Osborne and Swinney: balancing the books

- Published

George Osborne's spending review has raised some interesting challenges for Holyrood

George Osborne says he aims to "fix the roof while the sun's shining". To help make the point, perhaps unwittingly, he's granted £5m to a refurb of the Burrell art gallery in Glasgow.

It has a very leaky roof, but this being November and the collection being in Glasgow, there's not much sun shining. Work is due to start early next year, lasting until 2019, at an estimated cost of £66m.

There are, of course, rather more significant Spending Review announcements on which to reflect. Here are some, as they affect Scotland.

Defrosting council tax

A lot of what the chancellor announces on such occasions is policy for England, or for England and Wales. There are financial consequences that feed through to the Barnett Formula block grant reaching Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. But there are also policy consequences.

Devolution is under way in England. The chancellor says English local councils could raise more if they feel it's needed to meet their social care costs.

John Swinney will be setting out his draft budget on 16 December

That raises the question of whether John Swinney, Scotland's financial secretary, will do something similar, when he sets out his draft budget on 16 December.

It seems more likely, facing an election next May, that he continues the freeze. However, facing some very tough budget decisions, councillors are wondering: for how much longer can the tax be frozen, if services suffer as a consequence?

Rates shake-up

There is a big shake-up afoot in business rates. The chancellor is handing the power to English councils to vary them, to compete in attracting businesses and to incentivise growth. John Swinney has done something similar.

But many in the business community say that this shake-up, and the end to the Uniform Business Rate, is the opportunity to go much further, in reforming a system which the Scottish Chambers of Commerce describe as "no longer fit for purpose".

Transactions slip

One advantage of the business rates system is that it continues to deliver a predictable flow of revenue - not far off £3bn per year in Scotland. The same can't be said of the replacement for Stamp Duty.

The Land and Buildings Transaction Tax has been a Holyrood tax since last spring. And the Office for Budget Responsibility reckons that it is falling far short of expectations.

In July, the OBR forecast £540m from the tax this year. It now looks like £142m less than that. Over the next five years, the shortfall averages £150m per year.

It may be that it is slowing up the number of transactions at the upper end of the market, due to a higher level of tax from £330,000 upwards.

Or it could be a temporary effect, bunching transactions on the cheaper side of the reform.

But for all the talk and legislation for tax powers at Holyrood, this is a reminder that revenue is volatile.

It can beat expectations, as George Osborne has just shown. Or it can leave a gap, which is what LBTT appears to be doing to Mr Swinney's financial planning.

Holiday homes

To help plug his deficit, one of Mr Osborne's ideas which the Scottish finance secretary might wish to consider is a higher rate of transaction tax - three percentage points higher - for those buying homes-to-let, or properties as second homes - though it won't apply in Scotland.

The buy-to-let phenomenon is not as hot a topic in Scotland as it is in London. Landlords in Scotland are already facing a legislative shift in their powers to evict tenants, and they see the Scottish government as making the private rental sector - though increasingly important to housing - an unattractive place to invest.

But then, there are parts of rural Scotland where there would be a warm welcome if second-home owners faced a higher hurdle when they buy.

Pulling levers

There is a much bigger lever that Mr Swinney can pull from next April. He'll have half of income tax under his control.

This isn't optional, as the tax power has been since 1999. The Scottish Parliament has to set a tax, and the barrier to altering it is much lower than it's been.

To avoid the spending squeeze implied by the Osborne spending review plans, it is estimated that the 10% tax would have to rise to 13%, with the higher rate of tax going up from 40% to 43%.

That said, the Scottish government is expected to keep the rate at the 10% level being inherited from the Treasury (that's in addition to the other 10% being levied by the chancellor).

It would be politically awkward to raise tax while fighting an election. Higher taxes tend to hurt growth.

And ministers have argued that they don't want to vary tax rates until they're able to achieve some redistribution - that is, taking more tax from the well-off.

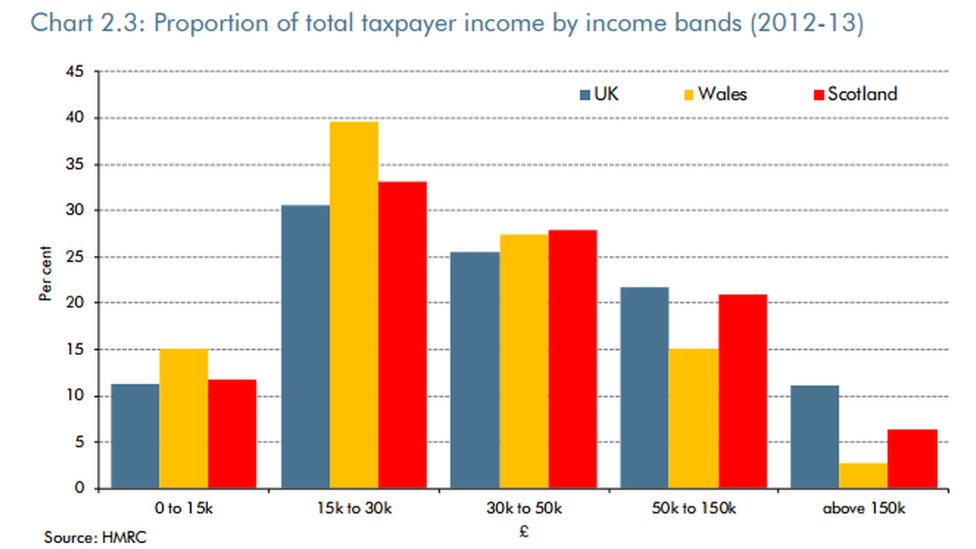

But here's an interesting thing highlighted by the OBR. It has looked at the pattern of tax contribution from different levels of earnings in different parts of Britain.

What it found is that Scotland has a higher share of its income tax from lower and middle earners than England. Wales is even more skewed towards dependence on lower earners.

As most of the tax changes over recent years have targeted higher earners - such as a higher rate of tax for those over £150,000, and changes to top earners' pension entitlements - the OBR suggests that the share of UK tax take from Scotland has been falling.

That will have consequences for the way in which income tax reform is eventually implemented at Holyrood.

Negative tax

On the subject of volatile taxes, they don't get more unpredictable than offshore oil and gas.

With prices and production down, investment write-offs and profits squeezed hard, the OBR has cut its estimates of what the Treasury can expect to get from offshore operators. And that followed a sharp cut at the July budget.

Petroleum Revenue Tax is consistently negative for the period of the spending review. That's as much as £700,000 that the Treasury will have to give back when companies file their corporate returns.

After factoring in corporation tax, it looks like £100m for each of the next four years, before rising slightly. This year, that's less than 1% of the £10.9bn tax take as recently as 2011-12.

To look at it another way, the past five years have brought in £30bn of tax revenue from offshore oil and gas. The next five years are now forecast to reap less than £1bn in taxes from beneath the seabed.

For those, like Mr Swinney, preparing a renewed case for Scottish independence, that's far from helpful.

- Published25 November 2015

- Published25 November 2015