Minding Scotland's research gap

- Published

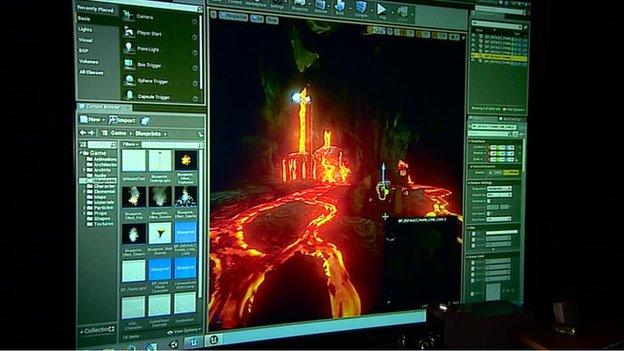

The future can be bright, if you log on, prepare for it, and keep innovating.

Scotland IS, the trade body that represents digital industries, reports today on a survey showing companies have recently been enjoying impressive growth in sales, exports and in jobs.

Some 84,000 people work in the digital business, says the organisation. And it's reckoned another 70,000 could be created within the next five years.

But these are often jobs that could be created elsewhere. And it's been forecast (in the US) that nearly two-thirds of jobs that will be filled by today's school pupils don't exist yet.

So preparing for the future requires imagination. And according to Scotland IS, it needs connectivity, skills, research and access to growth capital to ensure Scots can take advantage of global and domestic opportunities.

Connectivity

There are gaps in all of these. Broadband and mobile connectivity is one of the areas being emphasised in the Holyrood election campaign pitches to help economic growth (not that they have yet featured prominently).

Scottish education ought to provide an advantage in skills, though it faces very tough international competition to raise the quality of workforces, with vast quantities of technology graduates from emerging economies.

It is research that is a particularly big problem for Scotland - not in the quality of what's going on in universities, but in the lack of investment by businesses in Scotland. The position has become slightly less bad, according to the statistics issued this week by the Scottish government.

But that's from a very poor position, and it still leaves Scotland trailing its international competitors.

Tech hot spots

These figures cover 2014, and show that research and development by businesses reached £905m in Scotland. With nine more people employed in R&D in 2014 than in 2013, that's nearly 10,000.

Sounds impressive? Well, consider this. The spend per head on R&D in Scotland two years ago was £159. The UK figure was £309. In the east of England, where Cambridge is one of the technology hot spots, there are defence contractors, and a lot of Big Pharma at work, it is £703. More than two-fifths of the UK's business investment in R&D is in the east and south-east of England.

Only five companies account for nearly a third of Scottish R&D spending. More than half of it takes place in Edinburgh, Aberdeen (nearly five times higher than the Scottish average spend per head) and West Lothian.

Some 45% of business R&D carried out in Scotland is by businesses owned in the USA, far ahead of the 29% by Scottish-owned companies.

Growth has been significantly faster in Scotland than the rest of the UK in recent years

The retreat of manufacturing explains much of this story, yet it still accounts for more than half the R&D spend. Investment by other sectors has been volatile, and mostly disappointing. You may think that it doesn't matter so much to spend on research for product development in the service sector, but that would be to ignore the growing importance of fintech, or financial technology.

There has been significantly faster growth in Scotland than the UK as a whole since the start of this century. But in 2014, business R&D represented only 0.6% of national output. The UK figure was 1.09%.

And this is where its gets a lot more alarming, because the UK as a whole lags its economic competitors.

The share of British output in R&D is lower than the European Union average. It's half of the scale of commitment to be found in Sweden and Finland, where Nokia may have shrunk, but the innovating habit seems to have stuck.

Only Italy and Canada come close to Scotland's position, at the bottom of this international league table.

Growing Value

There have been numerous attempts over several decades to address this well-known problem. Obviously, they haven't had all that much success.

One of the current ones is an industry-academic group called the Growing Value Scotland Task Force.

It is compiling a report, due for publication next month. So far it has identified the problem in a similar way to its predecessors.

It cites figures that show Scotland contributed only 3.1% of business R&D to the UK total of £24.1bn in 2012, which is just over a third of its population share.

The interim report notes that the level of co-operation on innovation between businesses and universities in Scotland is much lower than for the rest of the UK, as is the capacity of business to absorb knowledge gained from research.

It raises questions of whether the strategy should be attracting big research firms, particularly those from the USA, or encouraging home-grown companies to think more in terms of innovation through research.

Mis-match

And if it's a question of public policy, which sectors? The unsnappily titled Growing Value task force looked at digital, financial, oil and gas and life science. It found businesses need to be clearer about their R&D needs and communicate them better to universities.

Universities were found to be constrained by competition between them. Or as it was grandly phrased: "The collaboration landscape is disaggregated".

There's a mis-match of the pace at which academic researchers move compared with the business need to get results soon.

The findings so far suggest more could be done on curriculum development and student placements to fit with business needs. There is the suggestion that oil and gas firms could be forced to invest in R&D, as in Brazil and Norway (though that may be the last thing they want to hear at the moment).

Business leaders admitted they could do more to welcome ideas from outside their firms. But they also observed that they innovate in ways which add ideas and continuous improvement and which don't count as fundamental R&D for the accountants and statisticians.

Academic researchers could be encouraged to work with colleagues in business schools to package industry-ready projects, the task force suggested. And why not have better incentives for academics to get rich in the process, or at least trouser some modest moola?

'Mission impossible'

But there's another possibility. Maybe universities are the wrong place to look, if Scotland is to grow its economy and prosperity with its brainpower and innovation. That's the provocative view of a St Andrews University academic, which was published this week.

Ross Brown, at the management school in Fife, says that the pressure on universities to take up the slack in business commitment to R&D, and to generate high-technology start-up companies, has "largely failed". Indeed, it may be "mission impossible".

"The strongly engrained view of universities as some kind of innovation panacea is deeply flawed," he says. "As occurred in the past when inward investment was seen as a 'silver bullet' for promoting economic development, university research commercialisation has been granted an equally exaggerated role in political and policy making circles. Universities are not quasi economic development agencies."

Why? Based on his research, Dr Brown has developed the view: "Most academics make poor entrepreneurs and often view public sector funding as a form of research grant income. Additionally, despite the high level of focus on stimulating university-industry linkages, most SMEs (small and medium-scale enterprises) do not view universities as suitable or appropriate partners when it comes to developing their innovative capabilities.

"Given the nature of the local economy with its very low levels of innovation capacity in SMEs, the remit conferred upon them is a mission impossible for Scottish universities. Part of this owes to the mismatch between the advanced nature of higher education research and the more routine technical needs of most SMEs."

Collegiate

Yes, he says, writing in Industry and Innovation journal, universities are important to the economy for providing skills to a graduate level, and to attracting research income, while creating the economic environment for successful cities.

But in future, "policy makers might wish to get other actors, especially within the small business community, more centrally involved in shaping how best to tackle the deep-seated problem of low levels of corporate R&D in Scotland.

"Arguably, support organisations such as Scottish Enterprise should work to connect SMEs to all sources of innovation, not just universities. Given their strong vocational focus, FE colleges may also potentially have a key role to play."

Putting colleges to the forefront of economic development, instead of universities? It's not too late to get that into a Holyrood party manifesto.

- Published1 April 2016