Who is trade for?

- Published

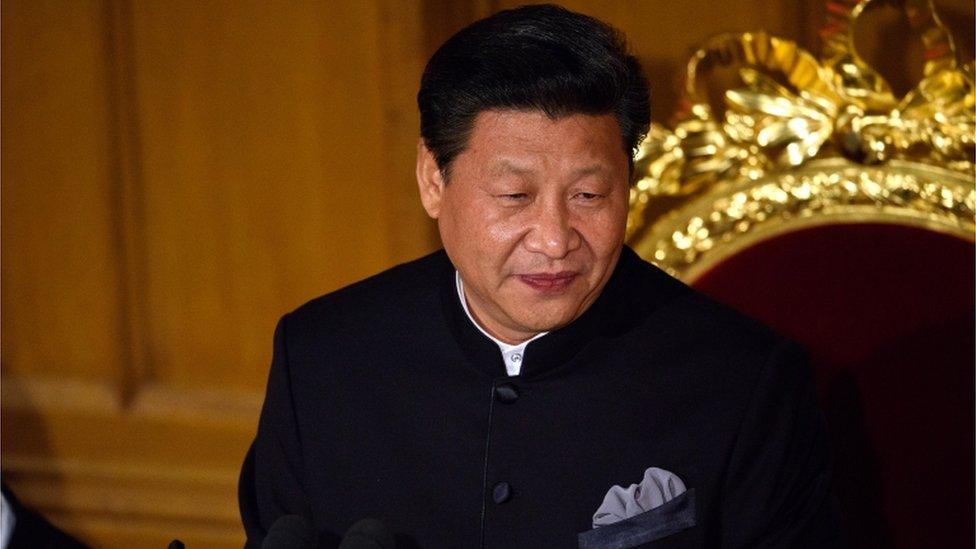

President Xi's visit to the UK has highlighted the importance of international trade

The Chinese president has hit town with more than £30bn of trade and investment in his brief case. That's while his subsidised steel firms are playing a significant role in pushing British workers out of thousands of jobs.

So this is an interesting time for the governor of the Bank of England to weigh in with his thoughts on the economics of trade and open economies.

Mark Carney was delivering a lecture in memory of one of Scotland's finest economists, Sir Alec Cairncross. He used it with an attempt at quite subtle influence of the debate on Britain's future in or out of the European Union.

The structure sought to balance the pro-membership side (growth, dynamism, low inflation) with the anti (exposure to risk and shocks from European partners).

This was dry economics. The governor didn't have to worry low inflation is achieved by open border worker migration. That lowers the cost of skill shortages when, for instance, Britain needs to recruit Polish engineers for its fishing boats, or nurses for its health service.

The Bank of England governor doesn't have to answer to workers who feel aggrieved at immigration.

'Don't box in Britain'

As a balancing act, it wasn't that convincing. This was a speech that seemed to leave the 'remain' side with quite a lot more material to work with.

One side of the argument was retrospectively reflecting on a relationship with Europe which appeared to have few downsides, if any.

On the one hand, on the other: the governor sought to deliver a balanced assessment

What he didn't quite spell out, but strongly implied, is that all the talk of regulation from Brussels hasn't stopped Britain from being one of the most business-friendly and competitive major economic powers in or out of the EU.

The more Euro-sceptic element was looking forward to what European regulation might do to Britain's financial sector. The warning was clear: don't box in Britain.

It continued: while you euro-users need new rules to get the eurozone working better, don't forget those EU members that are outside your club.

Mr Carney wants to see formal recognition of a union "with multiple currencies and multiple risks". That chimes happily with the Prime Minister's agenda for reform.

Trade and values

In Brussels, there are efforts to respond to criticism from Britain and to make life easier for those campaigning to keep the UK in the union.

As part of that, a new approach to trade was published last week. This matters because all of Britain's formal trade negotiations - including complaints about dumping of subsidised Chinese steel - have to go through Brussels.

The review is not all about Britain. Far from it. It is partly to respond to the changes in the way the world economy works, introducing extremely complex cross-border trading of ideas, technology and the people with the skills, particularly in the digital economy.

The EU believes trade must be shown to benefit the people of Europe

It is partly to adjust to the interests and capabilities of smaller businesses, which have fewer resources for pushing into foreign markets, overcoming barriers to trade and complying with regulation.

It is partly also a response to public pressure over the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, or TTIP - that is, negotiations between the EU and US which have met strong political opposition within Europe.

It summarises that opposition as challenging Europe's leadership with the question: "who is EU trade policy for?" The answer now being offered is one that is not just about growth, jobs and innovation, but about fitting with Europe's social values.

That means ensuring that competition with other countries does not undercut European jobs with exploitative labour practices or environmental degradation elsewhere. There's also a promise to be more open than some recent deals have been.

Where trade forces 'globalisation adjustment' (that is, workers in Europe lose their jobs because of lower-wage competition from outside), the Commission wants to extend the reach of its compensating fund.

It concludes: "Trade is not an end in itself. It is a tool to benefit people."

New deals

The 'leave' side of Britain's debate about Europe is keen to form new trade relationships. Some want to see re-orientation to an emphasis on links with the Commonwealth. But with patterns already established that are heavily loaded towards nearer neighbours across the North Sea, a trade deal would also have to be struck with former EU partners.

What that side of the debate has to explain is how to negotiate those complex deals very soon after departing the EU, and how to negotiate them better.

The outcome of trade talks tend to reflect the relative power between them. Having a market of 500 million people gives Brussels negotiators clout.

When New Zealand negotiated a deal with China, and Australia with the US, it was a rather different story.

As we saw with last year's referendum on Scottish independence, the vision of a different future can become confused and obscured by the difficulty and cost of the transition involved in getting there.

- Published21 October 2015

- Published21 October 2015

- Published21 October 2015