Forties at 40

- Published

In 63 and a bit years, the Queen's had a hand in much of the British economy; opening factories, bridges and the Border railway, launching ships, asking why no-one foresaw the financial crash, and adding her royal warrant to Deeside suppliers of Balmoral's comestibles and household sundries.

But the event that took her to Aberdeen 40 years ago was perhaps the most significant economic event in her reign.

That was when she pressed the button that started the Forties pipeline, external flowing.

It wasn't the first oil brought ashore. That had been in June 1975, by tanker.

But the pipeline network was vital to making the North Sea viable.

Ramping up

It's the risk that the pipeline networks throughout the North Sea may no longer be viable at the current oil price that is one of the industry's big concerns about the next 40 years.

Sir Ian Wood, Aberdeen's foremost oilman, has said that his forecast of 15,000 job losses this year has turned out to be too optimistic.

The supply of oil worldwide has not fallen as much as expected at the start of this year. Indeed, recent investment has led to production ramping up, in British waters and elsewhere.

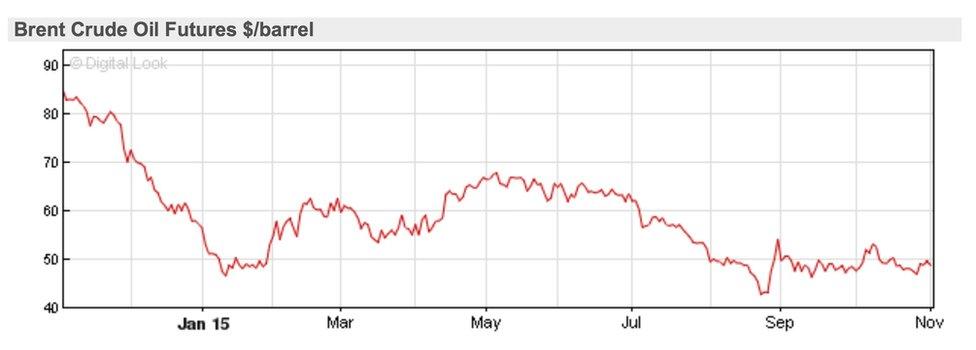

China's slowdown has contributed to weak demand. So the price of oil has failed to recover from the low point it hit in January. A barrel of Brent crude is currently trading around $50.

Not viable

Sir Ian Wood told the industry website EnergyVoice.com that he thinks the oil price might head back towards $75 in 2017, but he said of the UK industry: "At $50 or $55 a barrel, maybe a third to half of the fields are just not viable. The North Sea is having a very hard time. In 2016, there will inevitably be more job losses."

Companies that held on to staff in the hope of riding out the price downturn are now changing tack, preparing for a much longer downturn, and shedding staff.

Recent third quarter results from the US and European oil majors point to a drop of about 30% in investment spend between last year's intentions for 2016, and the plans now.

And it feeds down the supply chain. A leading player in North American fracking, Weir Group, has just announced from its Glasgow headquarters that 400 more jobs are going.

Windfall past

So there's not much celebration as the Forties turns 40. But as this is a significant milestone, here are three observations about the industry, from past, present and future.

Looking back, and looking from the UK across the North Sea to Norway, it's hard not to contrast the way in which the neighbours handled their windfall.

Norway has a humungous oil fund. Britain spent the windfall as it was brought onshore, and for various reasons, now has a humungous national debt.

That much is well known. But there's more to it than that, according to an interesting study by a young London consultancy, external, Crystol Energy.

