Is there a doctor in the house?

- Published

The National Health Service has been described as the closest thing Britain has to a state religion.

It's politically untouchable and its budgets ring-fenced (though the fences sometimes need mending) because it has overwhelming public support.

But if it's a state religion, it's got a problem with recruiting its priesthood. And a lot else besides.

Audit Scotland has issued an update on its views of the NHS north of the Border. It makes uncomfortable reading for health secretary Shona Robison about targets missed for waiting times.

It adds urgency to those calling for a re-think of how NHS Scotland needs to reform (now including government ministers), under pressure from tight budgets and growing demand for its services.

The spending watchdog notes the high-level plans for the NHS adapting to changed demands. But it also highlights areas where not much progress has been made towards the vision.

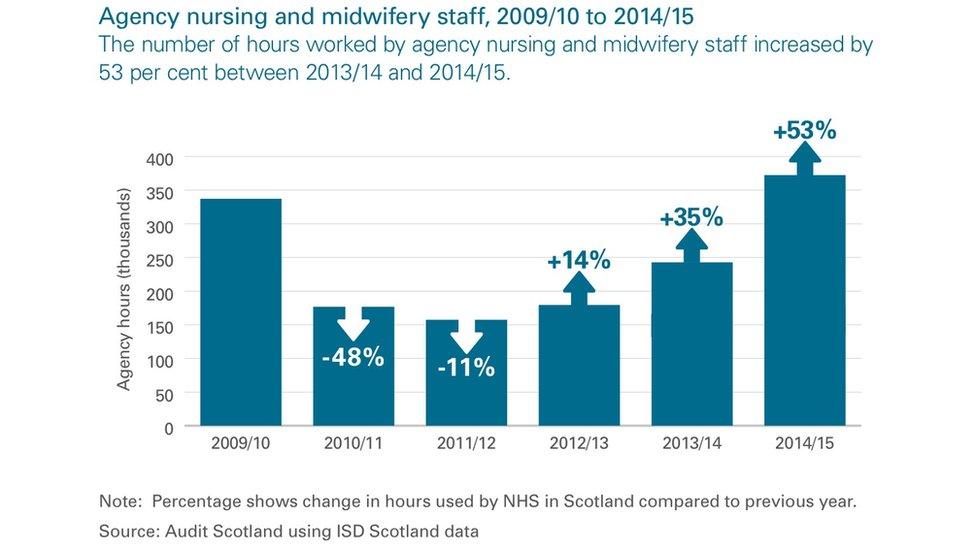

A key element of it is a warning about staffing levels, high vacancy rates and the sometimes astonishing and rising cost of plugging gaps in rotas.

Audit Scotland has set government and health boards the task of assessing the changing demands for staff - for instance, as medical technology changes, and care is shifted into patients' homes.

And even if enough people are trained for changing roles, there's a big challenge to ensure they're in the right places, they're retained in the workforce, and in Scotland, and that they're motivated to deliver the expected rising quality of care.

Workforce

That issue of workforce planning is not the main area of party political ding-dong about SNP stewardship of the health service. But it is worth a closer look.

I'll spare you the detail but, of late, I've had more exposure to the NHS than I would have wished. I've found that doctors and nurses, when not doing a (usually) fantastic job, laugh scornfully about the notion of 'workforce planning'.

The Scottish government can produce much evidence of plans, work programmes, flow charts and effort going into projections for the future needs of the NHS. But there's not so much evidence that it's feeding through to have much practical effect.

Audit Scotland gave a lot of weight to its call for a more co-ordinated approach and better data with which to plan. It's hard to believe that health boards don't co-ordinate recruitment, but they don't.

The numbers are big. One in ten people in the workforce are in the health or care sectors.

Nearly £6bn is spent on pay for 137,600 NHS jobs in Scotland. Actually, there are more people on the payroll, but this is a measure of "whole-time equivalents" - the number of employees if they were all full-time. Nearly £1bn is spent on national insurance and pensions.

There are 59,000 nurses and midwives, or 43% of the total. Medical and dental (including doctors) number 12,500, or 9%. There are twice as many administrators as medics (and if you think they're all about red tape and waste, try making an appointment with a doctor without using a secretary or receptionist).

Payroll churn

Let's stick with the numbers, because that's how to get a handle on the problem.

Almost a fifth of staff are aged over 54, and that has been rising. Of general practitioners, 34% were aged over 50 last year, up from 28% ten years ago.

Turnover of staff last year was at nearly 7%. Among doctors and dentists, it was at 9.2%. In the islands and rural services, the churn of staff is higher still.

