Putting money on Indyref 2

- Published

It was the economy wot won it, and lost it. On identity, emotion, enthusiasm, optimism, organisation and so much more, last year's referendum on independence was heavily weighted in favour of the "Yes" side.

But on the economy...? Well, the debate rages on, but the polls tell us it was the economy that made the difference.

Was it the Better Together's strategy of Project Fear?

Post financial crunch, was this the wrong time to ask Scots to take a financial risk? Or conversely, were enough Scots financially content with their lot, under the constitutional status quo?

Did the "Yes" campaign perhaps fail to pin economic failure on Westminster?

Or could it be that the economic prospectus for independence - however many pages there were - just wasn't very convincing?

A year on, while most on the "Yes" side reflect on what might have been, speeches that might have been delivered, and on claims of broken promises, several supporters of the independence cause are challenging the notion that the "Yes" campaign got the economic case correct.

It may not matter if September 2014 were to have been the end of the debate. But clearly, it's not.

And as attention focuses on the prospect of another vote - indyref 2 - there's a choice between the "one more push" school of campaigning ("all that energy and rivals' weakness will get 'yes' over the line"), and the question of how to ensure the messaging works better next time. That might require a significant re-think.

Sterling effort

Here are two issues. Neither will surprise you.

First, currency. No, it hasn't gone away. Neither nationalist veterans Gordon Wilson or Jim Sillars think so. Nor the Scottish Green's Patrick Harvie, nor Yes Scotland chief executive Blair Jenkins. (Or anyone on the "No" side.)

There were two points on this early last year which may have been crucial for the course of the campaign.

One was a speech in which Chancellor George Osborne said the rest of the UK simply wouldn't do a deal with an independent Scotland on sharing control of the pound sterling.

His speech is widely perceived as having backfired. Even if some people believed him, the tone was portrayed as "bullying". For the "No" side, that was a big problem. That "no deal" message had previously been seen as the trump ace.

The second point came soon after. An anonymous minister was quoted in a report in The Guardian saying that "of course Westminster would do a deal" after a "Yes" majority - it simply couldn't be admitted before the vote.

Plan Bs

A prominent SNP member has told me that unattributable briefing to the Guardian "was possibly the worst thing that happened to us".

It meant that SNP leader Alex Salmond had a weapon with which to counter-attack, not just against Better Together but against those on his own side who had doubts.

The unnamed minister, giving one unattributable briefing, was cited every time the currency issue was raised.

It allowed the "Yes" campaign to go into the leadership debates and final stages without a Plan B, and then with several Plan Bs.

When it came to post-referendum negotiations, it was argued that Westminster would admit what was in its interests. If it didn't, then Scots could refuse to take on a share of the debt. Either way, everything would be all right on the night.

"Difficult"

Nicola Sturgeon concedes the currency issue was "difficult". She correctly observes that there was no alternative position without difficulties. But she made it clear that she is open to a new approach.

The most coherent argument would be to say that, if Scotland voted for independence, then that would require an independent currency.

Any sharing of control over currency would significantly undermine notions of independence, and tip control towards the larger, more powerful partners. (If in doubt, ask Syriza in Greece.)

But to tell Scots that their pay, pensions, savings and loans would be denominated in a new, unknown currency would be a hard political idea to sell to voters, particularly while sterling retains credibility. Their employers would require convincing too.

A new proposition is required. Senior nationalists are attracted by the idea of making a shift to support for an independent Scottish currency. But they know they will have to start making the case for it sooner rather than later. Voters would need time to get used to the idea.

Brent crude

Another issue: oil. Everyone ought to know it has more than halved in price since summer of last year.

Remember the claims that Scotland's oil was worth £1.5 trillion, and that 24 billion barrels could be recovered? They were exaggerated last year. They won't wash again.

Reserves, at wholesale prices, are worth less than half that. The cost of extracting them will leave far lower profits than before, and the finances of extracting even half of those 24 billion barrels look a lot less convincing.

Trade body Oil and Gas UK recently published an economic impact report pointing out that much of that figure is made up of reserves that are yet to be found, and another big chunk is made up of reserves that have been found, but are not commercially viable.

That accounts for 300 finds in UK waters, totalling nine billion barrels. Most have been known about since last century, but they haven't been financially attractive, or at least viable, even with the price of a barrel of Brent crude above $100.

Icing on the cake

But, we're now told, offshore oil and gas was never vital to the Scottish economy. We can match the UK's output without them. It is, as some claim, "the icing on the cake".

Is that true? Well, it appears to refer to the output of the onshore economy, not including the production from offshore fields of oil and gas.

Using comparable figures, in 2012, Scotland had output per head of £20,000 while England had £21,900 (Wales on £15,400 and Northern Ireland on £16,100).

Bear in mind, however, that using numbers that ignore offshore oil production does not mean the sector doesn't matter. Onshore support services for oil and gas do count towards Scotland's economic output. They are the major part of the employment impact of the offshore industry.

Oil and Gas UK recently said the total of people directly employed, plus those in the supply chain, plus those whose jobs depend on spending of direct and supply chain employment, came to a total 375,000 UK jobs.

That's 65,000 down on last year, but still a big figure. And the economic model has previously suggested that 45% of those jobs are in Scotland.

Now, a lot of that employment is successfully transferring to export markets. But a lot of roles remain dependent on the UK offshore sector.

