Business and Brexit: whatever next?

- Published

Has business been crying wolf? Heavily weighted to the Remain side, the voices of business Britain and corporate Caledonia raised a lot of serious concerns about the economic consequences of Brexit.

They lost the vote. And now, they're telling us they can cope with the upheaval that's being thrown at them.

That's because they have to. With markets taking a hit, as predicted with a Brexit vote, businesses are keen to reassure customers, staff and shareholders that they're on top of things. They're used to change. And they're keen also to emphasise that nothing needs to change immediately.

That's apart from the value of sterling, which has plummeted. For exporters, that means a price drop as they sell, which should be good news - at least while they retain their current access to to foreign markets.

For those that require imports - and many businesses buy foreign raw materials and unfinished goods - a fall against the dollar means their costs go up.

That's true of consumers too. And it seems expectations may have adjusted already. A colleague filming at a Glasgow street market on Friday morning interviewed a fruit trader who said every one of his customers had asked if he would be putting up his prices.

That increase in costs goes for fuel too, and anything else denominated in dollars. Although the price of a barrel of Brent crude has dropped, the counter-effect of the sterling fall is that fuel costs can be expected to rise.

Having reassured people that most matter to them, businesses are seeking next to get reassurance from governments and the Bank of England. The statement from governor Mark Carney was carefully crafted to provide just that.

While markets got a shock, and some traders will have been badly burned, the central banker was effectively saying: 'this is what we thought would happen if the majority was for 'leave' - we were ready for it'. It was a mild form of 'we told you so'. There may be more of that to follow.

Those sectors in Scotland most entangled with international trade, or which look to government regulation, include financial services, energy, food and drink and tourism.

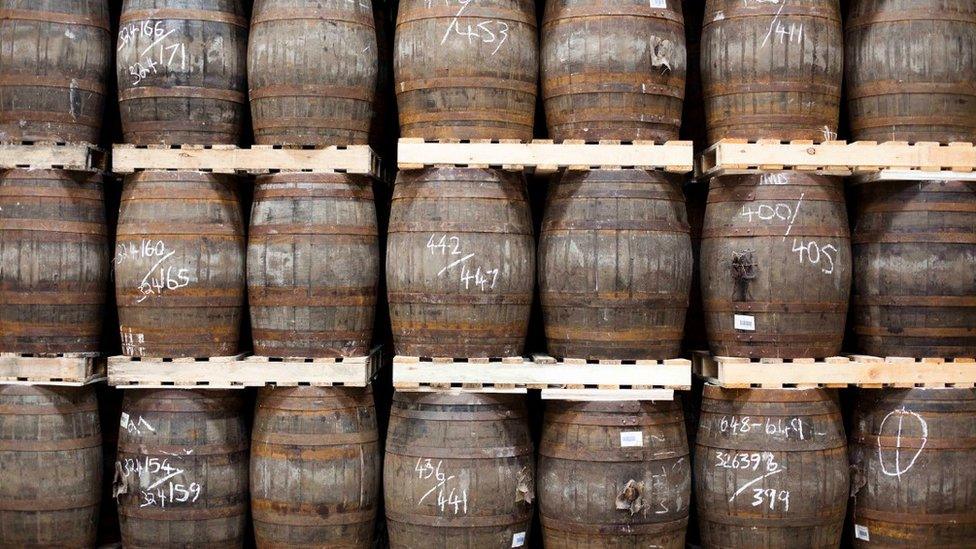

The Scotch Whisky Association, covering quarter of Scotland's exports, is significant for pointing out that exports into the EU are only part of its concerns.

It has counted on 50-plus trade deals with other countries outside the EU, negotiated through Brussels. It now faces uncertainty about them. And it needs to lobby Whitehall to ensure that its interests are taken into account with any future trade deals being struck.

Across those trading, regulated sectors, businesses now want to know:

* What is the timetable for change? Some companies and sectors are relieved that Brexiteers seem to be in no rush to make the break. Others are alarmed that the uncertainty could be prolonged. Some manage both relief and alarm at the same time.

* How and when will the law change as it affects trading contracts, and possibly also employment contracts? There are lawyers and accountants who could do well out of the change ahead.

* There is an expectation that leaving Europe will reduce regulation, or red tape. If it is to be met, where and when will that happen?

* How are companies to plan on their recruitment strategy when they can't tell who will be allowed to work in Britain? For some, in hospitality or agriculture, their entire business model has just been upended.

* What is the cost to the Scottish economy of another independence referendum campaign, and yet more uncertainty that brings?

Uncertainty equates to a lack of confidence. And that is bad news for new investment, for banks' risk assessments of creditor customers, for consumer confidence, and for recruitment.

So while businesses might look like they have been crying wolf, with their initial statements of calm reassurance, it is further down the road when they consider investment options that the damage to the economy is more likely to be felt.

Indyref2 too?

Much of bigger business in Scotland was reluctant to get involved in the independence referendum in 2014, at least until a 'yes' vote became a real possibility.

If they want to influence the next one, they will have to be aware that a lot of voters are not to be swayed by the threat to their economic interests. The democratic arguments in the European referendum seem to have outweighed the economic evidence.

But if Nicola Sturgeon is to press ahead with an independence referendum in the next two years, as she seems to want to do, she faces hurdles that weren't there before:

* An economy suffering from Brexit uncertainty, and probably slowing up next year.

* The prospect of border controls between England and Scotland for people and goods - not because of Scotland's constitutional choice, but England's. The Tweed could become a frontier of the European Union.

* The currency question, which was a weak spot of the last independence campaign, is no closer to being answered more persuasively. If anything, it has now become more complex.

* Scotland's fiscal position has weakened significantly since the drop in the oil price wiped out tax revenue completely. That price fall began as the 2014 independence referendum reached its climax. The Institute of Fiscal Studies now expects a further squeeze on the public finances as growth slows, meaning either higher tax, lower spending or more borrowing.

There is one big shift in favour of the independence case. Whereas it was previously seen as the risky option, that now looks like the course on which English and Welsh voters have set the UK.

In other words, the argument that an independent Scotland would be a dangerous step into the unknown is less effective when southern voters have chosen to launch the whole of the UK into the unknown.

New dawn

When the dawn broke on a truly historic day - Friday 24th June 2016 - it revealed the aftermath of a constitutional, political and, potentially, an economic earthquake.

Picking through the political debris will take some time. The area remains dangerous for the risk of further collapsing careers.

On the constitution, until the dust settles, it's hard to think of a single question to which the answer is clear.

And as for the economic consequences, Brexiteers argued they would be positive. There was only one group of economists that modelled that happening, Economists for Brexit. It will be interesting to find out if they got it right.

But it may take some time. Even the pro-Leave economists reckoned there would be a short-term hit to the economy, as it adjusts to a shift in trading relationships.

Other economists forecast output growing more slowly over the next few years, taking Gross Domestic Product to between 2% and 6% below the position it might otherwise reach within the EU.

If they're right, that would be the price of taking back democratic control.

- Published24 June 2016

- Published24 June 2016