Aviation takes off, destination unclear

- Published

It's time to give up on having to co-ordinate with London, and time to connect with the rest of the world directly.

That's not as political a message as it might sound. And it jars slightly with the symbolic message from the London Stock Exchange this morning, opened by Nicola Sturgeon as a sort of recognition of London's importance to the Scottish economy.

The message of direct links is not political but sound commercial sense, according to the boss of Edinburgh Airport.

He's reflecting on the changes in economics (cheap fuel) and aviation (long distances flown by mid-sized planes) that have allowed long-haul connections between Scotland's airports and the big hubs of continental Europe, the Middle East and North America.

The UK government's further delay in taking a decision about the right place in the south-east of England to build more runway capacity has been widely condemned as putting politics (the London mayoral election in May) ahead of the infrastructure that's necessary for the wider UK economy.

It doesn't align well with the Prime Minister's frequently used rhetoric about Britain being in a global race against those with big ambitions to take a bigger chunk of the world economy. Heathrow recently lost its long-held position as the world's busiest international airport, which is now in Dubai.

Inbound travellers

Yes, Heathrow is an important part of the south-east economy, but it's the hub by which much of the rest of the country connects with the world.

With the skies over Heathrow crowded, the issue of a third runway has long been on the agenda

Scotland and Northern Ireland have been more affected than most by the lack of capacity for short-haul flights feeding into the more lucrative long-haul ones at the big London hub.

For much of England, improved rail and roads have made it less important that travellers fly into Heathrow before flying out. At 400 miles-plus, or across the Irish Sea, Scotland and Northern Ireland still feel the need to fly, if they are to make those connections.

What is often forgotten - and yes, I've said it before - a lot of the UK depends on enticing inbound business and leisure travellers to head out of London. And if the flights are not there, or are not conveniently timed, or are not attractively priced, then they're not going to bother.

Even when precious landing slots were protected for a rival to British Airways to compete on the Heathrow links to both Edinburgh and Aberdeen (a regulator's requirement for allowing BA to take over BMI) Virgin couldn't make it stack up, and has walked away. Those slots have been lost.

Volatile fuel

These, however, are pretty good times for aviation. While other economic indicators are downbeat, the passenger numbers from Edinburgh and Glasgow airports keep rising, and they're adding up to be the strongest since the financial crash.

Edinburgh and Glasgow airports have experienced growth in 2015

These long-haul flights are one of the main reasons, while the low-fare airlines are packing in passengers to European destinations.

Investing in airlines has rarely looked a good bet. Profit margins are often unimpressive, whereas losses can be astonishing.

The industry has long had problematic union relations, it is vulnerable to volatile fuel prices, it's faced a series of disruptive business models, and travellers are fickle, depending on the latest terror or health scare.

But the fall in fuel prices over the past 18 months has made flying a lot more attractive, and boosted profits.

Earnings fly higher

Last week, IATA, the industry's global co-ordinator, set out its expectations of profits for next year. In 2014, total industry profits were just north of £11bn.

The forecast for 2015 last June was just under £20bn. It is now 10% higher. And the expectations of 2016 are for another 10% rise, to £24bn ($36.3bn). That translates to a staggering 3.8 billion passengers.

European airlines have been slower than others to benefit from the lower oil price, because they typically hedge 80 to 90% of their fuel. As forward contracts are completed, they are able to buy cheaper fuel, and to pass that on in lower fares and higher profits.

Thanks to Ryanair and other providers, cheap travel around Europe is now a viable option for many

Driven by Ryanair and other disrupters, European fares have become very competitive. So while the return on investment is much improved, profitability is still not great.

Per passenger, profit is reckoned to be around £6, while in North America, it is £14. Higher US interest rates going into the new year will put pressure on those figures, as those new aircraft have to be paid for somehow.

However, that market disruption, more competition and lower fuel costs help explain global passenger growth at 6.7% this year. It looks like being slightly stronger next year, says IATA. That helps make up for sluggish cargo growth, reflecting the poor state of global trade.