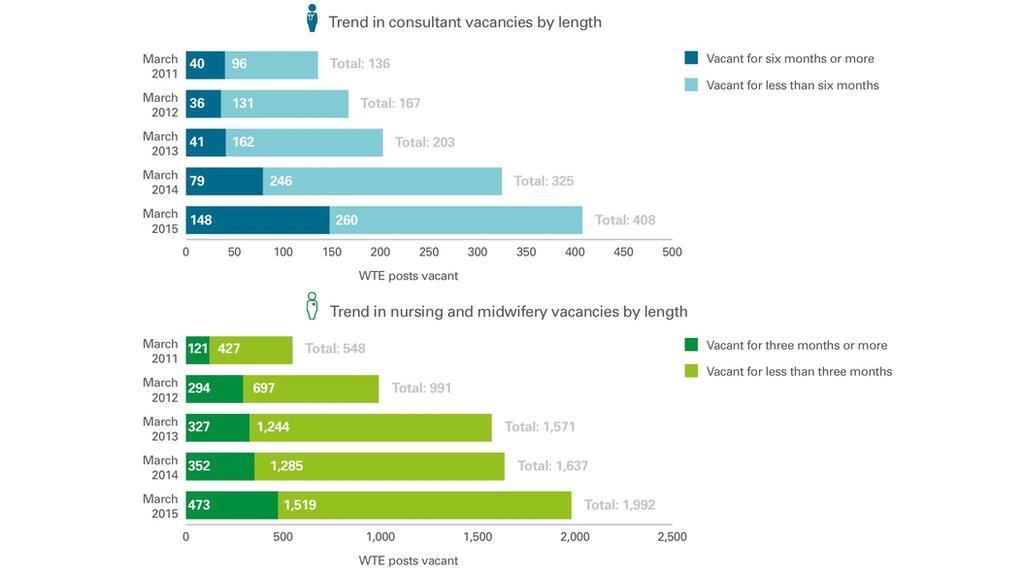

Vacancies for consultant posts have been rising steeply, up from 235 in March last year to 408 this year. Among senior posts for general acute medicine, one in six was being advertised in March. In radiology, it was one in eight.

From my anecdotal evidence, doctors are opting to retire or go part-time because they dislike the direction of travel of their contracts - 12 hour shifts, weekend working, or seven days on call, even for the most experienced as they are nearing retirement.

They are able to work part-time partly because they are so well-paid. Even doctors (privately) admit that consultants and GPs won far too much over the past 15 years, as NHS negotiators bought them out of private sector work that few of them were doing.

Mobile nurses

These challenges are not just down to the NHS in Scotland. Or to put it another way, it doesn't exist in a vacuum.

The workforce is mobile - in and out of the labour market, and in and out of both Scotland and the UK.

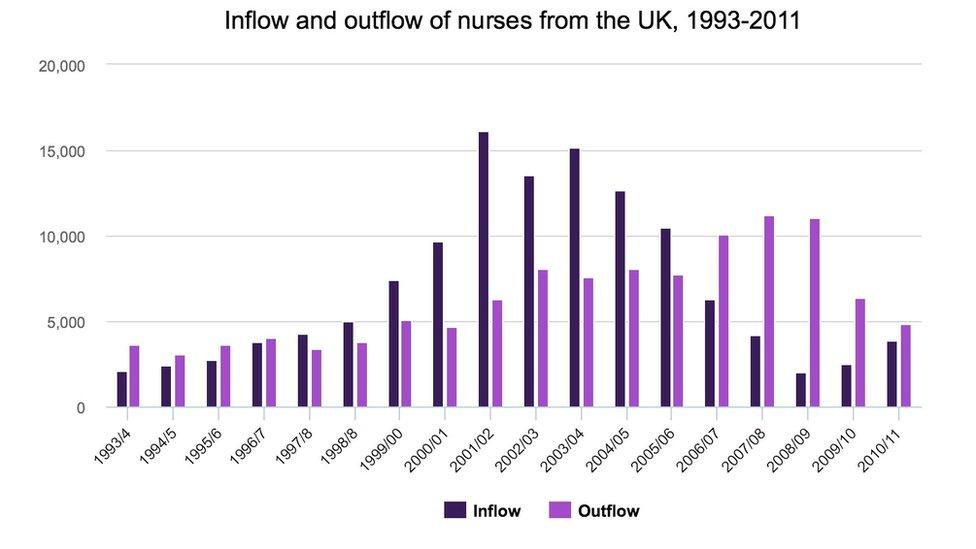

For all that people complain about the need for health boards to recruit nurses overseas, it wouldn't be necessary if nurses trained in the UK (at taxpayer expense) weren't taking their skills to foreign countries.

According to the Royal College of Nursing, more UK-trained nurses left the UK to work abroad in 2011 than foreign-trained nurses came in this direction.

And there's a demographic challenge. An eighth of nurses are aged 55 or over. Nearly half of midwives are eligible for retirement in the next decade.

