Where have all the jobs gone?

- Published

Brent crude has been flirting with the $50 mark, and the prospect of a further rise towards a sustainable level in the sixties dollar range.

The boss of Total, speaking to the BBC this week, gave a pithy insight into the market - that they used to think $100 per barrel was effectively a price floor, and now it feels more like there's a ceiling.

And yet neither is true, he added. The price goes up and down, no-one can be sure where and when.

While it stays under the $60 zone, there's a lot of adjustment still to go in the Scottish oil and gas sector, as we learned from the latest Aberdeen Chamber of Commerce survey.

It found nearly two-thirds of contractors reduced staffing in the past year. In the next year, 15% said they expected to boost hiring, but 30% said the cuts would go on.

Just over quarter of the sector's contractors are more confident about the year following the survey, and 50% less so.

But they're being resourceful. Even though the moratorium in Scotland may be made permanent, 70% expect to move into fracking and other unconventional drilling.

Some 61% anticipate being involved in renewable energy and 85% in decommissioning over the next five years.

'Unsettling' figures

The woes of the oil and gas sector help explain a lot about what's going wrong with the Scottish economy and jobs market.

The figures out this week were described as "unsettling" and "an amber light" by the Federation of Small Businesses. That's something of an understatement.

The unemployment rate is higher - 6.2% to the UK rate of 5.1%. Wales is at 4.8%, so it's not all about the rich south-east.

The only nation or English region to have a higher rate than Scotland is the English north-east, with 7.9% unemployment.

About 61% of the oil and gas sector's contractors anticipate being involved in renewable energy over the next five years

The gap, which was a permanent feature for the Scottish economy last century, has not been this wide since 2004, the point at which the Scottish economy began an unprecedented period of convergence with the UK's, if not bettering it.

But it's the job creation figures that are more striking. In the first quarter of this year, compared with the last quarter of 2015, the Labour Market Survey suggests there were about 97,000 new jobs across England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

In the same period, Scotland lost 53,000 jobs.

Since the first quarter of last year, the rest of the UK has seen employment growth of 454,000. If Scotland were performing like the rest of the UK, it should have nearly 10% of those. Instead, it lost 45,000 jobs over the year.

The Resolution Foundation think tank puts it in the context of the downturn. Last autumn, Scotland at last reached the employment rate before the crash, back in 2008. It has now fallen below it again.

Economically inactive

Unemployment went up by less than 2,000 during the year to January-March. That was while the UK total fell by 139,000.

So the other factor explains a lot - the rise in the economically inactive, people, aged 16 to 64, who tell the Labour Force Surveyors that they are not available for work.

Among those aged under 65, the numbers looking after family, in full-time education and with long-term ill-health tend to stay roughly stable. The proportion of retirees aged under 65 has been falling.

That doesn't explain why Scotland has seen the rise in economic inactivity - up 43,000 in the year, while in the UK, it has fallen 116,000.

Perhaps it has to do with gender. Women's unemployment has fallen in the year to January-March, by nearly 11,000. Unemployment among men has risen by slightly more than 11,000.

The contrast on economic inactivity is even more striking. The number of men in that category is down 3,000.

The number of women who were not in the labour market was down by 47,000 (some of these numbers are rounded, and don't necessarily tally for that reason. There may also be some explanation that's being missed because the sampling of the Labour Force Survey at Scottish level is less robust than the UK research).

Discouraged workers

We're not given details that break down Scotland's inactivity, or at least none that are reliable. But across the UK, you can get an idea of how 8.9 million people in that category break down.

A quarter are in education, just as many are looking after family or home, and nearly a quarter are long-term sick.

Although they were inactive by not having looked for work in the previous four weeks, and not being available for it in the two weeks after the survey, a different quarter said they would like a job.

The element that might be expected to rise with an economic downturn is "discouraged workers". They were a lot more numerous when welfare benefits made "scunnered-so-can't-work" a relatively attractive option.

When the Labour Force Survey began in 1993, there were 167,000 such people across the UK. But in the most recent survey, there were only 27,000 of them - less than 0.1% of the workforce.

So there's still no clear explanation why the Scots are diverging so much on inactivity.

About time

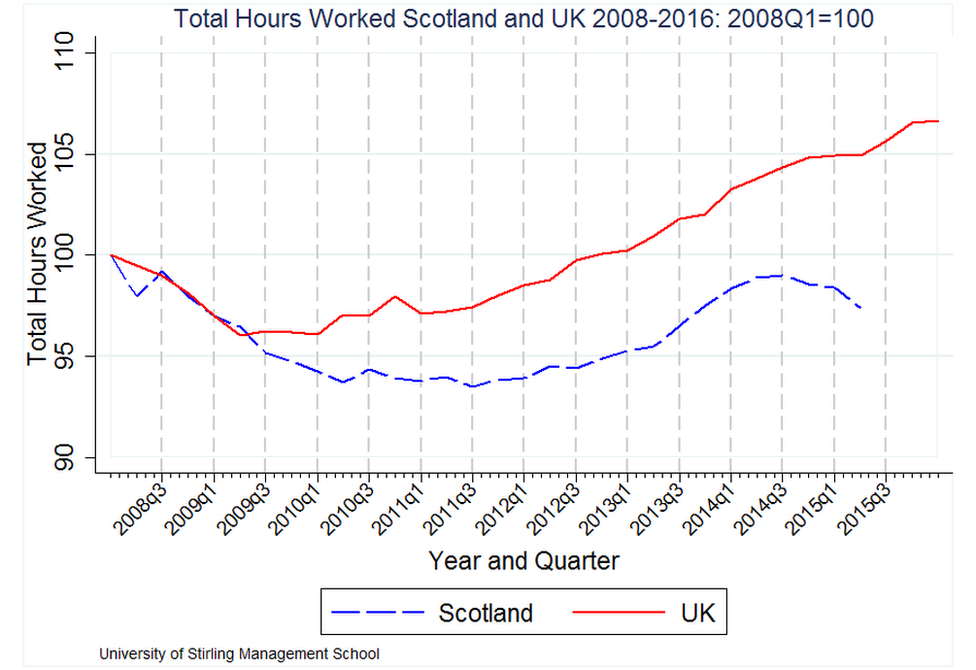

But there is a part of the labour market survey that suggests the growing divergence is not just about job numbers, but about the number of hours worked.

It showed that UK hours worked have risen during 2015, when compared with the whole of 2014. But Scotland was one part of the country with the lowest average hours worked.

During the year, it was among the biggest fallers in average hours worked and weekly hours worked, by more than 2% in a year.

That may not sound much, but aggregated across the whole economy, it's significant. And as they have figured out at the economics department of Stirling University, the hours work gap has widened with slower Scottish growth rates, now turned into a Scottish decline in hours worked.

If the number of hours worked were falling while productivity - output per hour - were rising, then that could be just fine. Workers could be producing at least as much and have more leisure time.

Instead, poor productivity continues to be a big challenge, and a priority for the re-elected SNP government. Put together with falling hours worked and falling employment, it's not a healthy combination.

So looking to the inner workings of the Scottish economy, there may be even more unsettling figures than the headline loss of jobs.

- Published19 May 2016

- Published17 May 2016