The jobs recovery takes shape

- Published

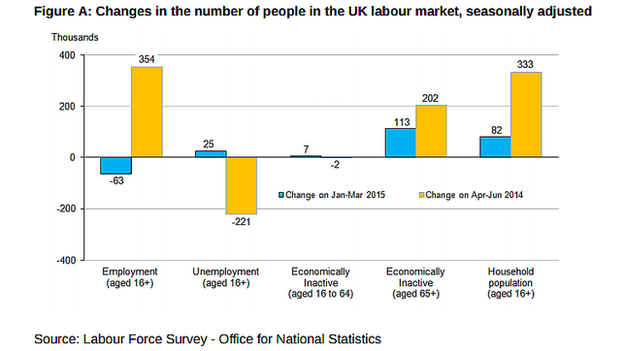

New job figures from the Office for National Statistics show a mixed picture, of UK unemployment rising in April to June, Scottish unemployment falling more than anywhere else, yet Scottish employment also falling.

The past year has seen strong jobs growth across Britain, but the picture looks like a slow-down in job market recovery if you compare the latest figures with the first quarter of last year.

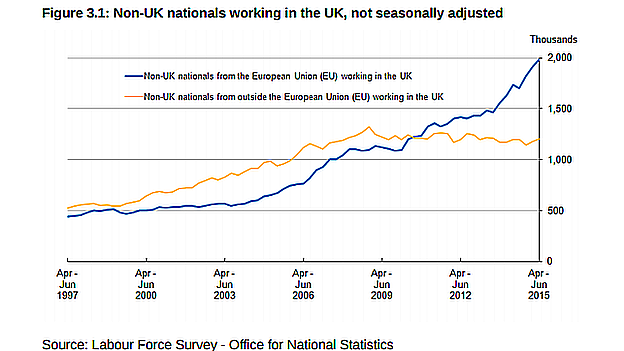

But there's lots more behind the figures. Take, for instance, the big picture of migrant workers. The Office for National Statistics has put a special focus on people who are not UK nationals. It tells us that nearly 2m people from elsewhere in the European Union are working in the the UK. That's nearly doubled in the past five years.

The initial effect of the recession was to reduce opportunities for foreign workers in Britain, and a lot of people headed back to Poland among other homelands. But as Britain has since seen a lot more jobs generated than elsewhere, people have come back.

Poland and the other new entrants to the EU from 2004 account for around half of the EU total. Others have come from the most troubled EU economies with high unemployment, such as Spain and Greece.

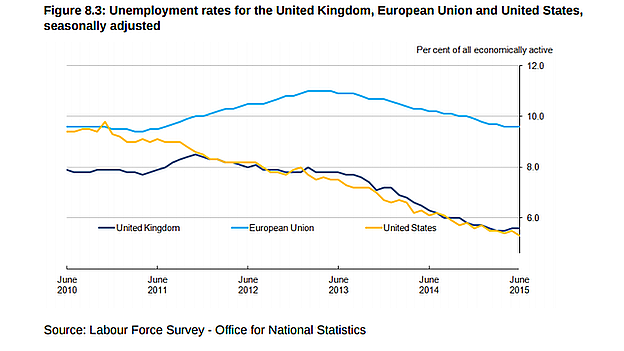

The eurozone unemployment rate is now falling, but it's a lot higher than the UK's. And if you look at the ONS report, you can see how much the UK has come to run in parallel with with the de-regulated labour market in the USA.

Those working in the UK from outside the European Union - most of whom need a work permit - have fallen from a peak in early 2009 at the worst of the financial crunch, and have stabilised around 1.2m. That probably owes a lot to the immigration and work permit squeeze applied by the government that came to power in 2009.

The share of the workforce that is now taken up by non-UK nationals has risen over the past 18 years by nearly three-fold. More than one in ten UK workers are not UK nationals. The ONS figures don't show where the largest share is, but you could guess it's going to be in and around London.

The number of people who were born outside the UK and are now working in the country is close to 5 million. That is because around 1.8m workers were born abroad, and were then or have become UK passport-holders. That's nearly one in six in the workforce.

How you interpret these statistics is down to your perception of immigration. Either these are people doing jobs that resident UK people should be trained to do, and perhaps their presence is a brake on wage growth, or the British economy is benefiting from its flexibility and proving a very attractive place for others to come and work, bringing their skills to help grow the economy for everyone's benefit.

Many big employers would like more flexibility to bring in skilled workers from outside the EU, including those who have recently graduated from UK universities.

Either way, these numbers will weigh heavily on the referendum debate about Britain's place in the European Union.

Part-time and temporary

If you take the Scottish figures, and look under the bonnet of the jobs market, it can tell you a bit about the way employment is changing as things are slowly repaired from the car crash of the downturn.

For instance, the year to last March saw an acceleration in the growth of self-employed Scots - up by 10,000 on last calendar year, to reach 311,000. Yet if you look further back, it's not grown by much over the past two years.

There were 1.86m full-time workers, growing slightly faster in the year to March than part-time workers, which were around 700,000. There's been a rise to 100,000 in the number of Scots with second jobs (three out of five of these are women) and 133,000 temporary workers.

Is temporary work because these people could not find full-time work? That's true for many, but fewer than half the total.

And do 700,000 part-time workers want to work full-time but can't find a job? Fewer than you might think - just above 100,000. Some 440,000 of them did not want a full-time job, including students and those with child caring responsibilities.

Youth and claimants

Scottish youth unemployment (aged 16-24) fell below 15% in April to June. It was nearly 21% at peak. In Spain, it's been around half.

The chance of getting a job if you've just left school as early as you can is significantly higher if you're female. Employment rates for 16 and 17 year olds are 28% for young women, and 21% for young men.

And then there's Jobseekers Allowance (JSA). The criteria for being eligible has been changing, which skews the figures. But it's worth noting how low the claimant count is. The July figure was under half the number who were found to be seeking work in the most recent labour market survey.

Of the whole workforce, 2.6% were on JSA. That is comprised of 3.4% of men aged 18 and over, and only 1.7% of women. The more concerning figure is that quarter of them had been on JSA for more than a year, and that goes for more than one in ten of claimants aged up to 24. Of the 16,000 people in their 50s on JSA, more than a third are long term unemployed.

They're competing for jobs with a growing number of older people staying in the workforce past the age of 64. That's seen significant growth up to 80,000 people. One in nine men on the state pension is also in employment.

The ONS doesn't say if it's because they want to be, or because they have to be.

- Published4 August 2015