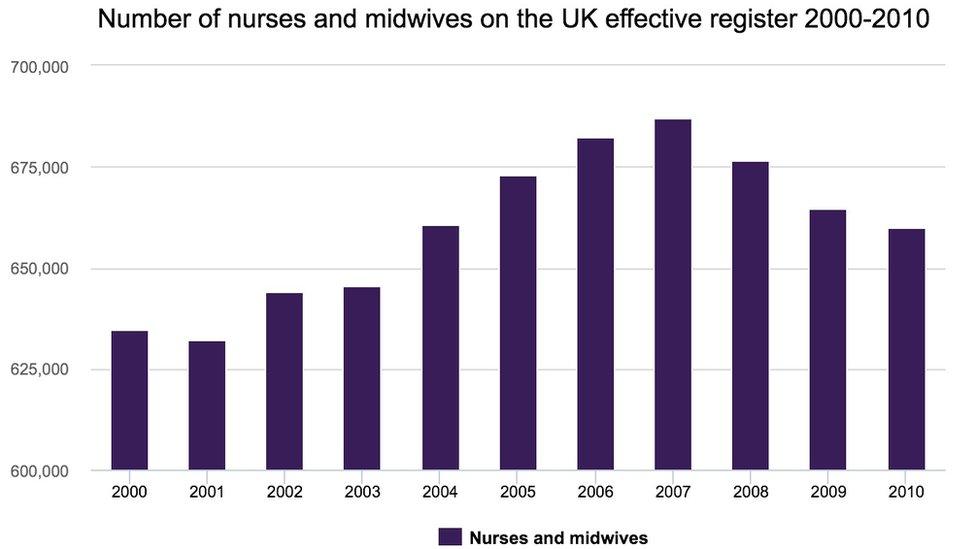

And although a lot more nurses have been trained recently, there has been a decline in the number who are registered in the UK.

Foreign physicians

Britain is also reliant on foreign-trained doctors. In the 1970s, quarter of registered doctors in the UK were trained elsewhere. By 2005, it had risen to a third.

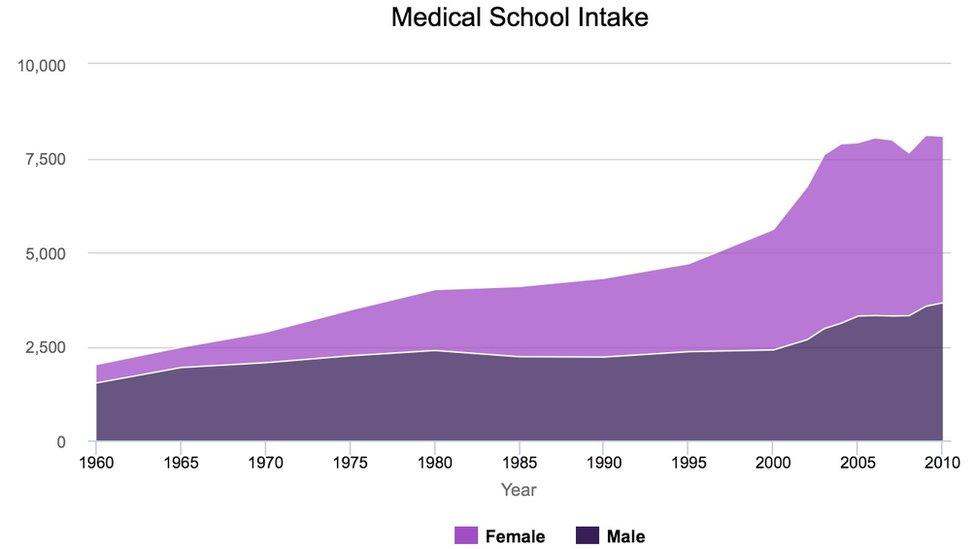

That growth rate slowed with the expansion of Britain's medical schools (places up by 70% since 1960 to reach nearly 6000 graduates each year). By 2012, 37% had been trained overseas.

The NHS requires far more hospital doctors than it used to - up 30% to 143,000 across the UK in the past decade.

The problem identified there by the King's Fund, a London-based health policy think tank, is not so much the demographics of large-scale retirement over the next decade, but the reverse - a shortage of career development opportunities for younger doctors, as senior consultants work past conventional retirement age.

And just as British-trained nurses are sought in other countries, so too with doctors. The King's Fund points to analysis suggesting that the USA will need 130,000 more doctors ten years from now.

Who cares?

In social care too, demand is on the rise and Britain is dependent on foreign-born people to do a lot of the work.

In England, nearly a fifth of the social care workforce is from outside the UK, and in some parts of the south-east, that can rise to half.

While 1.6 million people work in social care, the projections are for that to rise by at least a third within ten years.

Flexible women

The social care workforce is 80% female. That goes for around 90% of those at the front line.

And that is one of the trickiest bits of NHS workforce planning too. It's increasingly a service delivered by women.

As women still take the burden of family care, HR departments have to adapt to their requirements for flexible and part-time working.

Around 70% of those starting medical degrees are female. It takes ten years for one of them to become a fully qualified GP.

Plugging gaps in specialisms with that long a delay is only exacerbated by the changing protocols of how healthcare is delivered. Decisions made now about the workforce needs in five to ten years won't necessarily meet the evolving health requirements of next decade.

Medical science moves fast. Some skills become redundant. Others will be required of which we haven't yet heard.

Some time between 2017 and 2022, there will be more female doctors in the NHS than male.

Assuming many women doctors will require maternity leave, and may take career breaks, that makes workforce planning a lot more difficult.

So you've got to have some sympathy for those charged with workforce planning in the NHS. It's not easy. But as Audit Scotland points out, it could be a lot better.

- Published21 October 2015

- Published21 October 2015

- Published21 October 2015