Climate change

But while IATA was announcing such growth, and Downing Street was stuck at the departure gate on the new London runway decision, there was something else going on that ought to have some bearing on all this.

In Paris, the climate change talks were heading towards the weekend's agreement.

Following agreement by 195 nations at the climate change summit in Paris, what next for the aviation industry?

If all those targets are to be met, then aviation is likely to have to play its part - if not contracting, then slowing the rate of growth.

In the Asia-Pacific region, rising prosperity is driving growth in aviation capacity, by 6% this year, rising to a forecast 8.4% next year.

In Europe, capacity is up nearly 4% this year, and is heading towards 6.2% growth next year, with Turkey as a major driver.

In North America, capacity is rising from 3.7% to 4.8% next year, on the strength of the US economy.

Green targets

Unlike profitability, capacity is directly linked to carbon emissions. And there are policy dilemmas here for governments, including those in London and Edinburgh.

If they are to hit those targets, aviation could be protected, on the grounds that it is economically important to continue its growth. But that would mean greater sacrifices in other parts of the economy.

The London runway non-decision is an unorthodox way of putting constraints on the industry's growth. The environmental argument at Heathrow has more to do with emissions from ground transport than aircraft.

Taxes or carbon trading look like a more sensible approach, but it has been very hard to find international agreement on such ideas.

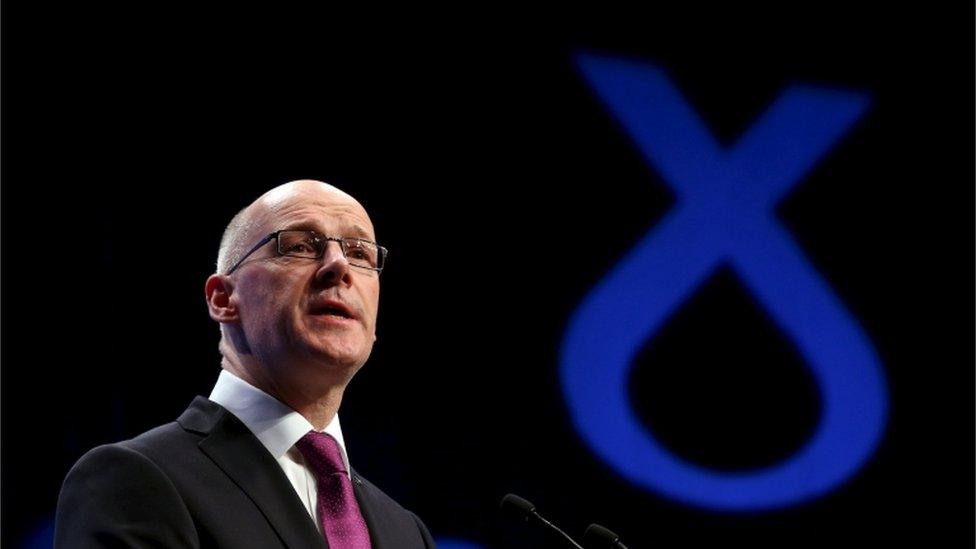

Deputy First Minister John Swinney will deliver the draft budget later this week

Without a common approach, the UK's high level of air passenger duty creates incentives for travellers to use airports elsewhere for long-haul, including Dublin, Amsterdam, Paris and Frankfurt.

The Scottish government wants to use new powers to cut the passenger duty, and has trouble explaining how that fits with its world-leading green targets.

Politics is about choices. We're told there are difficult ones due in this week's draft budget from John Swinney. The London runway decision is a choice between London politics and the wider UK economy. And many other governments will have strike a balance between greenery and growth if they are to hit these targets.

All that is before the Paris Agreement on climate change provides further momentum for the campaign to 'keep it in the ground'. It is clear the mainstream of the environmental movement is now heading in that direction.

However green governments aspire to be, it's hard to find any which are volunteering to plug and abandon their oil wells.

- Published13 December 2015

- Published13 December 2015

- Published15 October 2015

- Published11 December 2015

- Published12 October 2015