Place and space: A new plan for planning

- Published

How much do you know or care about your local planning office? If you're like me, you'll get an occasional note that a neighbour wishes to alter an extension, and they're consulting under the terms of the appropriate Act, section this and sub-section that.

And as I'm not a property developer, that's about it. As with actuaries, undertakers and taxidermists, one aims to leave them undisturbed to do whatever it is they have to do, unless you're left with no option.

Yet the influence of the planners can be seen all around us. They get to say where housing goes and what it looks like, what is zoned for commercial development, and where advertisers can put their billboards. Obviously, but importantly, they also say where you can't put these things.

Planners are the people who choose the routes of controversial roads, such as the Aberdeen and Inverness ring roads. They say what can and cannot go in sensitive World Heritage Sites in central Edinburgh. They deal with the pressure from developers such as Donald Trump, to drive a golf course across sand dunes on the Aberdeenshire coast.

They choose where wind turbines can spoil the view or kill birds in flight. They judge what it is appropriate for councils to expect of developers in terms of "planning gain" - the requirement to build roads and a school or two, in exchange for the right to build a housing estate.

There are dozens of consents in the planners' arsenal - building warrants, alcohol licences, conservation areas, a habitat or species licence, listed buildings, marine licences, permits to pollute, road construction, traffic regulation and road closure, forestry projects and permission to cut down a tree.

And on the subject of felling trees, this is an industry that generates a lot of paperwork. It's been slow to adopt new technology, and shuffles files around slowly. Sometimes very slowly. In July last year, nearly 1,900 applications were more than a year old, and one was aged a vintage 32 years.

Bureaucracy does not seem to be a by-product of the planning process: to this untrained eye, generating paperwork is actually the point of it.

Planners are seen as regulators, who stop things from happening, and who ensure there is order in the way our cities, towns, villages and rural landscape appear.

Enabled and empowered

But it doesn't have to be that way. They could enforce the rules (and some say they should do that better) but also be enablers. That's according to report commissioned by the Scottish government and published with a notable lack of fanfare.

Crawford Beveridge, who has been given big chairing tasks before - reviewing public spending, atop Scottish Enterprise, and the Council of Economic Advisers - was commissioned to lead a three-person team, with a remit to look at the way the planning system works, and more important, how it doesn't.

That was last autumn, as pre-election pressures built up over the shortfall in housing construction, and as businesses large and small voiced frustration at the blockages and delays to investment. Planning fees had gone up 26% in two years, but delays were a constraint on business and economic growth, as planning department budgets had been cut 20% in five years.

With this Beveridge report on ministers' desks, a new administration now has the space to make some significant reforms. Angela Constance has taken on planning as part of her communities, equality and welfare portfolio, with Kevin Stewart installed as her deputy on planning.

'Fundamental rethink'

The big legislative reform was 10 years ago. This new review reflects on ways in which it has helped, as well as its creation of new problems. It does so with a lot of planners' verbiage. But if you hack through the undergrowth of frameworks, consultations and plans about plans, there are some significant proposals as well as some eye-catching ones.

Without wishing to repeal the 2006 legislation or to take the plans out of planning, there is a call for a "fundamental rethink of the system as a whole".

The document's title gives a good clue as to what is intended: "Empowering Planning, to deliver great places". The focus is on trying to get the outcome right, and worrying less about the process, which is odd when the report is so full of discussion about process.

On the system itself, there is a warning that it has to build trust from the communities affected by planning decisions. And that doesn't mean more consultations.

"The multiplicity of plans in the system is leading to consultation overload, and the evidence suggests there is limited buy-in from communities, developers and other partners."

The evidence also points to planning authorities being "mired in the process of producing plans on time", which can be "overly comprehensive", leaving inadequate resources to follow through in actually supporting development.

This has become more complex still since the City and Region Deals started - driven by Whitehall, part-funded through Holyrood, and driving a coach and horses through council boundaries and existing plans.

