On the y-axis is pay: on the x-axis hours worked.

At low levels of pay, people have to work long hours to make ends meet. Pay them more, give them more security, and they want more time to themselves.

Pay them lots, and they offer fewer hours because they want more leisure time, and the opportunity to spend all that moolah. That's where the curve bends back.

And that's where train drivers have something in common with doctors. To get the best out of workers, employers have required more flexibility from staff.

In many cases, they have chosen to depend on contractors, freelancers or self-employed people. They're easy to ditch when budgets are squeezed.

The CIPD survey found mixed evidence about how much that's spreading. Roughly one-third of respondents said they're using contractors more in the past year, but a fifth are using them less.

One third are having to offer permanent jobs to get the skills they need, rather than temporary posts, but nearly as many say they don't have to.

A big problem with depending on freelance workers or overtime is that you can't be sure the staff are available when vital services need them. And in a sellers' market for working hours, the trains and the health service find themselves in trouble.

Workforce planning

The problem is particularly acute with the health service. There's a lot of talk about 'workforce planning', but it appears sometimes to be more about 'workforce hoping-for-the-best'.

The taxpayer pays vast amounts to train doctors (including free tuition for Scots in Scotland), and rather less to train other health professionals, including nurses. The co-ordination and the numbers are handled jointly between the four parts of the UK.

In a global market for their skills, these health professionals can go elsewhere, and some can mint money by doing so. So can the doctors from Africa and Asia who are called on to plug many of the many gaps in the NHS. Migration of medics, in and out of Britain, is expected to increase further.

Doctors also tend to be towards the top of that backward-bending supply curve of labour. Because they command a lot of money and have skills that give them other options, they can choose to reduce the numbers of hours they work for the NHS, unless the job is made more attractive for them.

As the recent Greenaway review of medical training found, that includes better managed hours and flexible working. With most entrants to medical school being female, the attrition rate to family caring roles is high - and very difficult to plan for, when it takes so many years to train up a consultant. There is also survey evidence showing that male doctors, too, want a better work-life balance than the profession has known in the past.

Uber cabbies

One other dispute worth noting for signifying disruption to the labour market is in France. Taxi drivers are vigorously protesting against Uber, the taxi-booking mobile app which is undercutting conventional cabbies in cities around the world.

Technology has given us rapid growth in this 'on-demand' and sharing economy - matching self-employed providers and otherwise-unused assets (your home rental on Airbnb, for instance) with digitally-savvy customers.

Uber, in case you didn't know, has applied for licences to operate in Edinburgh and Glasgow. If successful, prepare for some very grumpy Scottish cabbies too.

- Published2 July 2015