So on that basis, we could assume something between 100,000 and 180,000 Scottish jobs are dependent on the offshore industry, and many of these are high-skill, high-paying jobs. If that's icing, then the underlying cake looks significantly smaller.

Balanced books

Can Scotland do without offshore oil and gas? Put simply, yes, it will probably have to. Eventually. And if the low price hits the upstream parts of the economy, it's a windfall gain to those who have to buy the stuff. So the oil-consuming economy should be helped while oil producers suffer.

The problem with the argument lies not with the economy as a whole but with public spending. If Scotland is to become more fiscally autonomous, it needs something to replace oil revenues if it is to balance government's bills.

Scotland's onshore tax contribution per head has nearly matched that of the whole UK in recent years. With a geographic share of offshore revenues, it has been higher. But as we can expect much lower offshore revenues with which to balance the notional national books, Scotland's public spending habit is a challenge.

In 2013-14, for each £100 spent by government on the average person in the UK, there was £110.80 spent on the average Scot.

Even if there were a return to a higher oil price, recent tax rate cuts and low profits mean government could have little expectation of a return to the huge tax bills levied on oil and gas producers as recently as last year.

And if a more autonomous Scotland were to sustain its spending profile per head, it would face a very much bigger government deficit than the rest of the UK.

That could be handled either by spending cuts, tax increases or more borrowing. None is an easy option.

Demographics

Political pundits point to a second independence referendum early next decade. Some are even willing to name the date, in September 2021.

It would be a fool who predicts where the oil price will be by then, but wise heads might work on the assumption that tax receipts from production will be much lower than we've been used to.

The George Osborne austerity years may be behind us, if the forecasts he's using are any guide.

But then, the Institute of Fiscal Studies points out that as big a squeeze on public spending will be required if we are to adjust to the challenge of demographic change. The only difference is that it can be phased, probably, over a longer period.

Euro recovery?

By we're looking to 2021, sterling may have succumbed to the pressures from the UK's trade imbalance, and have less appeal to voters. Or maybe not. It's been remarkably resilient through tough times.

The Euro may look much more attractive than it's looked in recent years. Or it may have frayed at its southern edge.

Holyrood will, by then, have new powers to raise or lower taxes. As Prof David Bell of Stirling University has pointed out in recent days, it looks like income tax will be the main lever available to ministers.

That power shifts to Holyrood starting from next April, but Nicola Sturgeon is leaving ever stronger hints that she has no intention of varying tax rates next year.

Interviewed on Reporting Scotland last Friday, she highlighted the inability to vary rates differently on lower, upper and top bands. The implication: she only wants to use tax powers if she can use them to alter the proportions paid.

It looks likely, by around 2021, that there will be that flexibility to redistribute from high earners to low.

But Prof Bell has an observation which ought to send a chill through government financial planners.

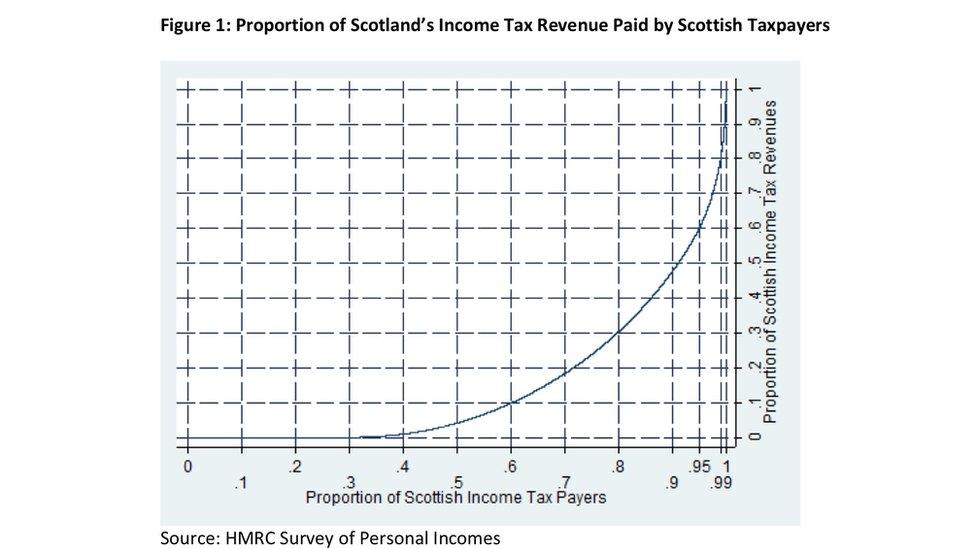

Only slightly less than the UK as a whole, Scotland depends disproportionately for its income tax receipts on high earners.

You may not think high earners pay enough. You certainly wouldn't be alone.

But this analysis (commissioned, as it happens, by one of Scotland's richest men, Sir Tom Hunter) shows the highest-earning 10% of taxpayers contribute more than 50% of the total income tax take. The highest-earning 5% contribute more than 40%.

That 5% equates to only 130,000 people. "A large proportion of that revenue is dependent on a relatively small number of taxpayers," writes Prof Bell.

"So how this group reacts to changes in tax rates will be very important for the health of the Scottish economy."

And if high taxes can be avoided by a move across the border, it won't take many to move to Berwick or beyond before another sizeable hole opens up in Holyrood's budget planning.

But then, if the Prime Minister in 2021 is Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn... ?