Over to you, Business

- Published

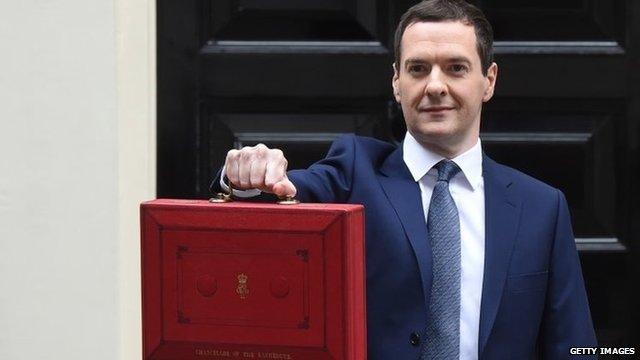

This was the first Conservative Budget since 1996

Nearly 20 years ago, Kenneth Clarke was delivering the last Conservative Budget in the House of Commons, at the same time his party was arguing that their Labour opponents would cost many jobs if they went ahead with their plans for a national minimum wage.

A few months later, Gordon Brown was Labour's Chancellor. That minimum wage was introduced, and set at a level where economists at the independent Low Pay Commission believed would give the maximum hourly rate to low earners which avoided damaging their employment prospects.

Twenty years on, and the current Tory Chancellor is not only committing to the minimum wage, but increasing it to a level where he concedes it is likely to cost 60,000 jobs. That's the estimate from the Office for Budget Responsibility, while it says that other Budget measures will create far more jobs than the new National Living Wage will cost.

We should be wary of the use of language here. The living wage is a concept designed to measure how much it takes for a household to have the necessities of life. Academic analysis has arrived at £7.85 for most of the UK, and £9.15 in London.

So the government has given up on a minimum wage which minimises job losses, preferring the rhetoric that "Britain needs a pay rise". But it is not acknowledging the case for a living wage in its original sense.

The new compulsory minimum wage is stuck somewhere between those two, rising for over-25s to £7.20 next April and £9 per hour by 2020.

Instead of leaving independent economic analysts to decide the compulsory level, there's a problem here. This has now firmly established itself as a political football. It can expect to get robustly kicked around in future election campaigns.

Sticks

The impact of that is the big unknown facing business, as it digests this radical Budget. We knew, beforehand, it was bound to cut the government deficit - for which most business representatives are signed up.

The welfare budget changes make some fundamental changes to the relationship between the government and the individual, in terms of personal responsibility.

What few saw was that there would also be a potentially historic shift in the relationship between government and business - also taking on more responsibility.

Protestors took part in a demonstration in London against the austerity measures

George Osborne explicitly said business had been using the tax credit system to subsidise jobs. He withdrew a lot of those family tax credits with a four-year freeze and a much lower threshold at which parents begin to see their credits taper off.

He increased the minimum wage. And as that averages 6% per year, with inflation targeted at 2%, it can be expected to have an impact on higher hourly wage rates for higher paid workers as they seek to protect their pay differentials. Well, you would, wouldn't you?

The Chancellor also hit bigger businesses with a training levy, to tackle the "free rider" problem of those who rely on other firms or on the government to fund their staff skills.

He took aim at banks, with an 8% profits surcharge to replace the levy. The renewable energy sector lost a sizeable tax exemption from the Climate Change Levy, about which it's very unhappy.

The motor industry is very concerned about the impact of changes to Vehicle Excise Duty. And the Chancellor expects to take £7.2bn out of business profits with a clampdown on tax avoidance schemes.

Carrots

Those are quite substantial sticks with which business felt beaten through the Budget statement. But there were significant carrots too.

For small firms, there is a rise in payroll tax break, and medium-scale enterprises can expect to benefit most from a steady £200,000 annual investment allowance - intended to tackle one of the productivity weaknesses in the British economy.

The main rate of corporation tax is coming down from 20% of profits, to 19% in 2017 and 18% in 2020. Compare that with the main rate only 33 years ago of 52%, and only eight years ago, it was still at 30%.

Would the SNP raise the minimum wage further?

That fall poses an interesting challenge to the SNP. Does it still want the powers at Holyrood to go lower still?

There are other challenges to it here. If it were successful in gaining power over the minimum/living wage, would it raise it further, at a cost in jobs?

And will the SNP choose to use the power over income tax variation, which it takes on from next April, to boost its budget in order to pay public sector staff more than the 1% cap they face from Whitehall?

Negotiations were under way this week between Scottish Finance Secretary John Swinney and Treasury ministers about the size of cut in the block grant to Holyrood which will accompany that new income tax power.

We're also told that a new system for funding roads will require a deal to be done between Whitehall and the devolved administrations.

It seems Vehicle Excise Duty is to be reformed, and then ring-fenced to pay for better roads infrastructure. How that gets devolved has yet to be discussed.

Pay and skills

And that points to the underlying theme of much of this Budget. It fits with Conservative thinking (though not always with its recent history) that responsibility is pushed outwards.

There was a strong message on significant powers going to English mayors and city regions, even where there has been a past reluctance to accept devolution.

George Osborne gave responsibility for part of his welfare budget to the BBC, providing free TV licences to those aged over 75.

If roads funding is separated from general taxation, that could become the means for some more radical reform, heading towards road charging, for instance. No politician can afford politically to introduce it, but congestion-based pay-per-mile makes a lot of economic sense on a crowded island.

There are more pensions reforms on the way, only up for discussion now, perhaps involving a Pensions ISA (Individual Savings Allowance), with the intention of moving individuals from saving a bit, to saving enough.

So while parties to the left tend to prefer responsibility being exercised collectively and socially, the Conservative strand running through this July Budget was about handing responsibility to individuals, with less of a welfare safety net but with lower tax as an incentive - and also to business, with further lowered tax, but more responsibility for the pay and skills of its workers.

- Published9 July 2015

- Published8 July 2015

- Published8 July 2015

- Published8 July 2015

- Published8 July 2015