Effective land

Some offered the commissioners the view that housing is so important that it has to be a national priority and part of the national planning framework. Others said housing already receives too much attention.

"The one point of consensus is that the way in which we plan for housing needs to change," said Team Beveridge.

Suggestions were put forward to the commissioners for doubling the release of "effective" housing land and outsourcing of planning.

There is a big gap between the sites identified for new housing and the number of completed homes. In 2014-15, there were around 40,000 units approved, but only 17,400 completed, most of them private. Ten years before, there were 28,500 houses finished.

One of the problems identified is that housing supply is failing to match changing needs, for living with disabilities, for instance, or for elderly people. The market has shifted significantly to the private rented sector. It is recommended that areas zoned for residential developments should include buy-to-rent blocks, with their tenanted status permanently preserved.

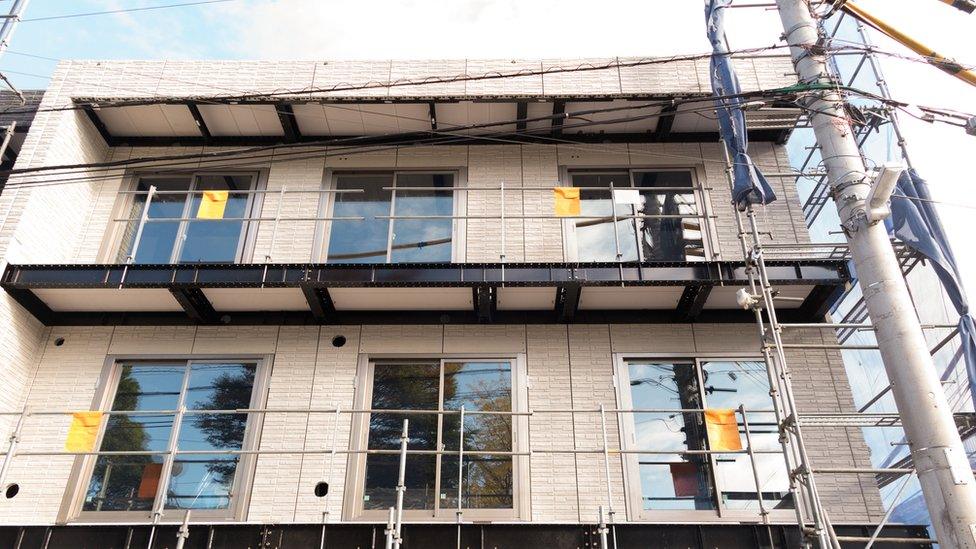

"Place making, housing quality, tenures and alternative delivery options [for instance, the pre-fabrication of house kits off-site] should play a much bigger role in planning for housing," says the report.

Planning gain, planning loss

There's a proposal for a national fund, perhaps a national infrastructure agency, to pump prime development, instead of relying on individual councils, with tightly constrained budgets, to build the infrastructure necessary for development - long before any council treasurer sees the consequent business rates uplift.

Allied to that should be a retreat from over-reliance on the "planning gain" or Section 75 requirements on developers. Too many of them are unrealistic and becoming obstacles to development and investment rather than facilitators.

Fees face a hefty hike, if Crawford Beveridge and his commissioners are to be heeded. But to reduce costs, it is suggested that councils share specialist knowledge of, for instance, wind farm planning regulations, and consents for various utilities be combined.

Ministers in St Andrew's House will want to pursue the renewed pressure to get councils working more closely together. There is also a strand of this report that fits with the Scottish government's new drive to push power down from councils to communities. Neither Nicola Sturgeon nor her ministers have explained in much detail what that means.

But in the case of planning, this report suggests it could mean a significant power for community councillors to draw up local plans, with which they can then influence the eventual outcome.

And as these buildings are designed to last a good few decades yet, it is suggested that school pupils should be co-opted into the cause of designing their future homes, towns and cities.

- Published1 June 2016