Brexit and Consequences

- Published

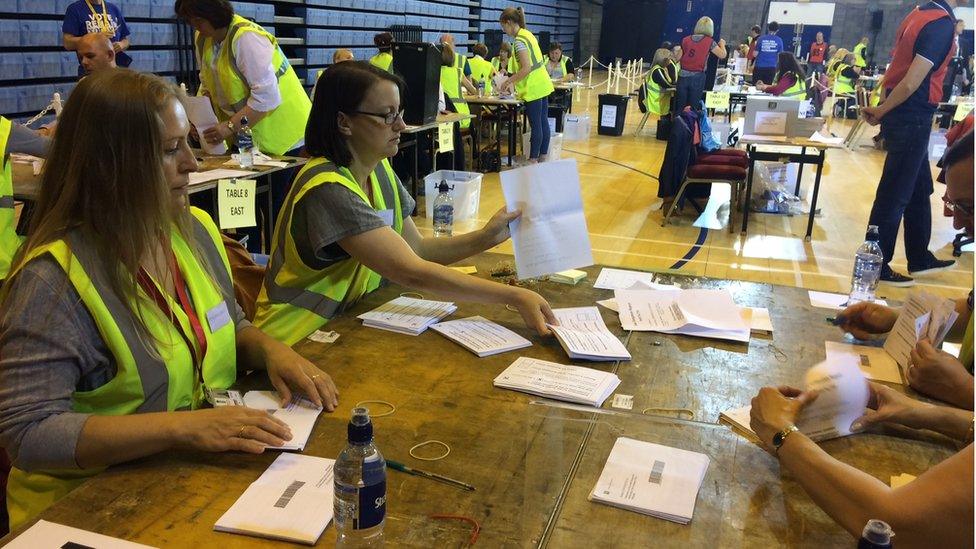

Quickly established as the dominant explanation for Thursday's referendum vote on European Union membership: the "leave" voters were largely from parts of the country and communities which feel left out of prosperity elsewhere.

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn says they feel abandoned, left behind and ignored, often with low-wage, insecure jobs - symbolised by a Sports Direct warehouse on the site of a former coalmine.

The message for eight years, fuelled through the budget decisions taken by the UK government, has been that the people who caused the financial crash have not paid the price. Ordinary Joe has had to do so.

Well, two days in, and it seems the bankers are now paying the price. Moody's credit rating agency has warned that it could downgrade Britain's rating. It's on "negative watch", which is a prelude to a cut.

The agency is waiting to see how the politicians react. The longer the uncertainty continues about the conditions of Britain's exit, the more it will hit business and consumer confidence, and the more growth will be hit.

From the continent, and the other 27 members, the message is clear: Allez-y. Get on with it.

They don't want uncertainty hanging over them. They seem ready to teach Britain a lesson in negotiating which will serve as a warning to others who think they might withdraw from the disciplines and costs of membership of their club.

No rush

In London, however, the Prime Minister is going by October. Ahead of then, he lacks authority to do much talking to EU partners. The Tories who led the Leave campaign aren't in a rush either.

If the markets continue to judge their delay as costly to growth, the signal might be clear that they need to respond to the pacier approach of the EU leaders.

While Moody's has issued its warning, Fitch is likely to do so on Monday, and Standard & Poor some time late on Monday at the earliest. The chief ratings officer of S&P told the Financial Times the UK's triple-A rating is now untenable.

Meanwhile, the repercussions are becoming clearer as European politicians have their say. The Dutch chairman of the Eurozone finance ministers group has said there will be a "price" to be paid, in less access to EU markets for UK financial service companies. He thinks Amsterdam and Frankfurt will pick up business. Financiers in Paris will also want to do so.

A member of the governing board of the European Central Bank has said the UK may lose its "EU passporting".

That is the ability to operate in any member country without having to set up separate business entities in each one. That's a significant saving.

Migration

It's suggested by this ECB bigwig that it would be different if Britain joins the European Economic Area (EEA), along with non-EU Norway. But the condition for that is that the UK accepts the EEA rules. And that means open border migration.

Influencing these rules has been one reason for having someone at the top table. Lord Jonathan Hill has been the UK appointee as a member of the commission (he's a former adviser to David Cameron). His portfolio has been financial services and, unofficially, managing relations around the referendum.

As a commissioner, he is not there to bat for Britain. That's what the Chancellor or other Whitehall ministers do in the Council of Ministers. But being in the Commission is an opportunity to keep a watching brief for issues that might be, let's say, problematic for one's sponsoring government.

For that reason, the financial services brief was a useful one for a Brit to have, just as the trade commissioner's post was for Lord Peter Mandelson.

But Lord Hill has quit, a Latvian is now overseeing the further integration of the financial services market, and will be influential in deciding what happens about that "passporting".

One of Scotland's MEPs, Ian Duncan, a Conservative, has also resigned from a committee chairman's post in Brussels where he was able to influence further developments in the Emissions Trading Scheme. While he stays on the committee, for now, he says the convener should be someone who will still be in post for the rest of the European Parliament's term.

Bankers

The banks on Friday took some of the biggest hits to their share price, following the Brexit vote. Lloyds Banking Group was down 21%, RBS and Barclays by 18%. Standard Life was down 17% and Aberdeen Asset Management by 11%.

That may delight those who felt the financiers and fat cats failed to pay a penalty for the crash and subsequent austerity.

But with it comes a warning from UBS Wealth Management, among others, that the second half of this year is likely to see no growth at all in the UK economy.

It says the fall in sterling will import inflation, and with stagnation, that puts the UK into "stagflation". That's not a good place to be.

It warns that interest rates look likely to face a further cut to zero, and if that still doesn't work, there may be a need for further money creation, or quantitative easing.

In addition, they warn that lower growth means bigger deficit problems than expected. With bigger deficits, there would be higher debt, and with lower credit rating, the cost of servicing that debt would go up.

And so it goes on. Financiers may sustain a wallop to their wallets, if economic slowdown means their bonuses are slashed. But it seems unlikely that they'll suffer the worst of the consequences.

Inflation alone takes a higher toll on the poorest. According to the Institute for Public Policy Research, a 2.3% increase in consumer price inflation can be expected to raise costs for the poorest 10% of households by 3.3%, and the most affluent 10% by 1.6%.

And that's before the impact on investment, jobs, pensions and public services. In other words, the highest price is paid by those who already feel abandoned and left behind.

- Published24 June 2016

- Published24 June 2016