Steel yourself for an industrial strategy

- Published

There's a retro vibe afoot: the planned mothballing of two steel plants in Lanarkshire brings back the 1980s as if it were... well, 30 years ago.

Thousands upon thousands of local council jobs look like getting the axe due to the spending squeeze, yet 270 jobs rolling steel slabs get a task force, all hands are on deck to find a buyer, while the opposition calls for nationalisation.

It's not hard to see why. Nostalgia is part of it, these being the remnants of a once great and noble industry, around which large parts of Lanarkshire was built.

It's partly because Clydebridge and Dalzell are symbolic of the impact of globalisation, forcing transition on workers and communities at a local level as the price of enriching the broader economy.

Other parts of Britain and Europe feel the strain of in-migrating people. In Motherwell and Cambuslang, the concern is about out-migrating jobs.

But it's also because there's discomfort that the new economy and the new labour market is unplanned and haphazard, buffeted by market forces and lacking in the security of big plants with jobs-for-life.

March of the makers

It is not always easy to appreciate that Britain has grown quite successfully in recent years by retreating from the making of things.

The service sector makes up 75% of the economy, and while it ranges from high-value finance and professional roles to burger-flipping and care homes, it lacks that noble quality with which the old heavy (and dirty) industries are seen in hindsight.

There is widespread agreement that Britain needs to think again about manufacturing. On the freer market end of things, George Osborne coined the evocative ambition for there to be a "march of the makers".

The rhetoric hasn't always matched the policy outcomes. Industrial policy at Westminster now consists of a push towards a more technically literate workforce, and incentives aimed at 11 chosen sectors, ranging across aerospace and automotive to nuclear and wind power, life sciences and professional and business services.

There are also 'catapult centres' for propelling ideas towards the market in robotics, synthetic biology and better batteries.

If you want to see what British manufacturing looks like these days (under German management and with a lot of robots), I'd highly recommend 'Building Cars Live' on the BBC iPlayer for two more weeks. We could do worse than make it required viewing for all secondary school pupils, particularly those with a bad experience of work placements.

Intervention

Meanwhile, the recent success of Jeremy Corbyn in winning the Labour leadership points to a desire, in some quarters, for a more interventionist government, willing to take control of strategic industries to serve a social purpose in addition to the shareholder one.

So is this time to think again about an industrial policy? Even the Confederation of British Industry, which was closely aligned with the free market orientation of recent governments, wants to see a lot more intervention.

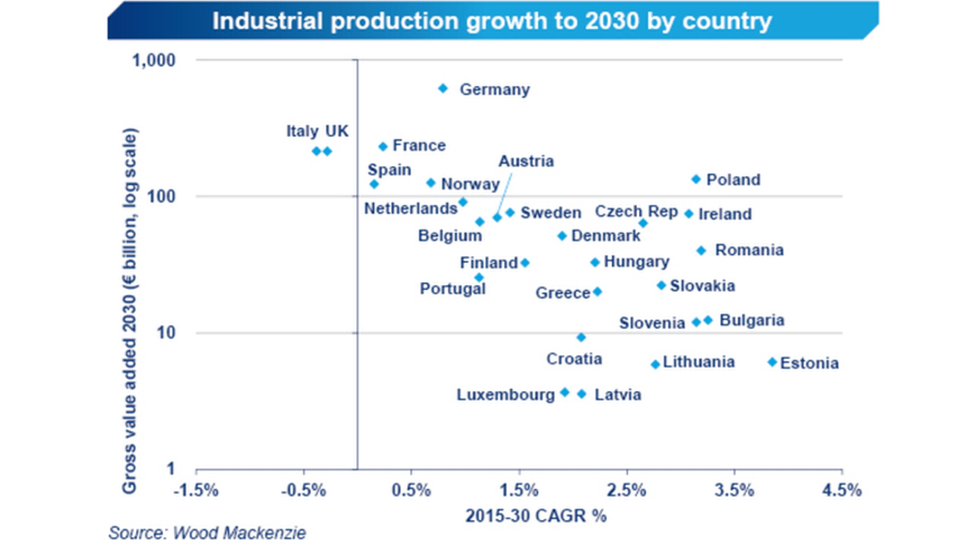

Without it, Mr Osborne may find the makers are marching backwards. Wood Mackenzie, the economic consultancy based in Edinburgh, this week issued its projection of future manufacturing sectors in Europe.

