What can be done to save steel jobs?

- Published

Tata Steel employs about 400 people in Scotland, including about 350 at the Dalzell plant in Motherwell

Hundreds of workers at Dalzell in Motherwell and Clydebridge in Cambuslang have been told they are losing their jobs.

At a meeting this morning, Tata Steel confirmed claims from union sources which were first reported on Friday.

Tata said it would close its two plants in Scotland with the loss of 270 jobs - 225 at Dalzell and 45 at Clydebridge.

The move comes after the coke ovens have already cooled in Thai-owned Redcar, much of Capuro industries has gone into administration, and Scunthorpe - heavily dependent on steel - has also taken the brunt of today's Tata announcement.

In these circumstances, governments want to look busy. The UK Business Secretary was exiting a summit in Rotherham as the Tata Steel reports surfaced. Nicola Sturgeon has promised a task force. No stone will be left unturned, etc.

Both governments will be pressured by Labour, in opposition, which ought to know how little ministers can do.

Urgency

This can be played out for party political advantage. Or it can be seen in a global context.

Britain's steel competes in a worldwide market. It has successfully sought out high-value, high-quality markets, and become much more efficient than in the days when 200,000 were employed in it.

But it faces three major disadvantages. One is that China is accused of dumping cheap, subsidised steel into western markets, because demand for China's vast output has dropped sharply with the nation's downturn. It is reckoned that China's overcapacity is roughly double the entire output of Europe's furnaces.

Chinese President Xi Jinping is due to hold discussions with David Cameron

So the timing of Indian-owned Tata Steel's announcement will put more urgency into David Cameron's discussions with the Chinese president today, as he starts his state visit to Britain.

While asking for lots of investment in infrastructure and co-operation on trade, the Prime Minister has to put what pressure he can on his visitor to pull back on cheap steel.

Expertise

The UK government can also take action to offset the high cost of electricity, but within the constraints of state aid rules and its targets on climate emissions. And the industry complains that business rates are far too high.

Ministers could go out to find new customers for British-made steel, but such customers will be more attracted to cheaper steel made in remninbi or euros.

Or they could find a buyer. Tata Steel had a buyer for its European operations last year - Klesch Group, controlled by Gary Klesch, a steely American billionaire.

He wanted Tata's expertise, particularly in railways, and its reach into European markets. And he argued that his business model worked better in a bear market.

Not well enough, though. Although from the Land of the Free and the free market, he now says he pulled out of the deal because the British government didn't seem interested in helping with energy costs or Asian dumping.

Sterling

And then there's sterling. Foreign travel looks relatively cheap, as do imports. And that means it is more difficult for British firms both to export and to compete with imports.

There are several reasons for sterling being strong against most currencies. The main ones revolve around decisions taken on monetary policy in the Bank of England.

It's worth noting that the Scottish government is going easy on that monetary policy. Unlike Alex Salmond in opposition days, the Bank of England is not being given the blame for allowing sterling to become so strong.

Why? Perhaps because the SNP has yet to find a new policy on relations with the Bank of England, having become mired during the independence referendum campaign in the currency argument and joint controls over the central bank.

Different voices

Instead, it is Labour's new shadow chancellor, fresh from a humiliating U-turn on fiscal policy, who has announced an approach to the Bank of England which steals from the SNP policy book.

John McDonnell is saying that the key rate-setting committee in the Bank of England, the monetary policy committee (MPC), should be reviewed.

While making it clear he wants to see the MPC remaining independent (something that wasn't at all clear before), he's got a former member, Prof David Blanchflower, to carry out a review.

Along with a call for a broader remit than solely an inflation target, the ideas being floated include the appointment of people from outside the City of London, with perspectives from Scotland and the English regions. All that and gender balance too.

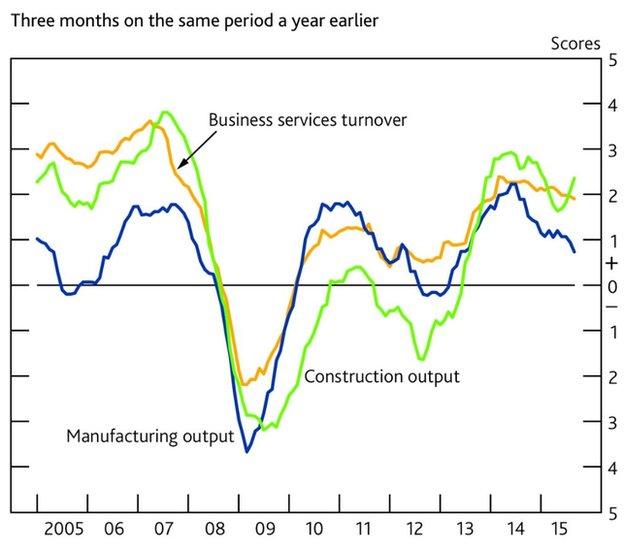

The Bank of England already has a network of "agents" around the country, including one in Scotland. They published a "summary of business conditions", external at the end of last week.

It showed that the Bank has, at least, clocked manufacturing is suffering from the strengthening of the pound.

Business Activity

So here's one question for Professor Blanchflower's review: if there were different voices around the MPC table, what difference would their non-London perspective make to decisions, as they affect women, nations and regions, the manufacturing and exporting sectors, and to the steel industry?

- Published14 October 2015