Scotland's jobs stagnation

- Published

Is it only the trouble in the oil and gas sector that is weighing on the Scottish economy? Or do recent job figures suggest something else is going on?

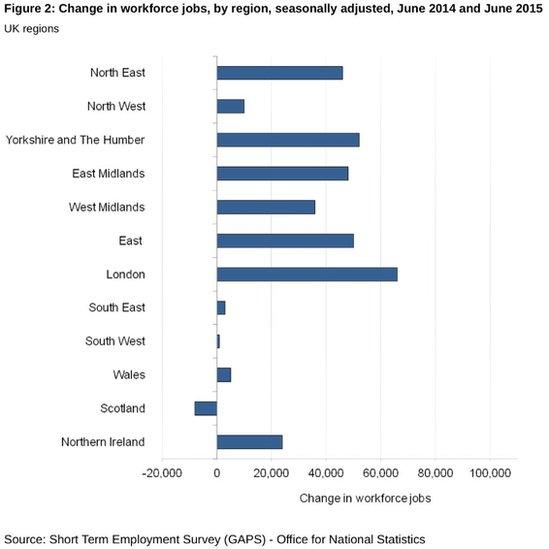

The data covering July to September repeats recent trends, of very strong job creation across most of the UK, but much weaker in Scotland.

If you take the 12 months to the third quarter of this year, the number of people in jobs across the UK was up 419,000. In Scotland, it was up 9,000.

At least that's heading in the right direction. The reverse side of the coin shows unemployment falling across the UK, to the lowest point since spring 2008. But it's been rising in Scotland.

The number seeking work across the UK over the year to the July-September quarter was down 210,000, but in Scotland it was up by 2,000.

Compared with spring of this year, unemployment was up 11,000. So whereas Scotland was doing at least as well as the UK average through most of the downturn years, it is now at 6% unemployment, while the UK is on 5.3%.

Only north-east England, Wales and London have higher unemployment rates.

London tends to have a high rate because of a bigger labour churn - that is, people leaving and starting jobs within the three-month period of the survey.

The so-called "northern powerhouse" policy is badly needed in north-east England, where unemployment remains highest in the UK, at 8.6%.

The most positive take on these figures is that Scotland's employment rate remains higher than the UK. At 74.1%, it's the same as in England.

The Scottish Government also points to marked improvements in youth employment, which it has made a priority.

Construction boost

But the STUC says the figures suggest Scotland's labour market is "basically stagnating".

Why? Well, it's hard to discern an explanation from the Scottish government as to why that might be.

It can take credit for the public spending boost to output in the construction industry, while services and production have been weak.

Ministers call for much slower cutting of the deficit than George Osborne plans.

But that doesn't explain why Scotland is diverging from the UK path, with slower growth and higher unemployment.

Growth priority

As an aside, it may turn out to be significant that the priority of growth is being put ahead of inequalities - or at least that Finance Secretary John Swinney has said that inequalities will be tackled through growth.

Announcing 16 December as the date for publication of his draft budget for 2016-17, he commented: "We have been clear as a government that we will tackle inequality through economic growth, and my budget will advance that vision."

What he has argued clearly in the past is that reduced inequality can help boost growth (it can, but doesn't necessarily), and that inequality and growth can be in tandem.

But this latest comment suggests the fruits of economic growth, in higher tax revenue, can be used to tackle inequality rather than the more radical option of re-distribution through tax rate and benefit changes. Some on the political left may be disappointed.

$48 per barrel

If we are to assume that the woes of the oil and gas industry are the explanation for Scotland's disappointing job and growth figures, the upside of lower energy prices should be that energy users have more money to spend and to invest. But that doesn't seem to be feeding through to a boost for retail spend or in business investment.

With Brent crude trading below $48 per barrel, it seems to be the downsides that Scotland is experiencing.

That is felt in communities across the country, where people work offshore or in the supply chain for offshore oil and gas.

The claimant count for Jobseekers Allowance is down in most Scottish constituencies in the year to October. The only six where it rose were in Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire.

Headwinds

There are other headwinds facing the Scottish economy, including the strength of sterling against the euro, which explains some of the current pain for exporting manufacturers. There are concerns about a global slowdown as China cools and emerging markets turn more uncertain. But those same challenges face the whole of the UK.

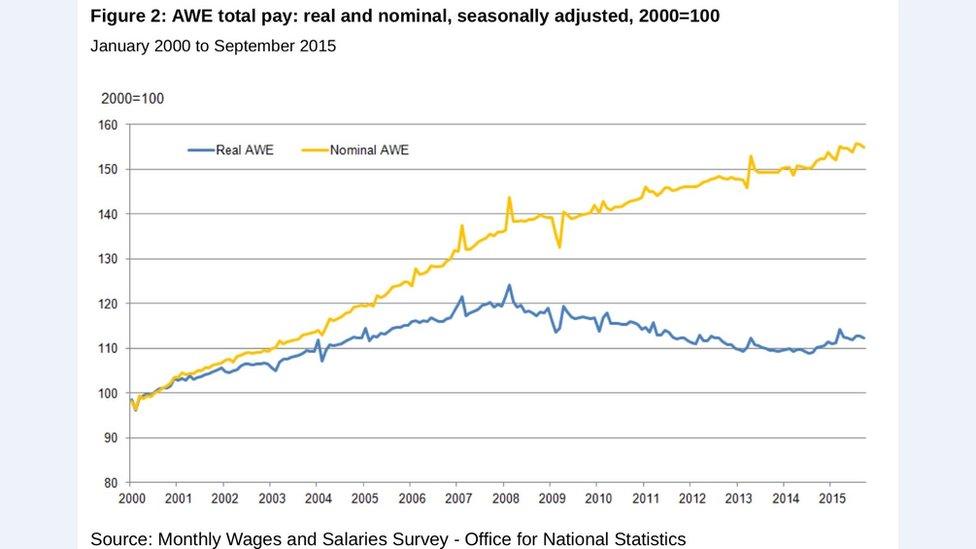

Viewed from London, these latest job figures offer another reason for interest rates to go up. The Bank of England can be relieved that the tighter jobs market doesn't seem to be inflating wages as fast as it might.

Average weekly earnings have risen in cash terms, but in real spending power, they are at the same level as 2005

The business lobby worries more about skills shortages, with some sectors - led by construction - seeing pay increases well above average.

When interest rates do go up - as they surely must one of these days - it will be judged to be necessary for the UK as a whole.

But it may be much less so for those parts struggling to get investment going again.

- Published11 November 2015