Largely because oil and gas is in decline, it showed Britain as one of only two countries, with Italy, where production is on track to decline.

In the 1960s and 1970s, industrial and regional policies went hand in hand, and got themselves a bad name. In the Sixties, Harold Wilson's Labour government picked industries and locations for them that had more to do with rising unemployment and politics than financial viability.

Ravenscraig had already been chosen as the heart of the steel industry in Scotland. There had been clear advice to locate a new, integrated steel works near a deepwater port, for import of iron ore and export of the steely stuff.

Colvilles, the firm that dominated Lanarkshire steel-making before nationalisation, thought differently. So did the government. Because steel workers were already in Lanarkshire, it was required that the new steel works should be where the steel communities were. The iron ore should come to them, which until 1978, meant small ships unloading at a rail terminus in central Glasgow.

The government wanted a strip mill to supply the industries it wished to see develop in Scotland. It decided that the plan for an integrated strip mill should be split between Scotland and South Wales.

What's worth noting about this is that the Prime Minister who made the announcement was Harold Macmillan, a Conservative.

It's also worth a brief pause to wonder if the 'Craig steel works had been located at Grangemouth or Hunterston, requiring the workforce to move, the rest might not have been consigned to Scotland's industrial history.

Lochaber no more?

Other big industrial plants from the 1960s came and went. Linwood car plant and Bathgate trucks and buses are "no more", as the Proclaimers' song goes, or at least they are utterly changed, into a retail park and commuter housing.

In the Highlands, Invergordon in Easter Ross, and Corpach, near Fort William, joined Dounreay as the government's designated industrial hubs. Neither aluminium nor paper were to perform as hoped at the two ends of the Great Glen.

But as 1 November 2015 is the 50th anniversary of the Highlands and Islands Development Board starting its work, it is worth noting that this government response to de-population and decline was the starting point for a highly successful renaissance of the whole region, even without big industrial plants. "Lochaber no more"? No more. And more on that before long.

Inept interference

In the 1970s, industrial policy became associated with nationalisation of old, loss-making industries as they lost markets to more efficient competitors far away.

Poor management, terrible industrial relations and inept political interference gave intervention and industrial policy a bad name.

And that was the launch pad for the market-driven 1980s, replacing the old industries with the service sector, and especially finance. Not only were the old heavy industries privatised, but so were the new ones. The government stake in (at that time) the young industry of offshore oil, was sold off.

Contrast that with our North Sea neighbour. For all the talk of Norway's enormous fund from keeping the proceeds of North Sea oil, there's little discussion now of how much better Norway has done by holding on to a very large portion of the equity in its offshore assets, as well as its tax take from them. Statoil is anything but a lumbering nationalised dinosaur.

Old industries

Other European countries have done significantly better than Britain at transforming old industrial heartlands. That's according to Professor Andrew Cumbers at Glasgow University, whose research into Germany, France and the UK makes uncomfortable reading for the economic departments in Whitehall.

They chose the strategic manufacturing industries they wanted, and made sure they were protected and provided with investment.

This was not with simple subsidy for losses incurred, but with state-controlled industrial investment banks, willing to take the long view with much cheaper and more attractive lending conditions than UK firms. In Germany, these banks were usually regional.

So both an industrial and regional policy combined to ensure that strategic industries survived and often thrived. Professor Cumbers points out that successful developed countries have retained their own steel-making sectors, including the Netherlands, Belgium and the USA.

Total output went up faster in the Old Industrial Regions of the UK, but employment growth was in the service sector rather than helping the march of the makers.

Cumbers also points to a weakness of the UK's dependence on inward investment - that when companies contract, foreign headquarters are more willing to sacrifice distant plants. The fate of Britain's steel industry currently rests on decisions made in corporate headquarters in Bangkok and Mumbai.

Strategic security

Recent decades show that the relative decline of manufacturing with the growth of the service sector is a widespread phenomenon that accompanies economic development.

Economic theory says you shouldn't need to make your steel locally if it can be more efficiently produced elsewhere and imported. Britain is a very rare example of a country that seems willing to put that theory to the test.

And given that it maintains a shipbuilding capacity on the Clyde to protect its strategic security interests - in being able to build warships for the Royal Navy - it is odd that it does not also insist on protection for the steel industry that supplies the Govan and Scotstoun yards.