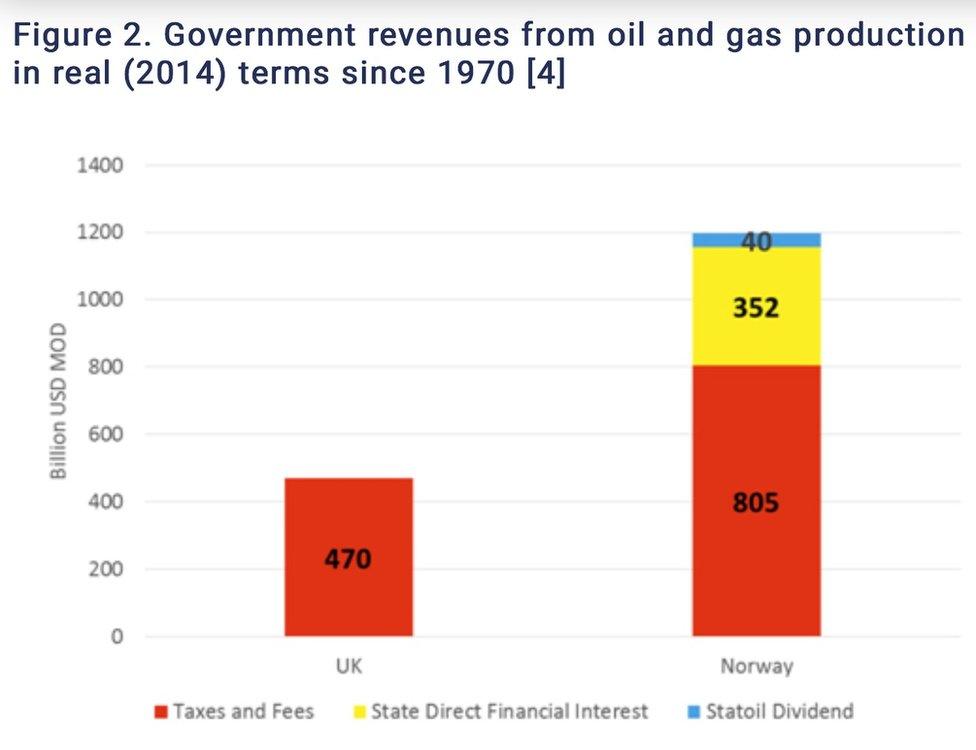

The two countries have extracted similar amounts of hydrocarbon - 43 billion barrels of oil or its gas equivalent for Britain, and 40 billion for Norway. But they've taken very different amounts of benefit from it.

Since 1971, Crystol reckons that the UK government has gained $470bn (at 2014 prices, or £305bn at the current exchange rate). Norway has pocketed $1197bn (£776bn).

Allowing for slightly different output, that means the UK got an average $11 per barrel, while Norway got $29.80. That's an astonishing gap.

Privatisation past

Why? Partly because Norway had a higher tax take on profits. But more important is that it benefited from the timing of when it extracted its oil and gas.

UK production peaked when prices were low, while Norwegian production peaked in 2004, when they were higher. Since 1971, the average barrel of Norwegian oil fetched $10 more than a British one (at 2014 prices).

Add to that Norway's larger and therefore more profitable offshore fields, and there was more profit on which to levy tax in Oslo.

Then there's the ownership factor. The Norwegian government took a substantial direct stake in its oil sector. The British government sold its stake in the early 1980s. At today's prices, it is reckoned it made £2.44bn for the privatisation sale.

Because the Norwegians had such a big equity stake, its government gained a further $9.80 per barrel in profits over the past four decades.

That required the Norwegian taxpayer to take on a sizeable investment risk in the 1970s and 1980s.

And you could argue that the UK option meant lower taxes over the decades, allowing individuals and companies to allocate their money more efficiently than government could do. But when you look at the outcomes, that doesn't look a very compelling argument.

Distressed present

A lesson from the present. Norway hasn't had it all their own way. One of its companies, Noreco, this week abandoned one of its investments in the UK North Sea, meaning its 20% stake in the Huntingdon field is shared between the other partners.

It had hired an agency to sell the stake, but there were no buyers. So it takes a £45m loss. A lack of buyers at any price is a clear signal of an industry in financial distress.

That's at the same time that plans to re-open the vast Ardersier fabrication yard, near Inverness, have been dashed. Its owner has called in administrators.

Much of the hope for the next wave of steel fabrication was in offshore wind farms, yet this week has seen approval for the first British floating wind farm. It's an investment by Statoil, the Norwegian government's energy giant. If that technology works, there won't be so much need for the steel jackets piled into the seabed.

Exploring for the future

A lesson about the future. For all the crisis in the industry this year, it continues to discover big new fields.

Wood Mackenzie, the Edinburgh-based energy consultancy, says finds around the world are in line with those last year at this stage, at around 10 billion barrels of oil or its gas equivalent.

This year's big finds are to be found around the coast of Africa and off South America.

In the UK offshore sector, exploration has been exceptionally rare, following poor recent results and a reputation for high costs.

The UK Government sought to stimulate activity with a £20m spend on seismic surveying of under-explored parts of the seabed.

This involves a large specialist ship blasting air pellets at the seabed from its hull. Astern, long trails of monitors pick up the patterns of the signals as they bounce back to the surface. From these, geological maps can be created.

The government contract was completed this week. So we now have public ownership and open access to a survey covering around 200,000 square kilometres, some of it in the trough near Rockall to the west and in the central North Sea.

It is a cheap alternative to tax breaks to incentivise exploration. And there are richer prospects for the oil majors to seek out around Africa, the Caribbean and Brazil.

It is only by such drilling that the UK industry, 40 years on from the first oil through the Forties pipeline, can hope to have domestic production in 2055.