Bank of Braveheart: Britain's first currency union

- Published

This story may have a familiar ring to it - Scotland in a currency union with the rest of the UK, even though relations can be hostile. Really hostile.

Scots mint their own currency, but it becomes devalued in the eyes of traders in the City of London. So the currency union falls apart, and Scotland runs its own currency and affairs.

It does so for the next 200 years. That is, until James VI becomes James I of Great Britain, and 12 Scottish pennies are pegged to a single English penny.

Yes, we're talking medieval economics here - a much under-rated subject, and partly because the evidence base is very sketchy.

But it's worth knowing for the next time you get into an argument with a London cabbie who refuses to accept your Scottish banknote.

Metal detectors

The evidence that is available has been drawn together by a coin expert at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. Martin Allen's academic paper was presented last weekend at the conference of the Economic History Society.

With the help of a lot of metal detectors, he has unearthed some surprising findings, which might resonate a little with economics and politics seven centuries later.

The evidence is based, first, on archaeologists' finds of hoards of coins, allied to the exceptionally good production records of England's mints.

And very useful to establishing the bigger picture have been hordes of people wielding metal detectors since they became commonplace in the 1970s.

They have helped historians map where coins were hidden or dropped. From this trove of numismatic treasure, they can deduce how widespread coinage was, from different mints in different parts of the country.

Disunited kingdoms

England's currency was already used on parts of the continent, and would become one of the most trusted forms of European exchange in the Middle Ages. Less well known was its use across Wales, the Isle of Man, in Ireland and in Scotland.

Wales appears to have become fully integrated at least as far back as the Norman invasion of 1066, and that is the way it has stayed to this day.

Ireland had a fully convertible currency union with England's silver-based coins from 1208. Hoards suggest there was also some influx of Scottish groat coins.

Export of Irish coins was forbidden in 1534, while English coins still turned up in Ireland after that. Irish coinage continued until the early 19th century, pegged to English values.

Having itself been a disunited kingdom, Scots did not have their own coinage until David I invaded England, according to Martin Allen. The Scots king took control of Carlisle in 1136, gaining its mint, and subsequently setting up mints in Scotland.

If English coins were circulating in Scotland before then, this historian says there has not been much evidence of them being found. (Perhaps Scots were better at hiding them.)

Full integration into the sterling zone may have taken around a century. But from single coins found by people with metal detectors in Scotland over the past 40 years, coins minted between 1180 to 1250 were mostly English by a margin of 184 to 46.

Sporran change

What this history means is that the Wars of Independence were fought while the countries had a single currency. Yet it was without any Scottish influence on monetary policy in London.

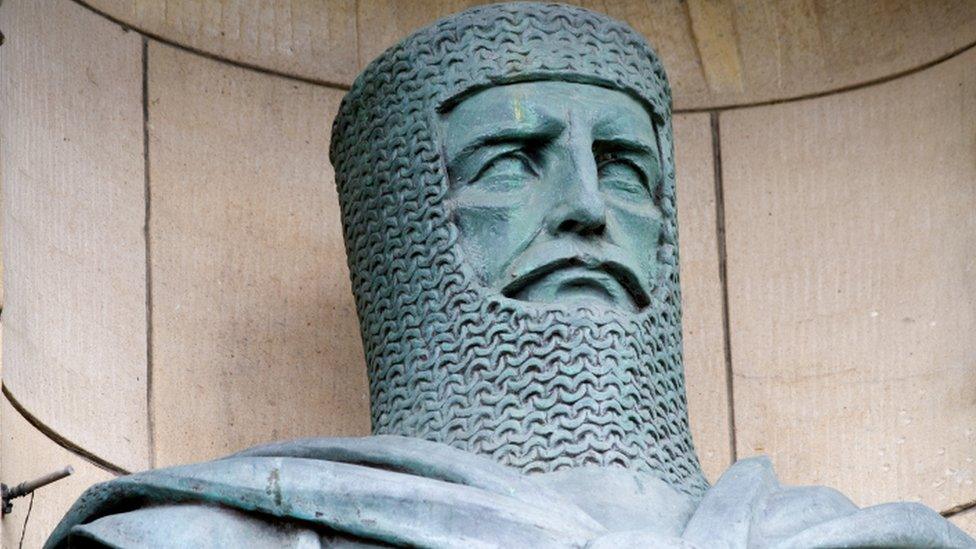

William Wallace and Robert the Bruce will have funded their wars in sterling.

Apparently, English soldiers brought quite a lot of their currency north, presumably knowing they could get change for an Anglo-minted coin. It is not recorded what they spent it on.

William Wallace will have funded his battles in sterling

Because credit was so undeveloped, and coins had their own gold and silver standard, it is possible to deduce the underlying health of the economy in the 13th century.

By those measures, the Scottish economy was growing quite healthily, and the Irish economy was much poorer.

By 1290, Martin Allen says there might have been around £125,000 of currency in circulation in Scotland, having seen growth of around 230% over the previous 40 years.

With a population of 800,000, it looks like currency per head was around 38 pennies, three times more than in Ireland, but 20 pennies less than in England and Wales.

The important point for medieval economic historians - and one that certainly resonates today - is to note that the sterling zone was not just about England and Wales. The southerners accounted for no more than 80% of the economy during the first sterling currency union.

Debased

Later in the 14th century, things went, as it were, south. In the later 1300s, Scottish coins were devalued, literally. This did not require watching screens of exchange rate spreads on global currency markets. It was about the silver content in coins being reduced.

The Scottish kings sought to bolster confidence in the exchange rate, but failed. 'The Debasement of 1393' was an ignominious event, and one which is unaccountably absent from school text books about Scottish history.

Its modern-day parallel was 16 September 1992, when sterling was ejected from the European Monetary System. It was an expensive fiasco, but by letting the pound devalue, it is seen by some now as re-starting Britain's economic independence.

So 1393 was the end of the road for Scotland's part in the medieval sterling zone. English coins still circulated in Scotland but, it seems, not that widely.

Later coin finds point to "bullion famines" when it was hard to get new supplies of gold and silver. One of them was when trade with Sudan seized up - a reminder that the economy of the Middle Ages was already globalised.

Cash was, at least, an instantly recognisable part of life in the British Isles through almost all of the last millennium. But for how much longer?

I have just been informed, by email, of a poll - carried out for Ingenico Group, "global leader in seamless payments" - which found that 71% of people in the payments industry think cash could have become obsolete in Britain within 10 years. A further YouGov poll suggests 43% of the public think the same.

Could this be a foretaste of "the debasement of 2020" - when the coin melts, the paper note is folded, and the only people continuing to say that "cash is king" are historians?