Second wind for UK oil and gas?

- Published

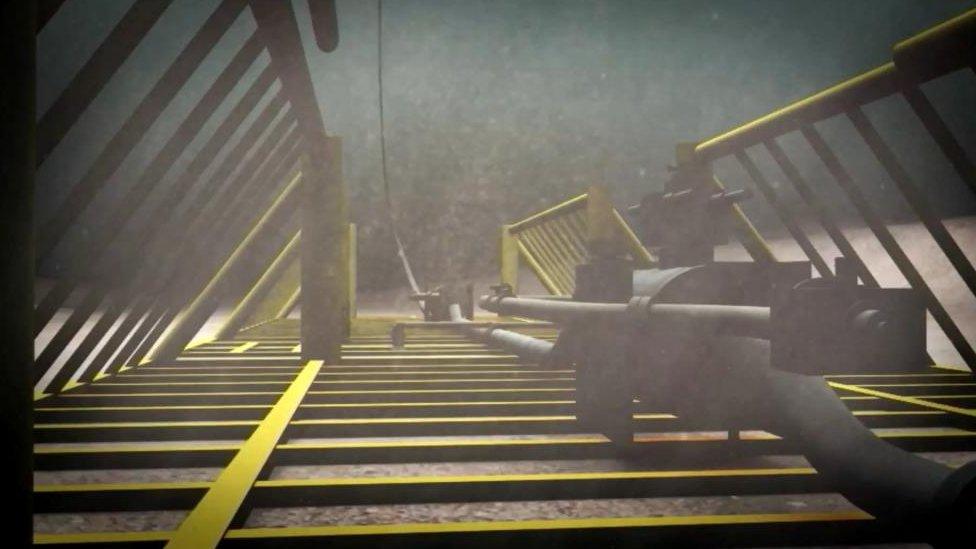

Two 18 inch pipelines have been laid to take the gas produced 90 miles to land

There's a second wind to Britain's oil and gas industry. And it's been in the pipeline for years.

Getting to "first gas" from the Laggan field has taken a long time. The Laggan field was discovered 30 years ago. Nearby Tormore, scheduled to come on stream later this year, was found nine years ago.

While oil fields have been developed and operated in deep water west of Shetland, including Foinaven and Schiehallion, gas production has presented much bigger challenges, both technical and financial.

But now that gas is flowing, the £3.5bn price tag for Laggan-Tormore should provide infrastructure for further gas development.

From those funds, a billion pounds worth of pipeline has been laid along the seabed, to which other projects can be attached.

The Department for Energy and Climate Change estimates that 17% of the UK's gas reserves could lie in the area, and they've been stranded until now.

High voltage power

A new processing plant has been built at Sullom Voe in Shetland, to remove impurities. And there is a further pipeline to link into the subsea network that takes gas to the Scottish mainland at landfall north of Aberdeen.

The project has pushed at the frontiers of sub-sea engineering. That part of the Atlantic brings some big swells and strong winds, and much of the work is only possible during summer months.

While some new oil platforms have been designed for remote control, normally operating without any people on board, Total has opted to place all its offshore equipment on the seabed. Each manifold weighs around 900 tonnes.

Pumping gas, at 600 metres below the surface of the Atlantic, involves a lot of pressure, currents and very cold water, which can cause the gas to condense and block the pipeline.

That's why there are not only two 18 inch pipelines to take the gas 90 miles to land, with concrete protection from fishing nets, but there's also a pipeline for anti-freeze.

Total battled with tough weather conditions to enable the plant to be built and start operating

One more line along the seabed is for fibre-optic communications of real-time electronic sensor and camera information, informing decisions at the Shetland control centre. Yet another is to supply high voltage power to the installation.

The pipeline south towards the Total network that connects with the Scottish mainland required numerous agreements with other companies on cross-over of their pipelines.

According to Total UK's new managing director, Elisabeth Proust, the project team battled with tougher weather conditions than expected. The civil works turned out to be far more difficult, expensive and time-consuming than in the plans.

A new power plant was required, following a failure to agree terms for sharing the one controlled by BP in the neighbouring oil terminal.

There were complex environmental requirements to protect the peat bog at Sullom Voe by storing it nearby, with monitoring to ensure its carbon content is stabilised. The project faced restrictions on pipe-laying near shore during the season for seal pups being born.

Petrofac, the large oilfield services company contracted to build the Shetland processing plant, will be relieved to pick up its tools and depart the site. Its chief executive described the experience as "deeply disappointing".

Operating costs

The overrun has cost it well over £200m, as it has scrambled to complete what started as a £500m contract.

At peak, there were 2,700 people working on the project in Shetland, requiring accommodation on berthed cruise liners and several floatels in Lerwick harbour, plus a large fleet of buses to transport them more than 20 miles to Sullom Voe, and back.

The company's usual sub-contracting model had to be abandoned as contractors failed to deliver. It complained of high labour costs, and clashed with worker unions on claims that productivity and disruption had slowed progress.

That work continued well into last year, although first gas had been scheduled for 2014. This month was the latest in a long series of target dates Total set.

So lessons will be learned. Madame Proust, a petroleum engineer who has held several senior roles within France's oil major, is emphatic that costs of operating in UK waters will have to come down.

Eighty people are being employed to run the subsea operations for Laggan-Tormore

Employing only 80 people to run the subsea operations for Laggan-Tormore, and doing so onshore, helps keep those costs down compared with conventional oil platforms.

But over the next 10 years, it is estimated that it will cost a further £690m to operate the fields. They have an estimated lifespan of 30 years, producing the gas equivalent of 99,000 oil barrels per day.

So, that ought to help reverse the steep declines in total UK offshore production over recent years, if only temporarily while other reserves deplete.

A further £1bn has been spent on developing nearby fields, also bearing the names of whiskies; Edradour and Glenlivet, scheduled to start producing gas during the next two years.

So this second wind looks significant. It results from an investment splurge of about £40bn, spent in a short period at the start of this decade, and helping to explain why costs inflated fast.

Some of that spending was on re-development of ageing fields, using new techniques for so-called Enhanced Oilfield Recovery.

The big projects were untapped fields where other novel techniques were being developed, such as Laggan-Tormore. Lerwick Harbour has seen much activity for further large newly-developing offshore fields. Clair Ridge is being developed by BP west of Shetland.

Will Total make a return?

Mariner, which Statoil of Norway is developing, has viscous or "heavy oil", which has presented other big challenges to drilling engineers, and can only now be exploited.

The investment boom was due to tail off after 2014. But it has fallen off a cliff, due to the fall in oil and gas prices.

Elisabeth Proust laughs wryly at the question of whether Laggan-Tormore would get the go-ahead now, suggesting the project might at least be "postponed a bit".

Will Total make a return on its investment at current gas prices? "We can, but it requires extremely good performance in production, and to be extremely strict on cost," she replies.

Those high costs are a big issue for investing in British waters, but she says this remains an attractive country because it has established working practices and a reliable, skilled supply chain. Plus, she says, "there is still prospectivity".

Indeed, there could still be very large oil and gas fields. But very low exploration activity recently, and even more its low success rate, mean that depleting reserves in old fields are nowhere close to being replaced.

The weather is blustery and unpredictable in these northern waters, but this second wind may be short lived.

- Published8 February 2016